...behind the cantilevered design was to avoid a column that would block a view of the Capitol, to the east.

The backbone of the stair is a series of eight, moment-connected bent steel box girders, 2.5 ft wide and 14 in. deep. The box girder continues 16 ft into the building, at each of four landings. The bent column is supported at its base on an 18-in.-deep, 12 x 14-ft reinforced concrete pad. The bent column supports one end of four stacked pedestrian bridges, 40 ft long and 12 ft wide, that link sections one and two.

| + click to enlarge |

Turner Construction |

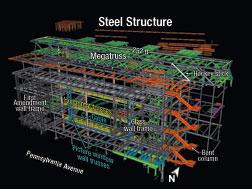

The 252-ft-long, 39-ft-wide and 16-ft-deep megatruss, a hollow box that forms levels six to seven in section two, is not as dramatic looking as the grand stair, but it was much trickier to fabricate and erect. The megatruss consists of two prefabricated trusses with expressed web members, offset about 2 ft from the top and bottom chords, outside the box. The offset allowed the architect to hide the chords behind cladding and free the expressed webs of large bolts and plates, making them look cleaner and lighter.

The megatruss creates more column-free space in the exhibit areas above the atrium, as well as spans the atrium. Up to two floors of the museum are suspended from the megatruss via steel hangers. Bottom chords brace elevator towers.

Near the east end, each truss sits on an expressed steel column, 123 ft tall and 10.5-in. wide, braced at every floor. Near the west end, trusses land on two concrete shear wall towers, slightly offset. The clear span between supports is 148 ft. On the east, the megatruss cantilevers 48 ft; on the west, 36 ft.

| + click to enlarge |

Turner Construction |

LERA Megatruss called the "craziest" part of the project, but bent column stair (below, left) looks more dramatic. Crane assembly needed 21 approvals.

|

Webs are a series of plate assemblies that resemble hockey sticks. Each stick’s 8-ft-long tail, in line with truss chords, helps transfer loads to the truss and keep the connection clean, says LERA. Hockey sticks are connected to each other by sliding a two-pronged end of one over a single plate of the other, at its elbow. Each stick is pin-connected to the chord through a 2-ft-wide plate—the distance to the chord—that is 8 ft long—the distance along the chord.

Workers from Clark Foundation, Bethesda, Md., started Newseum foundations in May 2004. Once at grade, Turner started section four first and had workers “back out” of the hemmed-in site to avoid painting themselves into a corner, says McIntire. Also, the section-three frame was needed to brace the megatruss during erection.

During the more-complicated work, from May 2005 until last March, LERA had a surveillance engineer on site to troubleshoot, answer questions and offer insight to the contractor, especially regarding interfaces between steel and concrete systems.

LERA |

McIntire calls the megatruss the “craziest thing we did” on the project. The large member sizes prompted steel contractor Canam/Structal to build a special assembly table, jig and fixtures at its Quebec City, Canada, fabrication plant. “Larger-than-normal truss members required very complicated fabrication tolerance calculations,” says Jacques Renaud, Canam’s project manager.

Truss prefabrication took two months, starting in October 2005. Canam made mock-ups for the expressed plate-to-plate welds. The design team made monthly visits to check accuracy. Because of the complexity of the truss, inspection was substantial due to the need to cumulatively measure chord distances and depths, says Renaud.

At the site, there was no room for truss section assembly. It really did not matter because each truss was too heavy to be lifted as a single piece, says Canam. The only alternative was mid-air splices.

Truss erection was so elaborate that Derr Steel Erection Co., Euless, Texas, started preparing nine months in advance. “The trickiest thing about these trusses is the eccentricity” from the hockey sticks, which are in a different plane from the chords, says Michael Kissane, a Canam onsite project manager. The hockey sticks threw the truss off balance, making it tend to lean over during erection, explains Kissane.

Shoring towers were not simple because the grade slab could not support them. The solution was to continue the towers down to the mat, through slab openings and a series of heavy structural frames. “LERA was worried about the concrete,” says James S. Kennedy, Derr’s senior engineer. “Every time I wanted to land lateral or gravity loads, to guy the truss or move the crane, they got really serious.”

Truss fit-up was difficult. McIntire says the engineer asked Derr to erect to 3⁄8-in. tolerance in any direction. “Derr said they couldn’t make it,” he says. “In most cases, we made 1⁄2 in.,” he adds.

In several locations, the camber was not exactly what it was supposed to be. “One splice at the very end took us a long time” and required jacking about an inch to get the correct camber, says Kennedy.

Turner Construction Engineers used steel to frame open spaces.

|

Steel erection began with the elevator tower frames below the future location of the megatruss, near its columns. Before megatruss erection could begin, the core towers had to be built to the underside of the trusses. After the shoring towers were installed, crews erected the freestanding columns. They were also temporarily braced to the concrete structure.

Steel erection began last Jan. 4. Mainly using a 300-ton crawler crane with a 100-ft main boom and a 70-ft luffing jib, workers erected the west half of the megatruss first, beginning with the first two sections of the north truss and followed by the first two sections of the south truss. Still moving west to east, crews then erected the final two sections of the north truss, followed by one section of the south truss. Infill members followed. Shoring remained until crews had erected the structure in section one, which braces the columns. Falsework came out March 31.

The truss will continue to deflect until the hanging floors and other construction is complete. But “all deflections to date are reasonable,” says LERA’s Sesil.

Because of the Newseum’s mission, the job for most of the building team has extra significance. “This building has to rise into the top 1% of anything I...have been responsible for in 45 years,” says Polshek.

LERA |  LERA |

| Exhibits include WTC antenna, left, still in storage and Berlin Wall guard tower installed early. | |

That resonates in a more direct way for LERA, a successor firm to the original design engineer for the WTC and the WTC’s building engineer until its destruction on Sept. 11, 2001. LERA engineer Richard Garlock helped find the piece, to be installed in May, in the ruins of Ground Zero. “Having the antenna display is important to us at LERA,” says Douglas P. Gonzalez, LERA’s Newseum project manager. “Many of us climbed that antenna tower to do inspections.”

Newseum president, Peter S. Pritchard, thinks there is something important about the museum for all Americans, whether or not they have a direct connection to the project, an artifact or both. “This is the museum for the ages,” he says. “The value of a free press and independent media is more important than ever, especially since most Americans take the First Amendment for granted.”

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment