...dust and materials from moisture damage. The building will be flushed with outside air prior to occupancy in April.

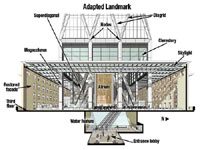

Turners Borland calls the base-building work "the first most challenging aspect" of a very challenging job. "The lower six floors account for 40% of the cost of the core and shell," he says.

Workers from LJC Dismantling Corp., Elmont, N.Y., kicked off a 32-month construction schedule in June 2003, with a multistage "surgical" demolition. Crews left the landmarks perimeter interior bay to help support the facade until new wall framing and third and seventh floor framing were erected.

|

| Exacting Placement. Diagrid erection (above) was slow, but much easier and faster than the base, which included the superdiagonals (right). (Photo above courtesy of Cives Steel Co.) |

In March 2004, workers from Cornell & Co., Woodbury, N.J., began steel erection. Thanks to the tight interface between the diagrid and the unitized curtain wall panels, "there was lots of opportunity but no room for error during steel fabrication and erection," says Totten.

|

It wasnt just the tower that was demanding. Cives spent months developing skylight frame connections that would satisfy the high design load to resist blast and yet meet aesthetics. In many locations, bolted connections were hidden inside the frames steel tubes.

The ends of megacolumns and diagrid columns were milled to less than 1/16 in. Measuring tapes only go down to 1/16 in. "This job was off the charts," says Totten, admitting that it was not profitable.

| +Enlarge | |

| |

| (Rendering courtesy of the Hearst Corporation) | |

Connections were developed to allow tenth-floor framing to be perfectly level and at the correct elevation so the diagrid above would interface with the curtain wall. Cives had to mill the diagrid node plates on all sides, instead of two, because a 10-in.-thick plate can actually measure 10 3/4 in. Surveyors frequently checked the x, y, z coordinates for elevation and plumbness, and maintained diagrid nodes to within 1/2 in. of the theoretical.

Cornell broke the building into two sections, one below and the other above the diagrid. "It took four months to get to the tenth floor," says Kevin Ducey, Cornells project manager.

The third floor became a platform for construction of megacolumns and superdiagonals. Superdiagonals, too heavy to ship in one piece, were assembled and welded on site. Two cranes picked each one.

The significant challenge at the tenth floor was the installation, on two falsework towers, of the beam supporting the superdiagonals. Compared with the lower levels, the diagrid was like production work, says Ducey. But because it was "very carefully" stick built, it took longer. Cornell built a floor every four days, instead of the more typical three.

|  |

| Sharp. Curtain-wall panel (above) for base of bird beak included stainless steel cladding as well as glass. (Photo left courtesy of Cives Steel Co.; right courtesy of Permasteelisa Cladding Technologies) | |

Because of the tight interface between the diagrid and the curtain wall, "we ended up buying the steel and the curtain wall roughly at the same time," says Bruce Phillips, manager for Hearsts local developer, Tishman Speyer. Curtain-wall bidders had to develop conceptual plans.

The curtain-wall supplier provided the window panels and the stainless steel cladding for the diagrid and other expressed framing. Every unitized glass panel is independent to absorb the buildings movement, according to Carlo Eisner de Eisenhof, senior project manager for Permasteelisa Cladding Technologies, Windsor, Conn. Of 3,200 glass panels, 625 are "special." Many of these are in the birds beak. Thirty-six of the largest panels, 15 ft tall and 12 ft wide, required a special frame for shipping at an angle.

The curtain-wall system included 600 brackets welded to diagrid steel at Cives plant. That reduced the depth of the panel by 4 to 5 in., allowing Permasteelisa to fit one extra panel in each shipping crate.

To make sure brackets were properly located, steel-detailer Mountain Enterprises, Sharpsburg, Md., shared its 3D model with Permasteelisa. "We coordinated so that anchors would not run into bolt heads," says Totten.

For the curtain wall, Permasteelisa did three visual mockups, four performance mockups and a blast test. It ranks the Hearst Building as its second-most difficult job and most expensive, at $126 per sq ft.

For Hearst, which is trying to attract and retain talent at its communications empire, the effort is likely worth the investment.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment