A federal appeals court’s decision has taken a step toward lifting a state ban on out-of-state water sales, opening a way for a proposed $3-billion project to pipe water from Oklahoma to Texas. The appeals court accepted a north Texas water district’s argument that Oklahoma’s ban could constitute illegal restraint of interstate commerce.

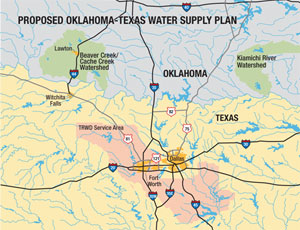

The Tarrant Regional Water District, a Fort Worth-based utility serving 1.6 million people in 11 counties, is seeking permits for 460,000 acre-ft of water per year. The supply is needed to accommodate the 4.3 million people expected to live in the district’s service area by 2060, says Wayne Owen, planning manager.

Two western Oklahoma watersheds, Cache Creek and Beaver Creek, would contribute 150,000 acre-ft annually. The Kiamichi River would be tapped for 310,000 acre-ft more.

In January 2007, the district sued the Oklahoma Water Resources Board and the Oklahoma Water Conservation Storage Commission, challenging a 2001 ban on selling Oklahoma water out of state. The latest decision, by the 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, in Denver, is the latest ruling favoring Tarrant’s case.

While the legal struggle plays out, early conceptual engineering is proceeding. Each intake would be located on the waterways a few miles north of the Red River, marking the states’ boundaries. Water becomes too saline once flow enters the Red River, Owen says.

Pumping stations would feed two pipelines. A 120-in. pipeline would run about 60 miles to Lake Bridgeport, northwest of Fort Worth, which is one of the district’s reservoirs. From there, it can flow by gravity to the rest of the system.

The eastern pipeline would likely consist of a single 144-in. pipe or a pair of 120-in. to 132-in. pipes, says Dan Buhman, president of Buhman Associates, the Coppell, Texas, water-resources firm leading conceptual engineering.

This second pipeline is to connect to systems run by one of the other two major Dallas-Fort Worth water utilities at an undetermined location on the eastern side of the metropolitan area, Buhman says. The other two water suppliers, the city of Dallas and the North Texas Municipal Water District, are partners with the Tarrant district, which is the lead agency. Both pipelines will be buried and likely pass underground for the handful of river crossings required, Buhman says.

Each of the large pumping stations at the river intakes will likely be in the range of 600 million to 900 million gallons per day, Buhman says. In addition, one or two booster stations will move water over intervening ridgelines.

Revenue bonds backed by the Tarrant district’s contracts to supply its wholesale customers—the cities of Fort Worth, Arlington and Mansfield as well as the Trinity River Authority—will fund the estimated $3-billion project, Owen says. “We have an unconditional obligation to provide their supply, and [our customers] have an obligation to pay,” he says.

No decisions have been made on routing, bidding or a construction schedule, although the district has set a deadline of 2010 to begin design and construction. The district will explore building new reservoirs and pipelines in Texas if legal issues halting the Texas-Oklahoma pipeline aren’t settled by then, says Owen.

“Once they have that resolved, design and construction will move forward at a quick pace,” Owen says.

The request for permits to pipe water from three Oklahoma watersheds to the fast-growing Dallas-Fort Worth area was opposed by some Oklahomans on grounds that the state might need the water during a drought. The Tarrant district sued in U.S. District Court for the Western District of Oklahoma, which ruled in October 2007 the matter involved interstate commerce, and allowed the lawsuit to proceed. Oklahoma appealed that ruling and lost. Now the case returns to district court in Oklahoma, where it will be heard in late 2009.

Previous attempts to move water from Oklahoma have not been successful. Although Oklahoma has sufficient water for a population several times its number of current residents, state residents have opposed such projects. One unsuccessful effort in the 1990s led to laws and policies that formed the present moratorium on water sales out of state.

Opponents may be shifting their tack, advising that the state take the district up on an offer to buy the water. They argue that if the permits were granted, water would be given away without any compensation other than cost of the permits.

The water district hasn’t set a specific price on its offer to buy the water but is waiting on Oklahoma to set a price. Meanwhile, it’s pursuing legal remedies. Oklahoma is seeking to maintain its moratorium while a study of its water supply is completed.

The appeals court’s ruling may be narrowly interpreted by others. Cautioning that he has not read the decision, Peter R. Johnson, program director of Chicago-based Council of Great Lakes Governors, says, “I would be shocked if it had any impact on us.” The Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Basin Water Resources Compact, which received final approval in October when President Bush signed a joint resolution of Congress, prohibits deliveries of Great Lakes water to customers outside its watershed.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment