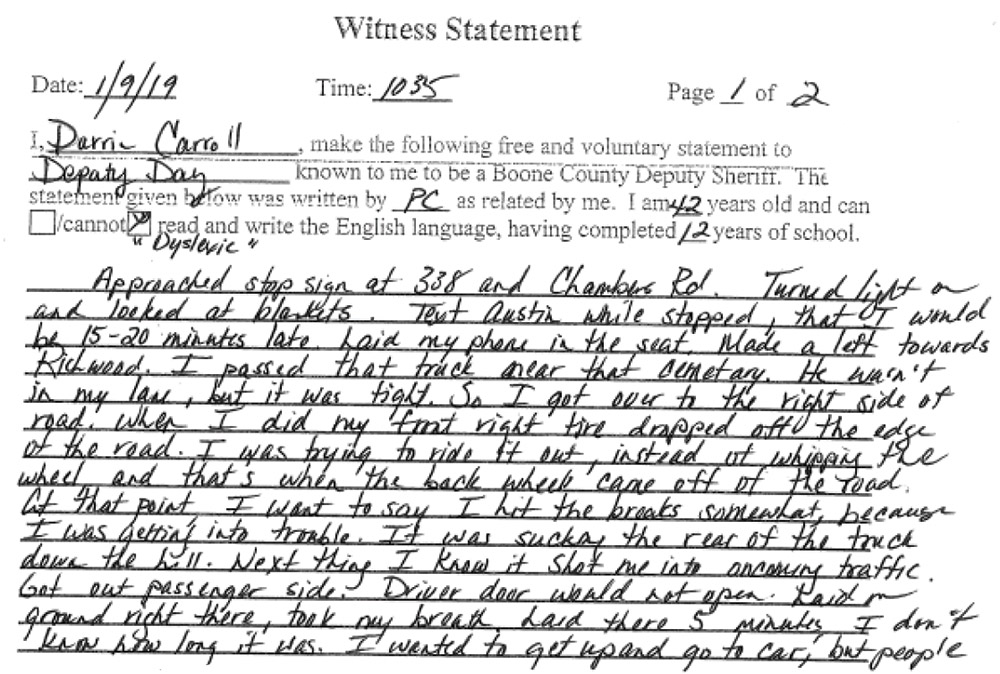

*Click the image to see a larger version of the witness statement

Darrin Carroll was running a little late for work. At about 7:20 a.m. on a cold January morning in 2019, the sun had not yet shown its face in northern Kentucky. Carroll, who had just reassured his employer that he was on his way, steered his red 2003 Chevrolet flatbed truck east along Richwood Road, State Route 338, in Boone County, Ky., not far from Cincinnati. It’s a typical rural two-lane ribbon of blacktop, and the straight section Carroll was driving along recently had been smoothed with an inch and a quarter of fresh asphalt over the existing surface. He pushed his unloaded eight-ton truck to about 54 mph, 9 mph higher than the speed limit.

Amy Skiba, a 45-year-old retired school counselor, was driving her Honda Accord west that morning, the opposite direction, taking two of her three children, 12-year-old twins, to school.

The cars were several hundred feet apart when Carroll saw a truck coming in the opposite direction close to the center line and he naturally went to the right, he said in a deposition taken last April. His right-side tires then suddenly dropped down onto the grass and soil fringing the asphalt. Carroll, his foot off the accelerator but not on the brake, did what other drivers instinctively do under the same circumstances—steered to the left to regain the road. At that point, it was “game over,” in Carroll’s words.

Podcast: Richard Korman on "The Verdict" story

“When the rear tires dropped, it just felt like it started dragging me further off the road, and then the truck just felt like it come [sic] up in the air, turned, and went straight across the road,” he said in the deposition. Carroll’s truck hit the front left corner of Skiba’s Accord, colliding with the energy of a 90-to-100 mph impact. After a brief moment, Skiba, who was gravely injured, fell unconscious while one of her terrified children, sprayed with glass and other fragments, reached for her cell phone. They dialed their 17-year-old brother, who was further back driving down the same road. When he arrived, he was the first person to see what had happened.

Skiba was later pronounced dead at the scene.

Do All Asphalt Edge-Drop Solutions Work Under All Conditions?

Image courtesy Commonwealth of Kentucky court files

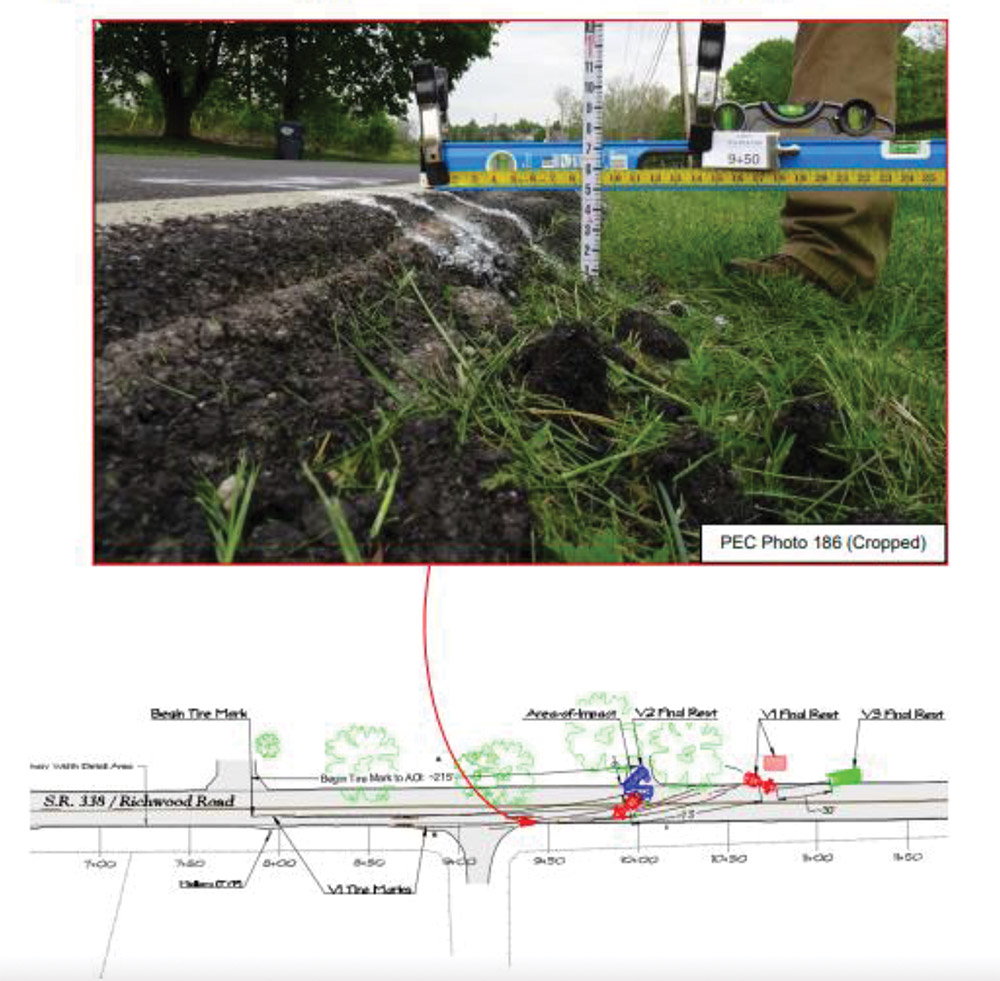

*Click on the image for greater detail

The conditions that contributed to the tragic crash that killed Amy Skiba are a well-known road departure hazard: a driver whose right-side tires have fallen off the asphalt surface is unable to easily regain the road, often scraping tire sides on the asphalt, and then oversteering into oncoming traffic (see photo and drawing).

*Click the image for greater detail

In testimony during the Godwin et al. v. Eaton Asphalt Paving, state project engineer Anthony Griggs stated that although he allowed Eaton Asphalt Paving to skip milling the existing asphalt surface before repaving, he expected a wedge treatment to be used to create a 30° safety edge that helps motorists who drift off to get back on.

But Eaton Asphalt Paving said it was regularly excused from creating a safety edge where shoulder conditions made it ineffective. Federal Highway Administration guidance says safety edges have been successfully built over crushed stone and in-situ soil, but “like any pavement, better performance may be expected with a better base to provide support.” A Nebraska study concluded that soil reinforcements may be needed, and California limits where and how safety edges are done.

Exactly why Carroll drove off the road isn’t clear. Experts and police suggested—based on interviews with Carroll and toxicology tests of his blood—some possible combination of fatigue, rushing, inattention and drug use caused the crash. The blood tests showed that Carroll, who police said told them he had been up late, had trace amounts of methamphetamine in his blood, possibly too low to affect his behavior. His blood also contained a prescription drug he was taking at the time. Carroll had twice previously been arrested for driving under the influence. The police investigation of the accident seemed to point the finger of blame at him.

Five weeks after the accident, when one of the lawyers retained by the children and their father went out to inspect the scene of the tragedy, the lawyer noticed an overturned vehicle near the same spot. That started him thinking about the road itself. When the attorneys filed their first amended complaint in state court in Boone County, they cast a wide net—naming Carroll, various employees of the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet, and Eaton Asphalt Paving Co., based in Walton, Ky., along with its parent company, Cincinnati-based John R. Jurgensen Co., which operates numerous construction related companies.

In nuclear verdicts, “the damages are noneconomic typically and can be grossly disproportionate to the damages in the case.”

- Walter J. Adams Jr., Berkley Alliance Managers

Eventually, the children’s lawyers emphasized the difference in level between the asphalt road and soil and grass that bordered it (there was no paved shoulder), ranging from 2.5 in. to 6.5 in. in the relevant eastbound section, and how that difference affected Carroll’s ill-fated attempt to get back in the lane.

Edge-drop, as it’s called in asphalt construction, would play a major role in the picture painted by those attorneys in a negligence case first filed in state court in March 2019 and later known as Alton G. Godwin et al. v. Eaton Asphalt Paving Co. Godwin is the children’s father and guardian. Taking advantage of natural jury sympathy for the children’s horrific experience and loss, court records show their attorneys methodically—before and during the trial—shifted blame away from Darrin Carroll and instead portrayed Eaton Asphalt Paving as a greedy corporation that risked the lives of motorists to pocket a bigger profit. It worked. A jury last July awarded the children $24 million in damages and another $50 million in punitive damages.

Liability Insurance Rates Climb

As construction fights its way through a period of material price inflation, another less-mentioned cost that has risen steadily for two years through the pandemic is liability insurance. In talking about how they see construction liability, insurers cite the unpredictable losses from emotionally driven jury damage verdicts of $10 million or more against designers and contractors. The industry calls them nuclear verdicts.

Walter J. Adams Jr., vice president of Berkley Alliance Managers, which provides claims services for insurer Berkley Construction Professional, says that despite the pandemic, an increasing number of lawsuits head toward court, with complainants either seeking unreasonably high levels of compensation or ending with juries awarding irrationally high payouts. Defendants in some cases are ordered to pay tens to hundreds of millions of dollars, says Adams.

“The amounts,” he says, are generally “based on how a jury feels about the situation and how wrong they feel the party was.” In such verdicts, Adams adds, “the damages are noneconomic typically and can be grossly disproportionate to damages in the case.”

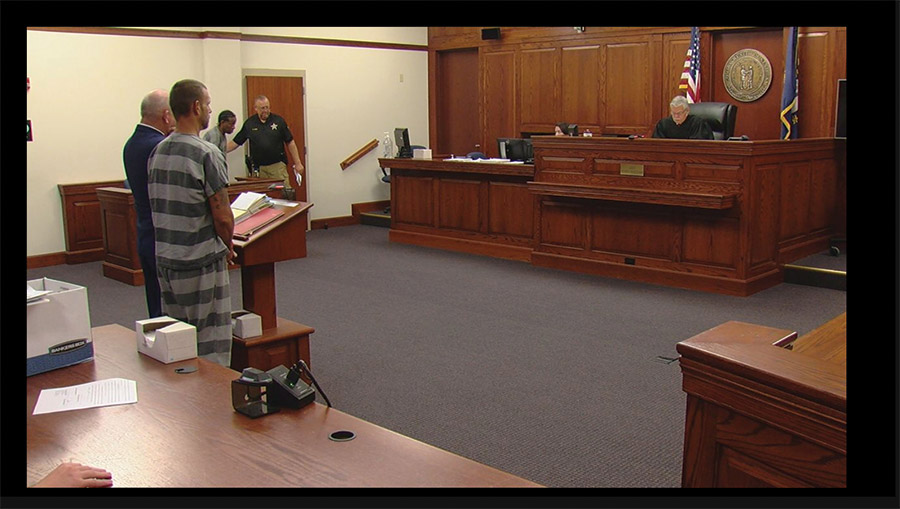

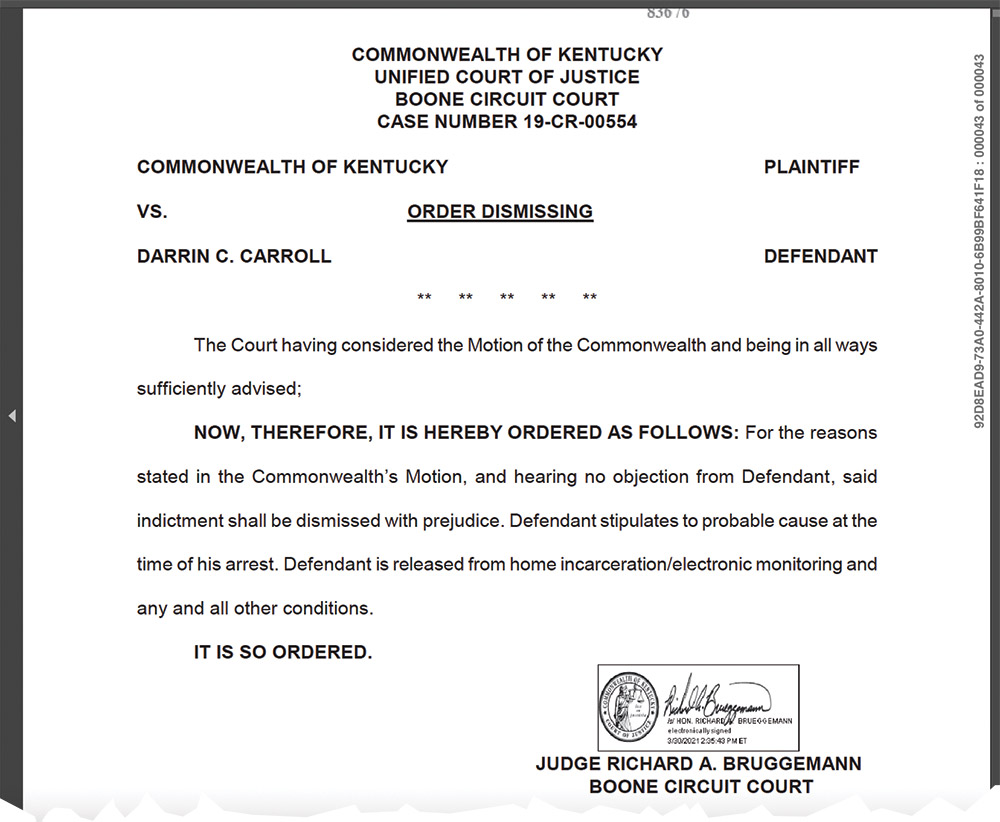

A police report placed most of the blame for the fatal crash on Darrin Carroll (bottom, at a Boone County, Ky., court appearance shown on the WKRC television news website), who was arrested, charged and jailed. But attorneys for Amy Skiba’s children helped convince prosecutors to drop the charges, even as Eaton Asphalt Paving continued to blame Carroll’s allegedly negligent driving for the tragedy.

Photo credit: Screenshot of WKRC Channel 12 website; Kentucky

*Click on the image for greater detail

In Kentucky and in the suit determining who was negligent in Amy Skiba’s death, the legal stars aligned against Eaton Asphalt Paving: Darrin Carroll’s truck was uninsured, the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet staff had immunity under state law and Kentucky, unlike other states, has no cap on punitive damages.

Eaton Asphalt Paving’s parent company, Jurgensen, had insurance policies provided by a group of major construction insurers, including Zurich, Chubb and Liberty Mutual. Eaton Asphalt’s excess insurance limit with Liberty Mutual was $25 million. Jurgensen’s commercial general liability and umbrella policy with Acuity, A Mutual Insurance Company, carried limits between $10 million and $50 million.

But some insurance policies don’t cover punitive damages, and in the case of smaller companies, big damage awards can go far over the policy limits. Eaton Asphalt Paving did not respond to requests for comment, and insurers never discuss payouts. Plaintiff cases “are driven by where’s the money and how do I get to it,” says Brian K. Stewart, a Pasadena, Calif., attorney who defends insurers and public agencies against claims. “They are very hard cases to defend because you have very sympathetic clients on the plaintiff’s side, and jurors are people. Making that connection is not hard to do, but to spin it into a nuclear verdict is a skillset not every lawyer has.”

Jay Vaughn and Ronald Johnson Jr., attorneys at Louisville-based law firm Hendy Johnson Vaughn Emery, represented the family. During a video and podcast geared toward personal injury attorneys, they explained in detail the skills they applied and the luck that helped them reach the huge damage award. The attorneys sought and received an early trial date, one year from the lawsuit, and promised the judge that five days was enough for the trial. According to Johnson and Vaughn, Eaton Asphalt Paving attorney Richard Rinear sought a longer trial. He did not reply to requests for comment.

Injury cases brought by victims “are very hard cases to defend because you have very sympathetic clients on the plaintiff’s side, and jurors are people.”

- Brian K . Stewart, California attorney

At one point Kentucky Transportation Cabinet employees were also named as defendants, but the charges against them would be dismissed on summary judgment. Vaughn and Johnson supported the employees’ motion to have charges dropped. “That was one of the best decisions we made,” said Johnson.

Diminishing another culpable party’s importance was the next successful order of business. Six months after the accident, a Boone County grand jury had charged Carroll with one count of second-degree manslaughter, three counts of first-degree wanton endangerment and one count of driving under the influence-third offense, plus speeding. A local television report and website showed photos of Carroll’s appearance in criminal court, dressed in prison stripes, as he stood before the judge requesting him to set a lower bail.

In an amended complaint, Vaughn and Johnson removed Darrin Carroll as a defendant, but he remained a key figure in the lawsuit against Eaton Asphalt. Vaughn and Johnson developed a strategy that turned Carroll into a victim, too. Although no longer a defendant, jurors would be asked in a formal document to apportion negligence with percentages to either Carroll or Eaton Asphalt Paving. Any contribution to a potential damage award would, if Carroll was found negligent in large part, come from a comparatively paltry uninsured motorist insurance claim payout.

Some tact was required to get the charges against Carroll dropped. In January 2021, Vaughn and Johnson discretely let the prosecutor read depositions with their questions and answers on the edge-drop hazard. “We didn’t want them to think we were bombing their case and didn’t put a spin on it,” said Vaughn. The prosecutors, with the support of the family, soon moved to have the charges dismissed, saying the evidence no longer supported the accusations. In the YouTube video reviewing the case, Johnson said “that was one more thing we got right.” How the case looked at that point to Eaton Asphalt Paving isn’t clear.

Kentucky is One of Many States That Has Studied and Promoted Safety Edges

For roughly a quarter century, both federal and state officials —including those in Kentucky—sought to replace dangerous drop-offs on asphalt-paved roads, reshaping the edges into 30° slopes to allow drivers who unexpectedly drift off to safely return to the road.

Slopes are created on new surfaces with a shoe or other attachment to the paver, or by using a wedge-shaped configuration at the shoulder.

Research on the issue can be found as far back as the late 1970s and 1980s. In 1994, the American Automobile Association’s Foundation for Traffic Safety issued a report highlighting the “hazards of pavement edge drop-offs.”

The Federal Highway Administration in 2006 teamed up with AAA on an even more comprehensive review of the issue. The resulting 124-page study included detailed explanations of the dynamics of often-deadly crashes triggered by pavement drop-offs, plus state efforts to curb the hazard with safety edges and other measures.

The report reviewed a variety of potential accident scenarios involving cars and other vehicles driving off the road edge. These include the “typical pavement edge drop-off-related crash,” which, the report notes, “entails running off the road to the right, over-correction, and then crossing the centerline.”

The report also attempted to quantify the magnitude of edge drop-off on rural two-lane paved roadways, looking closely at Iowa counties and two Missouri districts. The authors found a small but still significant number of all accidents along these roads, somewhat less than 3%, were either “probable” or “possible” in terms of being “edge drop-off-related.”

Edge drop-off related crashes in Iowa were much more likely to be fatal–four times the rate of all rural crashes.

—U.S. Federal Highway Administration

However, edge drop-off related crashes in Iowa were much more likely to be fatal–four times the rate of all rural crashes. They also were twice as likely, at 11.3% of all “probable” and “possible” edge drop-off-related crashes, to involve major injury, the FHWA report found. Similar results were found in other states, including North Carolina.

The 2006 report also had another finding highly relevant to the tragic 2019 Kentucky car crash that led to the court case Alton Godwin et al. v. Eaton Asphalt Paving et al.

One major type of liability lawsuit filed against state agencies involved accidents in which edge drop-off is cited as a major factor. In Iowa, “pavement/shoulder edge” or “shoulder conditions” accounted for 38% of claim amounts in lawsuits filed against the state transportation department in 2000 through 2003. However, in Iowa’s case, the state DOT argued that it had been successful in defending against claims due to a “strong maintenance policy.”

Iowa is not alone, with several other states having pushed to reduce the number of accidents and fatalities caused by pavement edge drop-offs. California, for example, in 2012 revised rules for hot-mix asphalt paving to require safety edges.

The Kentucky Transportation Center and the University of Kentucky College of Engineering co-authored a report on the issue, released in 2015. It tallies the myriad ways that Kentucky highway officials were attempting to cut down on the incidence of “roadway departures” that are “a leading cause of roadside fatalities.”

Kentucky officials said that their focus has been on “several low-cost, systemic roadway safety treatments,” including, but not limited to, safety edges, cable barriers, high friction surface treatments and rumble strips.

At the time of the report, the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet had installed 147 safety edge “treatments” along 580 miles of roadway. Other states have continued to experiment with different attachments. Washington state in 2013 studied four projects built using four different special devices attached to the paving machine.

The 2006 federal study did not include Kentucky, but it did look at 10 states plus British Columbia. All required contractors to bring roadway shoulders back up after repaving projects, although states had different interpretations as to the height at which an edge would be considered hazardous. The federal report urged state highway authorities to make eliminating dangerous drop-offs a top priority and to promptly remediate any edge drop-off that meets or exceeds a prescribed threshold. The report also called for highway departments to offer extensive training on the issue for their own staffs and those of road contractors.

By Scott Van Voorhis

Routine Paving Contract

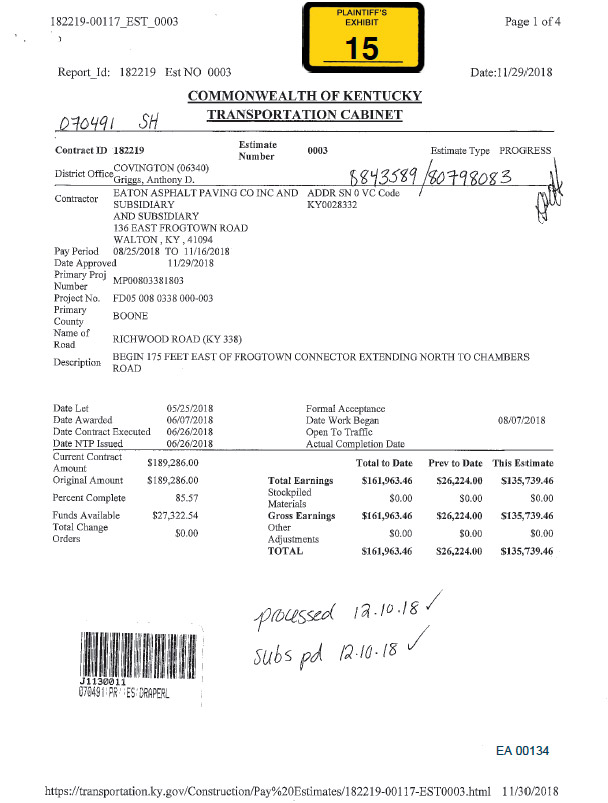

The company has been one of the mainstay contractors for the state transportation agency, especially in Kentucky’s District 6 that includes Boone County. The state awarded Eaton Asphalt Paving the 1.68-mile Richwood Road repaving contract after a bid competition, at the price of $189,206.

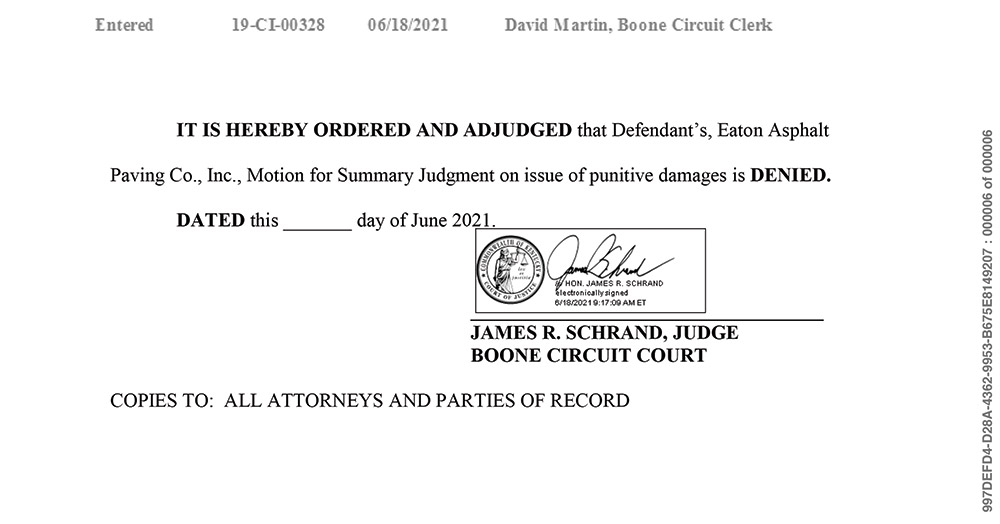

Little that is remarkable happened as crews performed the construction work from June to November 2018. During the project, Eaton Asphalt employees and supervisors were in regular communication with the Kentucky agency. At one point, the contractor’s crew asked cabinet staff if the firm could forego milling the existing surface of the Richwood Road stretch that was getting repaved. Exactly why and on what terms that permission was granted became a focus of both pre-trial depositions and the five-day trial that started on July 7, 2021 in the Justice Center in Burlington, the Boone County seat. Judge James R. Schrand presided.

Eaton Asphalt Paving’s failed attempt to stop the judge from allowing punitive damages was made partly by showing that safety edges would not have worked.

Image courtesy Commonwealth of Kentucky court records

The maneuvering began even before a jury was seated, with both sides agreeing not to bring up to the jury Carroll’s prior two misdemeanor DUI arrests, but company attorney Rinear reserved the right to include toxicology reports taken after the crash. After settling that and seating jurors, he told them in his opening statement: “We’re never going to get the truth out of Darrin Carroll” and “it’s not our fault he drifted off the road.”

A parade of witnesses testified, including Carroll, who was treated gently by the plaintiff’s attorneys, police and expert witness crash investigators. Much discussion and testimony concerned how asphalt roads were built: a simple asphalt overlay, milling, safety edges made with a wedge configuration of the asphalt and differing conditions at the shoulder or edge.

Vaughn and Johnson did everything they could to convince the jury that Eaton Asphalt Paving had violated the terms of state specifications that bound the contractor to use a safety edge of some kind. Although the case was not about contract compliance, but rather about negligence causing or contributing to Skiba’s death, Eaton Asphalt’s alleged betrayal of its contract terms—and the apparently informal way the safety edge requirement was suspended—became a crucial element in the story that Vaughn and Johnson wanted the jury to embrace.

*Click on the image for greater detail

In a deposition before the trial, Kentucky Cabinet section engineer Anthony Griggs testified that in more rural areas, where there is no curb and gutter along the road shoulder, “we generally don’t always mill” as a way to avoid raising the road surface higher than the soil and grass alongside.

The plaintiffs’ attorney then asked why, if the re-surfaced road creates a surface that is higher than the grass and soil alongside, did Griggs allow Eaton Asphalt’s request not to mill some sections? He replied that it was because he expected the company to comply with the specification anyway by using a wedged configuration of the asphalt it planned to apply to produce a safety edge.

One of the plaintiffs’ attorneys asked during the depositions, “Did you ever tell Eaton that they had improperly constructed” part of the project?

“I had not,” answered Griggs.

The attorney then queried whether the fact that Eaton Asphalt overlaid this section of roadway and did not properly construct the safety wedge made the section more dangerous than it was before the project began.

At that point, Rinear objected, but before Griggs could be stopped, he answered: “Potentially, yes.”

During the trial, under questioning by Johnson, Griggs built upon his deposition statements. He testified that there are very few conditions on a two-lane road that would limit the use of a safety wedge; that if a contractor has issues with road conditions, or thinks they would prevent the use of the safety wedge, such issues must be brought to his attention.

Plaintiffs’ attorneys Vaughn and Johnson did everything they could to convince the jury that Eaton Asphalt violated the terms of state specifications that bound the firm to use a safety edge of some kind.

Griggs also said the safety edges can be installed not only on an “improved” shoulder but also on an existing shoulder. Johnson then asked him: “Can a paving wedge on a two-lane road even go down to where the edge is grass?” To which Griggs simply replied: “Yes.”

Under cross-examination, Griggs said that it was the contractor’s responsibility to get it right. “If during the work you’re unhappy with how the edges are being constructed, do you have the right to have the contractor redo them?” Rinear asked. Griggs agreed, but said that was not done on the Richwood Road section.

Late in the trial, on day four, Rinear brought to the witness stand Eaton Asphalt superintendent Delbert Endres, a 40-year employee who is in charge of paving and milling crews. His comments were consistent with statements by other Eaton Asphalt staff that they had been excused, informally, from building safety edges on about 100 prior projects. As for the attachment to the paving machine gate to create the safety edge, referred to as the shoe, Endres testified that Eaton Asphalt had not “used it in six years” because the design “was not working for the state.”

“If you’ve got a four-inch drop and you’ve got a wedge and it goes to a ditch, the asphalt just runs down into the ditch,” Endres said. “It doesn’t do any—it doesn’t give you a—you know, the 45 degree angle, what they’re looking for,” and the state “pushed it off.”

Rinear asked him, “Do you ever pour asphalt just onto grass or dirt or mud?,” to which Endres replied that it would be foolish because the asphalt can’t be well compacted. “You’re wasting material,” he said.

In cross-examination, Johnson showed to Endres photos of some edges on the Richwood Road segment with as much as a 6-in. drop. He cornered Endres into agreeing that such a drop would be hazardous and that the authority for not putting in a safety edge rested with Griggs and the Kentucky cabinet alone. Johnson also pressed Endres, asking him on which memo or with what phone call the cabinet had informed contractors that they no longer had to install safety edges as required in the specifications. “They just kind of phased it out,” was Endres’ best reply.

Summations followed, with Judge Schrand then giving instructions to the jury. After four hours of deliberation, jurors on July 12 returned a verdict—holding Carroll 0% responsible for the accident and ordering Eaton Asphalt to pay $74 million. At that point, the parties agreed to reach a settlement. The amount was not made public.

What about the future of safety edges on two-lane asphalt roads? A telling example is California, whose rules seem to speak to the limits as well as to the benefits of safety edges. In a memo to state transportation agency district directors in 2012 from its deputy director of operations and maintenance, the state revised hot-mix asphalt rules for safety edges.

The safety edge treatment is to be placed where there is a “solid base, free of debris such as loose material, grass, weeds or mud,” the rules say. California specifically excludes use of safety edges next to curbs, guardrails and walls, near driveways and where the overlay is just below 2 in. deep.

That’s deeper than the thin overlay put on the repaved section of Richwood Road where Darrin Carroll’s truck hit Amy Skiba’s Honda.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment