Bechtel Eyes Milestone in Epic $17B Megaproject

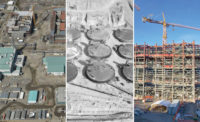

Hanford federal waste site workers soon are set to finish building the first plant (foreground) to treat long-stored nuclear material, part of a 16-year effort to construct the huge immobilization complex.

IMAGE COURTESY OF BECHTEL

As Bechtel National Inc. received 40 tons of steel earlier this month to build a 45-ft-tall evaporator tower on an effluent management plant at the U.S. Energy Dept.’s Hanford nuclear waste site in southeast Washington, project officials saw it as a hopeful sign they could finally soon begin making vitrified glass from 56 million gallons of chemical and radioactive waste—stored underground since World War II—at the huge former atomic weapons complex.

Work has continued since 2002 to build the technically complex and controversial Waste Treatment and Immobilization Plant or “vit plant.”

Under close federal and state scrutiny, its price tag has climbed to $16.8 billion. Officials of Bechtel, the project director, and DOE say they are on track to soon complete the first key plant in the complex that will treat “low-activity” radioactive waste—which contains small amounts of radionuclides—years ahead of more contaminated materials. Originally, both were to be treated simultaneously.

Sequenced Approach

In a sequenced approach, which officials say will expedite the project and provide operating experience, low-level waste will move directly from underground tanks to the designated plant for vitrification. The effluent management facility being built will evaporate secondary liquids generated from waste melting and from flushing of waste transfer pipes, and return remaining concentrate for added vitrification.

The low-activity waste plant, along with an analytical lab and 20 support structures, are set for startup this summer, says Bechtel project director Brian Reilly.

Work on a waste pretreatment facility and the high-level waste treatment plant remains on hold. In an April online company post, Reilly said Bechtel expects to “sufficiently resolve” by year-end the remaining pretreatment plant technical issues.

Bechtel and DOE staff last year completed testing of full-scale vessels “that indicate we can meet” DOE nuclear quality, safety and performance requirements, he said.

Quality-assurance issues on the project were targeted in an April review by the U.S. Government Accountability Office that recommended more QA independence.

Responding to the concerns, Ann White, DOE assistant secretary for environmental management, said the current approach was being reassessed to confirm independence from cost and schedule influences. A DOE review of how Bechtel is implementing a 2014 “management improvement plan” is set to finish by year-end, according to the Tri-Cities Herald, a Hanford-area newspaper that has closely followed the project.

Framework

Bechtel issued this spring a 7,000-page safety analysis—a three-year project—which sets the framework for start-up and “provides further confidence” that the facility can safely treat low-level waste, says a DOE site manager. Its completion could generate up to a $6.65-million bonus for the firm under the contract, says the newspaper.

Tom Carpenter, executive director of Hanford Challenge, a Seattle group that monitors site cleanup accountability, says he supports vitrifying Hanford tank waste but has concerns about possible vit-plant design flaws, QA/QC issues and a poor nuclear-safety culture across the complex.

DOE has a court deadline to treat low-level waste by 2023 but Bechtel is contractually obligated to start the process in early 2022.

Full vit-plant operation is mandated by 2036. Bechtel’s contract includes other incentives for early completion and penalties for unmet deadlines.