Hampton Roads in Virginia—seven communities and 11 federal facilities—is facing one of the worst combinations of erosion, subsidence and sea-level rise in the nation. The latest modeling suggests the area faces a sea-level rise of between 2.5 ft to almost 7 ft by 2100. Acknowledging that it is not practical or affordable to build a fortress around the entire region, the communities and agencies are working on plans that will allow them to live with the water.

Hampton Roads in Virginia—seven communities and 11 federal facilities—is facing one of the worst combinations of erosion, subsidence and sea-level rise in the nation. The latest modeling suggests the area faces a sea-level rise of between 2.5 ft to almost 7 ft by 2100. Acknowledging that it is not practical or affordable to build a fortress around the entire region, the communities and agencies are working on plans that will allow them to live with the water.

George Homewood, planning director for Norfolk, says the city explored the idea of building flood gates and floodwalls, but it learned that “the cost of doing so—in terms of the environment, in terms of our way of life, and in terms of the city, state and federal governments’ checkbooks—are way too high.”

Instead, the city is looking at ways to protect parts of the city while “living with water” in other parts of the city. Under its new “Vision 2100” plan, the city is conducting asset mapping to identify what needs to be protected, what doesn’t need to be protected and what can be relocated. In some cases, the city plans to reverse past efforts, such as daylighting creeks. “We thought we were smarter than Mother Nature, and we spent a lot of time filling in creeks,” Homewood says. “Turns out that draining the swamp is not always the right answer. We filled in creeks, and we put roads on many them—and that’s exactly where we’re getting floods today.”

Norfolk’s Chesterfield Heights neighborhood in 2014 got a financial boost from Virginia Sea Grant to develop a resiliency plan to address the neighborhood’s recurrent flooding issues. Students from Old Dominion University and Hampton University crafted a plan that includes a living shoreline, a series of cisterns, permeable pavement and bioretention gardens.

CHESAPEAKE BAY Relative sea level rose as much as 1 ft in places in the Chesapeake Bay in the 20th Century: 6 in. from subsidence and another 6 in. from warming and rising seas.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers currently is working on the Norfolk Coastal Storm Risk Management Study, which will suggest adaptation strategies for the region. Structural options under consideration include floodwalls, tidal gates or levees, flood-proofing structures, and either elevating structures or acquiring structures and removing them from the building stock, according the Corps. The final report is due in January 2019.

Naval Station Norfolk is less that 10 ft above sea level, and tidal flooding is already a common occurrence. According to a Union of Concerned Scientist report, under an intermediate scenario, low-lying locations in and around the base would experience about 280 tidal floods per year by 2050. In the worst-case scenario, the base would see 540 floods. The level of flooding may render some areas unusable within the next 35 years, the report forecasts.

Still, Ray Toll, director of coastal resilience at Old Dominion, says the Navy does not plan to build a fortress around the base against flooding because it would flood the surrounding area, where most of the personnel live. “We’re finding that routine thunderstorms are now flooding streets, which prohibits sailors from getting to and from the base,” he says. “That delays them or basically shuts them away from the base. They can’t even get to work.”

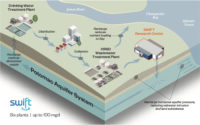

Subsidence projects are also underway in the region. The Hampton Roads Sanitation District is building a $25-million demonstration project in Suffolk, Va., that will treat water to the geochemistry of the area’s aquifer, then pump that water into a recharge well to permeate through the aquifer’s surrounding sand layers. If successful, the project could provide a way to refill the area’s shrinking aquifer and slow the associated land subsidence. Such results ultimately could lead to $1 billion in projects at seven of HRSD’s nine wastewater treatment plants. ♦ with Pam Hunter McFarland

How Engineers Are Preparing for Sea-Level Rise

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment