|

| IMAGING Scientists can "see" animal brain activity using noninvasive tools. (Photo courtesy of Salk Institute of Biological Studies) |

In an effort to prove beyond scientific doubt a relationship between design and human health, well-being and worker productivity, the American Institute of Architects is embarking on an historic path that may result in a new discipline of science. Sources call it "neuro-architecture."

AIA recently announced two unprecedented research initiatives, one with the Salk Institute and the other with the U.S. General Services Administration and the National Institutes of Health. They are intended to show empirically that different physical environments affect brain activity and even change brain structure. The projects, though in their infancy, could have a major impact on how the workplace, buildings and even towns and cities are planned, designed and retrofitted, say sources.

"I believe that good architecture can increase your productivity, elevate your sense of well-being and cause you to heal more quickly," said Norman L. Koonce, Washington, D.C.-based AIA's executive vice president and CEO. He spoke at the AIA 2003 National Convention and Expo in San Diego, May 8-10. "I believe we can prove that [good] architecture can [even] increase longevity," he said.

Koonce thinks the "biggest problem" will be getting interest in the research from architects, some of whom might feel their creativity would be stifled by the scientific method.

He doesn't have to convince the San Diego AIA chapter. The legacy project for this year's convention is the Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture. The academy touts itself as the first institution to explore how humans perceive the built environment and how they respond to it.

The fledgling nonprofit, which has an advisory board of architects and scientists that reads like a Who's Who in neuroscience, initially intends to study office worker productivity, primary school learning and "healing by design" for Alzheimer's patients. Experiments will track human brain neuron firings in a noninvasive way.

Supporters want to prove the hypothesis that "the environment, the structure we live in, affects our brain and our brain affects our behavior," said Fred H. Gage, professor at Laboratory of Genetics, Salk Institute for Biological Studies, La Jolla, Calif. "It's time we work together to collect the beginnings of the information," he said during a keynote speech at the convention, which drew a record 20,000 attendees.

Gage and others are proposing a merger of the disciplines of neuroscience and architecture. "We need to impose empiricism on architecture," said Gage. That may be a challenge to the sensitivities of the architect, he admitted.

|

Tests will involve stimulating brain activity. Subjects can be humans, rather than mice or rats, thanks to noninvasive tools such as magnetic resonance imaging and other brain scanners.

Many see a day when architecture as a clinical science is used to promote health and eliminate disease. "This could be a whole new field of science," said John Eberhard, AIA's director of research planning and the 2003 recipient of the AIA College of Fellows $100,000 Latrobe Fellowship, which he will use to gear up the academy.

The academy is in a fund-raising mode and is laying groundwork for how information can be disseminated and how neuro-architecture can be incorporated into architecture school curriculums, said Alison Whitelaw, president of the San Diego Architectural Foundation, a member of the academy's board and a principal of Platt/Whitelaw Architects Inc., San Diego.

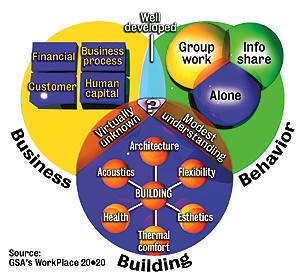

AIA also is under a roughly $500,000 contract with GSA's Public Buildings Service to explore stress and the workplace. "We're trying to quantify the relationship between behavior, the built environment and organizational performance...," said Kevin Kampschroer, research director for PBS's WorkPlace 2020 program, which has a total of 22 projects planned, and seven, including the AIA's, under way. PBS is responsible for 340 million sq ft of office space, of which half is leased, and a $2-billion-per-year capital program for renovation, repair and new construction of government buildings.

The GSA-AIA-NIH research will use 70 PBS employees, gathering data from each through 24-hour periods. After baseline data is collected, researchers will change workplace variables, such as lighting, heating, air conditioning, color, noise, privacy levels, window proximity, even walls, and give the subjects cognitive tasks to perform under the different variables.

PBS will use two techniques to measure stress. One is a small monitor, attached to a belt, to measure variables in heart rate, which gives indication of brain activity. The other is an arm patch that collects drops of sweat that can be broken into 50 hormones, which determine biological balance. In conjunction, subjects will be given a personal digital assistant to input activities.

|

Measuring people's stress response is "feasible and available this minute and has been applied in other settings," says Esther Sternberg, a medical doctor involved in the GSA-AIA research and director of the Integrative Neural Immune Program at NIH, Bethesda, Md. "This is not pie in the sky."

The study will not be done until NIH gives the green light, hopefully in the next week, says Eberhard. Results could come by year-end.

Sources say it will be at least 10 years before there is an understanding of the neurological underpinnings of design. GSA's WorkPlace 2020 program should be done in two to three years.

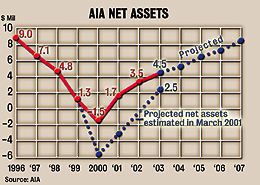

AIA reports it is getting its own house back in order after a decline in financial health. First quarter net income is $12.9 million, which is 2.6% ahead of the budgeted goal, said Koonce. Total net assets hit $3.5 million in 2002, as projected (ENR 5/20/02 p. 12). By 2007, AIA projects it will have almost $9 million in total net assets, which is about what it had in 1997 when the decline began.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment