|

The Los Angeles Unified School District, the second largest in the U.S. with 750,000 students, had literally run out of space and couldn't figure out how to accommodate its exploding school-age population. The symbol of the district's failure was backpack-laden kindergartners boarding banana-colored buses shortly after dawn for the long ride to schools far from home.

When LAUSD did try to catch up, much went wrong. Perhaps most infamous is its Belmont Learning Complex, an $87-million high school facility partially built on a site later found to be fouled with methane and chemicals. The incomplete structure was abandoned in January 2000. Neither the public nor the press believed the district could be an effective builder. The same problems that plagued LAUSD operationsa large, unresponsive bureaucracy and a highly politicized school boardseemed likely to doom its major construction program as well.

Los Angeles' former Mayor Richard Riordan had no formal authority over the elected board, but backed a political action committee that supported new school board candidates who ran and won. The new board majority moved quickly to suspend district employees who they considered culpable for the Belmont fiasco, hire a new schools superintendent and, most importantly, adopt a master plan for construction. The board also established new jobs for seasoned construction pros, including someone to jump-start its stalled and troubled school projects.

Littmann previously had studied LAUSD's problems as a task force volunteer. So when the idea of working for the district came up, Daniel A. Rosenfeld, Littmann's boss at Los Angeles-based developer Jones Lang LaSalle, urged officials to consider her.

LAUSD had only opened 24 new schools in the past 20 years, and not a single high school during that time. Its small real estate department was a mess. Littmann told herself she had to be crazy to take the job. She took it. For just six months, she told herself.

Littmann eventually stayed for three years, only recently leaving the district to launch a new school facilities consulting firm. "I just got hooked," she says. "I could have had other jobs with a lot more time for myself and a lot more money, but I couldn't walk away from it."

Once hooked, "citizen Littmann" didn't disappoint as school construction chief even though she faced monumental obstacles. Looking ahead to a June 2002 deadline for applying for state construction funds, Littmann built a staff of district employees and consultants, wrote new standards and procedures, bought hundreds of acres of hard-to-find, hard-to-secure real estate and completed stamped architectural plans for 160 new projects. With titles and plans in hand, LAUSD rushed its material up to skeptical state officials in Sacramento and won another $916 million in available funding. District officials then convinced voters last November to approve another $3.35 billion for new work.

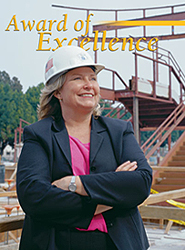

For her exceptional public service in re-invigorating the Los Angeles Unified School District's critically needed construction program, the editors of Engineering News-Record name Kathi Littmann the winner of its Award of Excellence for 2003.

|

| JUMPIN' Littmann focused on kids, like these primary schoolers. (Photo above and top by Michael Goodman for ENR |

Littmann's modus operandi included rising above the political fray and turning her work into a noble civic cause. "Her most compelling feature is her desire to do something profound for the kids," says James A. McConnell Jr., the district's chief facilities executive and Littmann's former boss.

"I didn't hire anybody who didn't share that passion," Littmann says. The worst overcrowding, in the poorer, immigrant-filled neighborhoods, is an inequity that needs to be corrected, she says. For guidance on how to build with the least disruption to affected communities, Littmann reached out to parents and to community groups, both of whom had learned long ago to expect little but heartache from LAUSD. And she went out of her way to hire good architects and stimulate them to produce quality designs, and even inspiring ones, that could become new centerpieces of community life.

By sowing good will and pursuing her task with fanatical devotion, Littmann made herself the indispensable woman in an urgent urban task. "She was everywhere, working with everyone, to get the job done, a job that very few people thought had the slightest chance of success," says Thomas A. Rubin, consultant to the School Construction Bond Citizens Oversight committee. "I won't say that it could not have been done without her, perhaps it could have been, but I can't think of anyone who would have liked to try."

Littmann imparted a sense of possibility and mission, says Glenn Gritzner, special assistant to school superintendent Roy Romer, the former Colorado governor recruited into the district in 2000. Romer himself credits Littmann's straight-arrow midwestern ethics for her ability to "always cut it straight" in making tough, ethical choices. Some admirers believe Littmann's service will be remembered for having changed the face of Los Angeles.

|

| ALL ABOARD Students must commute to schools outside their district to find a seat. (Photo by Michael Goodman for ENR |

FALLING BEHIND

With immigrants pouring in and population surging by tens of thousands each year, California's schools are among the most crowded in the nation. The state's School Facilities Planning Division estimates it will take $7.27 billion to build all the new schools needed in the next few years. The state predicts that, by 2010, it will have 1 million more students than it had at the beginning of the 21st century.

California's inability to keep up also stems from Proposition 13, the 1978 culmination of voters' anti-tax sentiment. That measure, and its offspring, have limited local government's right to raise taxes and made local school districts more heavily dependent on the state for construction funding.

|

Los Angeles frequently lost out when it came time to claim its share of state funds. Partly out of its own ineptness and partly due to the challenges of finding new school sites without environmental problems, LAUSD struggled to document its needs and claim state money. Some Angelenos feel Sacramento deliberately did all it could to keep their city down, but state officials dispute that. "It was first-come, first-serve, and they could not compete," says David Zian, manager of fiscal services for the State Allocation Board. "They were good people in a tough situation."

DAWN RITUAL

A familiar ritual unfolds every weekday morning on the sidewalks outside Cahuenga Elementary School in central Los Angeles. About 1,400 children blithely line up and board 40 buses that carry them to schools around the metropolitan area, some a full hour away. On a recent February morning, some parents lingered protectively near the queuing children until the buses pulled away.

No other city in America requires as many children, close to 16,000, to ride buses every day because of overcrowding. And few use as many bungalow-type temporary classroom structures on a permanent basis. Regular school buildings are better maintained now, says Genethia Hudley Hayes, a board member whose area includes South Central Los Angeles. A few years ago, some were so bad "I wouldn't have left my German shepherd there for the day," she says.

Another method used to cope with overcrowding is LAUSD's system of year-round, multi-track scheduling, mysteriously termed "Concept 6." The approach lengthens the school day but shortens class time and requires students and teachers to rotate over the year, forcing some to be in classes in summer months. Some estimate that, under Concept 6, a student will have spent one entire school year less in class by the time he or she has completed high school.

Jeannie Oakes, a University of California-Los Angeles professor who specializes in educational inequity, says that Los Angeles now operates more multi-track schools than any other large city in the U.S. Students on such schedules as well as those who take buses score lower on standardized tests, she contends. "The main goal of LAUSD's construction program is, and has been for some time, to build enough schools to return all its students to neighborhood schools operating on traditional calendars," Oakes wrote in expert testimony submitted in one lawsuit.

ROCKY START

Some Los Angeles residents responded to school overcrowding by suing for improvements in 1992. The state settled one lawsuit by agreeing to thin out densely occupied classrooms. In 1997, school district voters passed Proposition BB, which provided $2.4 billion mostly for repairs and modernization.

But not surprisingly, things got off to a rocky start. Many administrative jobs at LAUSD were performed by former teachers and educators, including staff involved in facilities management and real estate. When employees failed to perform, LAUSD simply shifted them to other jobs in the district. Senior staff considered responsible for the Belmont fiasco were suspended, shifted to other departments or agreed to retire.

|

| (Photo by Michael Goodman for ENR) |

As the Proposition BB work got under way, district staff seemed unwilling and unable in the highly political atmosphere to make key decisions on construction projects. LAUSD spent millions of dollars on program management and project management fees, but progress on repairs and modernization came slowly. The work required environmental approvals and often had to be done a class at a time in occupied buildings. Lines of authority often were confused. The program manager, a joint venture of 3D/International, Houston, and O'Brien-Kreitzberg, San Francisco, as well as numerous project managers, reported to LAUSD's chief administrative officer rather than its facilities services department. A school district Inspector General's report found chaos in the handling of projects and said that consultants' fees were above national averages. 3D/I officials claim the report made incorrect assumptions related to calculating fees based only on design management and land acquisition. The firm is still employed by the district.

In the 1990s the district had been overly eager to acquire property and had purchased about a half dozen sites easily "because they were polluted," says Angelo Bellomo, who currently is in charge of environmental due diligence.

The new construction program was moving at a glacial pace as LAUSD confronted what other districts in land-starved areas around the country facedfew affordable sites free of environmental problems. To find potential sites, the district's tiny real estate staff hired a single consultant who drove around the city looking for promising property. Site acquisition then languished through a lengthy, out-of-date approval process that LAUSD staffers still scrupulously observed.

Littmann's crusade to untangle the convoluted mess she inherited at LAUSD has roots in her no-nonsense Middle- America upbringing in Bartlesville, north of Tulsa. Her mother, now retired, was a homemaker who later built a career helping technical and vocational schools develop computer networks. Littmann's late father was a newspaper pressman who later became a mason and contractor. Littmann began working as a teacher as she studied for her main career interest, architecture. Those studies moved around the U.S. as she and her husband, from whom she is now divorced, needed to move to accommodate his sales and marketing career. By the time Littmann arrived in Boston, she had two small children. So she took a part-time construction administration job for an architectural practice but then had a career epiphany: "I was sitting next to an architect with master's degree, and he's 70 grand in debt and making $25,000 a year, and he's drawing and has no authority," Littmann recalls. " I didn't want to do that, so I took a job with a small development company redoing one of the piers on the waterfront." Her Boston resume later included a stint at contractor Morse Diesel, now part of AMEC.

In the late 1980s, Littmann heard that Lehrer McGovern Bovis, the New York City construction manager, had won the job of building a new Disney theme park in Paris. She sent off a resume hoping to win a job in France. Former LMB Executive Vice President R. Sail Van Nostrand invited her to New York City to talk about a job, but it was to build the interior of a new office complex in Brooklyn. Although disappointed not to be going to Paris, Littmann learned much from her New York mentors, who included Van Nostrand and LMB's former CEO, Peter Lehrer.

Littmann says she enjoyed interiors work because it involved more direct client contact and progressed faster. "I have too short an attention span," she jokes. Lehrer remembers Littmann's tenacity. "With Kathi, it's always more than just doing a job," he says. Van Nostrand remembers her as "fearless and confident."

Eventually, Littmann moved to Los Angeles in 1994 to help develop a new LMB construction management office. She left two years later to join architect Gensler, which at that time sought to do project and program management for some clients. Littmann then got a call from Jones Lang LaSalle and the chance to work on, in her words, "the big, sexy" Dreamworks studio project.

|

| (Photo by Michael Goodman for ENR) |

With support from her public service-oriented new boss, Littmann also began meeting with local civic leaders and volunteers to ponder the schools mess. Their new group, called New Schools/

Better Neighborhoods, favored small schools planned with extensive community input and designed to be centers of community life, not just places for teaching kids. Littmann soaked up the ideas while investigating problems at LAUSD.

Click here to view LAUSD map and details>>

Click here to view LAUSD map and details>>

First hired as a district consultant and then as a $120,000-a-year employee, Littmann tried to enact those principles, says David Abel, a school reform advocate. But with no organizational chart, professional depth or time to experiment, she was forced into "triage-mode," he notes. Littmann had to "find sites, simultaneously start design and environmental review and hope for some miracles."

Some have described LAUSD's recent accomplishments as miracles, but others say they are the result of critical decisionmaking that might have paralyzed district managers in the past. Littmann was strongly supported first by LAUSD's temporary school superintendent, Ramon Cortines, and then by his successor, Romer, as well as by new board members.

But change didn't come without a price, and Littmann irritated some longtime employees. "Kathi Littmann? I hate her," says one current facilities services employee who declines to be identified. "She said we never built anything, and it isn't true, and she forced out some of my friends who worked at LAUSD for years." Littmann emphasizes that the district wasn't building fast enough, that some longtime staff moved to other district positions and that others became valuable members of the new team.

But Littmann's first management move was to bring in experts from private-sector construction and real estate firms, including Charlie Anderson, a former Lehrer McGovern Bovis project executive who had moved to California and was working as a consultant. He became the district's director of project management. "I wanted to do something that mattered," he says. Another was Edwin Van Ginkel, an Arthur Anderson real estate consultant. Dozens of other new hires followed, with the facilities services staff now numbering about 160.

Another important task was to evaluate LAUSD's consultants. Littmann and Anderson say they were surprised at the lack of real progress. Project managers were assigned to regions using traditional narrow work scopes but the various local school districts were not up to the task of directing them, says Littmann.

| VIDEO |

| Award of Excellence Winner, Kathi Littmann speaks about her tenure at |

| 1. Quick Time Player | Windows Media Player |

| 2. Quick Time Player | Windows Media Player |

| 3. Quick Time Player | Windows Media Player |

| 4. Quick Time Player | Windows Media Player |

| 5. Quick Time Player | Windows Media Player |

Pinning down the scope of work for safety and classroom technology was elusive. "The contract didn't call for it and the project manager couldn't organize the client," says Littmann. Similarly, program manager 3DI-O'Brien Kreitzberg did not have responsibility for obtaining environmental reviews. Frustrated consultants kept turning in invoices, however. "I had a $50,000 bill on my first day on the job for a project where no site had been selected yet," says Littmann. "When I asked what [the consultant] had done, I got a file box with a dozen empty files in it." Adds Anderson: "The attitude wasn't let's build it.' It was let's report it and bill it."

Littmann and Anderson began using new people from many of the same consultants for the new construction program, but there was a new understanding that they now would be accountable for acquiring sites and completing design. If the prospective consultant staff showed any hesitation in being able to get the job done, Littmann declined their services.

Acquiring the sites quickly became the next priority and more consultants had to be hired to investigate properties. The infamous long chart of procedures turned out to contain many "myths and legends, with no legal or regulatory or practical use," says Littmann. In June 2000, Littmann, the district and the school board decided to fast-track property acquisition and design for as many schools as possible. But that also meant that if voters did not approve more debt, LAUSD would be paying for work that was not actually funded. "The board at the time voted to [go forward], with the expectation that it would use bridge financing until the next bond was passed," says Littmann.

To win state money to help fund the projects, Littmann and LAUSD had to complete state environmental reviews of properties, obtain ownership or an order of possession and complete enough design for stamped and permitted drawings. These had to be submitted to the state architect for review prior to final approval by the State Board of Allocation.

Littmann focused her efforts on meeting the June 2002 state deadline, gearing all acquisition and design milestones to that. To ensure that enough projects would be ready, design had to begin before a property was acquired, even if it meant wasting some money if the land deal fell through, says Anderson.

With the Belmont fiasco still fresh in everyone's mind, state lawmakers in January 2000 adopted a law amending the state education code to require review of new potential properties by the state Dept. of Toxic Substances, to see if soil and groundwater would affect staff and students.

Completing the environmental due diligence could have been seen as an obstacle to the big goal of getting schools started, says Angelo Bellomo, LAUSD's director of environmental safety and health, whom Littmann credits for quick, thorough reviews. "There are a lot of people who are just plain anti-environment and a lot of people will use these reforms as another example of state agencies coming in with requirements that are overkill," says Bellomo. "I don't agree with that. I believe they are necessary and we've been able to work with these statutes and conduct the reviews" and still meet the funding deadlines.

|

| COMMUNITY MINDED Littmann loves to listen and started an extensive outreach program that sought out parents and put organizer Tony Arias to work. (Photo top by Janice L. Tuchman, bottom by Michael Goodman for ENR) |

On another front, Littmann established an extensive community outreach program to engage parents and neighborhood residents. She experimented unsuccessfully with an outside consultant in charge, but later developed internal expertise at LAUSD. "Kathi Littmann, from the very beginning, she was the person who brought community outreach to the district," says Tony Arias, one of about 11 "organizers" who work with families in every school district.

One difficult task was property condemnation, forcing families and businesses to move to make way for new schools. Reluctance to tackle this often politically sensitive mission was one shortcoming of the old LAUSD.

Selecting school sites and relocating owners and tenants embroiled Littmann in the ethnic resentment simmering in Los Angeles, where the rising number of Latino residents has been a major demographic shift. On her first day as a district consultant, she "realized how difficult it was," Littmann says.

At one controversial meeting in North Hollywood, focused on developable commercial property, attendees erupted when LAUSD board member Caprice Young discussed the need for a new school. "The back half of the auditorium was shouting racial slurs, some of the ugliest, basest expressions of human anger I had ever seen," says Littmann. "There was total rawness in the racism and anger."

Littmann also made her mark on design. Rather than ram through buildings with only cursory attention to design, Littmann made design quality a goal. She and her staff paid attention to big issues, such as sustainability, and smaller ones, such as making sure that local residents had access to restrooms when using a new school's community room after regular school hours. Still, the budget was tight and high schools needed to be built for $190 to $220 per sq ft.

There were other ways Littmann emphasized design. She hired former Gensler Principal Marv Taff, who put together a group of leading architects to serve on a design review committee. LAUSD prequalified 190 architects and allowed designers to compete for school jobs, even if they had never designed an educational facility. It was extra work for project managers but introduced new thinking, observers say.

|

| PLAYGROUND SPIRIT Littmann made siting and design of new schools into a civic cause. (Photo by Michael Goodman for ENR) |

For many designers, "it was the first time a client representative really challenged them in terms of design," says Robert Timme, committee head and dean of the School of Architecture at the University of Southern California. "In the end, architects started asking for another design review, and the committee went from being a gatekeeper to a true advisory group."

While many of the new schools will create practical and aesthetically pleasing public spaces for children and faculty, city agencies are also now talking about joint planning processes and a broader view of the future of the city, says Timme.

Of course, not everything went smoothly for Littmann. At a planned site of a high school in the South Central ward, residents protested against the location because it would require demolition of several old houses and relocation of longtime neighborhood residents. That decision is now on hold. In at least one other instance, Littmann and her staff failed to convince community members that their opinions were sought and respected, not just as LAUSD propaganda.

How long the school board's political consensus will last is up in the air, too. Construction supporters Hayes and Caprice Young lost re-election campaigns in March to candidates closely allied with the teachers' union. Young's opponent specifically called for an inventory of the district's available space and complained about the use of so many consultants. Young says she is worried that the new board "will decimate" the program and all that's been accomplished.

Littmann resigned from the LAUSD position last December to form a new consulting firm, Two Roads Consulting, that will advise school districts on construction methods, design-build and public policy initiatives.

Littmann eventually burned out from pushing herself so hard and not realizing that "after working for nine days straight, you have to take a day off," says former superintendent Cortines. She compares working at the district to "running a marathon in mud up to your neck."

Yet Littmann admits that there is much work to be done. The 17 current construction projects must be finished and another 134 must be bid this year. Siting and design for another 40 facilities must be carried out under the construction program's second phase. Land will be even harder to find.

Click here |

Littmann's successor, Guy Mehula, a former U.S. Navy construction commander hired last year by LAUSD, faces considerable challenges. About six projects are currently being bid and Mehula says he is trying to convince prospective bidders that LAUSD is now a professional and reliable client that will pay on time and respond quickly to questions regarding changes. The district has made great progress improving its reputation, but "you have to keep in mind that it is in the early stages of making changes" after years of distrust, says one school contractor.

Another potential problem are the expansion projects being bid in Phase I that are coming in far over engineers' estimates. Possible causes include stringent safety requirements and difficult urban sites that make it hard for contractors to work quickly.

As Littmann rushes from one meeting to the next, driving a car whose trunk rattles with a half dozen empty cans of Diet Coke, she often goes out of her way to credit others involved in the Los Angeles school program. Her intense three years at the school district turned out to be far more important than Spielberg's new movie studio or an office and retail development. Says Littmann: "I felt this was the most important job I could take on."

athi Littmann looked in her appointment book in July, 1999, and saw an unusual sightempty space. Just two years earlier, she had maneuvered herself into an enviable position as real estate consultant for a new movie production studio for director Steven Spielberg. The $200-million project would be the first production backlot built in Los Angeles in a quarter century. It was the type of exalted assignment that culminated a long journey, both in time and miles, for the Oklahoma-raised former schoolteacher, architecture student and contracting project manager. So when Spielberg's company, Dreamworks, pulled the plug on its studio plan, Littmann lacked one big project into which to pour her considerable energy. What happened next belongs to the fortunate history of Los Angeles civic life.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment