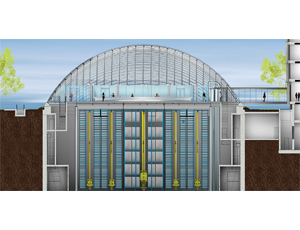

When the University of Chicago’s Joe and Rika Mansueto Library opens its doors in spring 2011 as planned, it will combine distinctive above-ground architecture with sophisticated underground support. Designed by Chicago architect Helmut Jahn of Murphy/Jahn Inc. and built by Barton Malow Co., the one-of-a-kind library will feature reading areas enclosed by a four-story glass-and-steel dome above a five-story-deep, climate-controlled underground storage vault that will protect and automatically deliver up to 3.5 million periodicals, books and rare research materials.

The Mansueto Library is being built at the heart of the University of Chicago campus, next to the Joseph Regenstein Library. To help keep irreplaceable research materials secure, the Mansueto Library’s only public entrance will be a 65-ft-long, glassed-in walkway connecting from the adjacent library.

Named after University of Chicago alumni Joe and Rika Mansueto, who donated $25 million for the $81-million project, the library design will add curb appeal but also save on operating costs.

The lot is only 163 ft by 360 ft, so the 120-ft by 240-ft oval glass dome “gives the site an open, airy feeling,” says Mike Natarus, senior project manager at the school. Storing books underground also uses less energy because the ground stays about 55° all year long, “so you need to heat only from 55° to the 74° temperature ideal for book preservation,” he says.

It will be the first building in North America to combine a slurry-wall foundation, an automated storage-and-retrieval system (ASRS) for books and a glass dome, sources say. The 38-ft-high dome will cover the 22,000-sq-ft ground-level floor, which includes a 150-seat reading room and circulation center, as well as preservation work areas.

A 50-ft-deep climate-controlled concrete vault will support the dome and ground floor, and house a 3,000-bin system that stores, delivers and retrieves books and research materials. “You can think of the entire building as a humidor for books,” says Natarus. Barton Malow broke ground in September 2008.

Test Preparation

The original plans called for a smooth-oval foundation. But when local subcontractor Case Foundation Co. analyzed the job, it found digging a smooth oval with a flat, 10.5-ft-wide trenching clamshell would be nearly impossible. “In 21 years in the foundation business, I’ve never seen an oval foundation before,” says Nicolas Willig-Friedrich, Case vice president.

Case proposed a modified design of 26 “facet” panels, each about 23.5 ft wide and touching at a slight angle. Local foundation designer Halvorson & Partners approved the change and handled permitting. Case excavated each panel in three sections: It first dug the left side, then the right side and finally the connecting section. Working 10 hours a day, it completed about 3.5 panels per week to finish the slurry wall in about 2.5 months.

The tops of the panels are locked together by a cast-in-place concrete ring beam that measures 5 ft high and 5.5 ft wide and covers the entire circumference of the oval. Containing about 500 cu yd of concrete, it will join the dome, the first-floor slab and the foundation below. It also will transfer all loads from the dome to the foundation. To help the beam retain its shape, the first-floor slab acts as a diaphragm. “Designing the ring beam was the most intensive part of the project,” says Jonathan Sladek, Halvorson senior project engineer.

After the slurry wall was completed in July, Chicago-based subcontractor John Keno and Co. Inc. excavated 53,000 cu yd of earth to dig the basement. As the hole reached specified depths, the concrete perimeter wall was tied into the surrounding earth with cable tiebacks, tensioned and pressure-grouted. “Because the library’s automated underground storage system requires 50 ft of clear height, the slurry wall acts both as a permanent earth-retention system and as the foundation that supports the main floor and dome above,” says Case’s Willig-Friedrich. In a normal underground structure, such as a parking garage, each floor slab helps brace the outer wall. But since there will be no slabs, the slurry wall is anchored permanently into the surrounding soil by 334 tensioned cables that reach out as much as 100 ft into the surrounding earth.

The area under the mechanical equipment room is the only part of the building that need caissons. Fifteen 2.5-ft to 3.5-ft- dia caissons were drilled to bedrock at depths ranging from about 31 ft to 48 ft.

It will take about six months to complete excavation and pour the 2-ft-thick reinforced concrete slab for the basement floor. When the slab is complete, structural steel will go in and the ground-floor deck poured. After that, the basement’s inner masonry and shaft walls will be installed 5 ft inside the perimeter foundation wall, followed by mechanicals. Starting this winter and continuing into summer 2010, crews will install mechanical, fire-suppression, plumbing and electrical systems. That stretch of the construction schedule will also see installation of the 50-ft-tall, 3,000-bin ASRS.

Once the ground-level floor is completed, crews will cap it off with the engineered dome, made of 160 tons of steel and 694 window panels, each 2 m by 2 m. Manufactured in Europe by German firm Seele Inc., it will take about almost two years to build and install.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment