TDR |

TDR |

For counterculture architect Eugene Tsui, biomimicry in design, considered the vanguard by some and still unknown to many, is old hat. Tsui has been living, eating, wearing and pushing biomimicry, where human creations copy nature’s systems, for 30 years—long before the movement had a name. And he has been practicing what he preaches, with 20 projects built, for over 15 years.

Biomimicry is “the only ultimate solution to many of the problems that have plagued humanity” since the beginning of civilization, says Tsui, who founded TDR Inc., Emeryville, Calif.

“The implication—and this is the most radical aspect of biomimicry—is that [the approach] destroys the image of the box, the gabled-roof home, the glass-and-steel skyscraper, the gridded, Cartesian plane of the city,” he says.

TDR |

TDR Tsui (top) built a house of the future prototype. Chinese tower (above) is coming in 2011. |

Tsui’s extreme positions have long ruffled the feathers of the architectural establishment. “The architecture world, as a whole, is reticent to take this on and is not supportive,” says Tsui. “They see me trying to imitate nature for the effect, but not for the understanding of how and why.”

Misunderstood or not, Tsui is no longer alone in his quest. Others agree that biomimicry has enormous potential for reducing human abuse of the planet.

“Life uses free energy, abundant materials and benign manufacturing, and life fits form to function,” says Dayna Baumeister, biologist and booster of biomimicry since 1999, when she cofounded Helena, Mont.-based Biomimicry Guild, with biologist Janine Benyus. Last year, the biomimicry duo celebrated the birth of the nonprofit Biomimicry Institute, based in Missoula, Mont.

|

Baumeister, who describes Tsui’s designs as more biomorphic than biomimetic, nevertheless agrees with his assessment of the design community’s historic resistance to biomimicry. “Most architects and engineers have a real disconnect with the natural world,” she says.

She plans to change that. “We have to teach biologists to talk to designers and the other way around.”

Toward this end, even the venerable Washington, D.C.-based American Institute of Architects, through its Committee on the Environment, is taking up the cause. On Jan. 31, in San Francisco, COTE and the Biomimicry Guild presented the first of five traveling workshops scheduled for this year on biomimicry in architecture. Another dozen are planned for next year.

Bnim Architects |

Bnim Architects Cambrian school would be ecologically friendly. |

Mimicking Life

Biomimicry means “to mimic life.” COTE and the guild advertise it as “a new discipline that studies nature’s best ideas and then imitates these designs and processes to solve human problems.” Biomimetic applications range widely from product design, engineering and architecture to software development, communication systems and organizational evolution. “Following 3.8 billion years of research and development, nature can suggest what works, what is appropriate, what lasts,” says the guild.

The Biomimicry Institute has several new projects to facilitate the practice of biomimicry in all walks of life. One is an Internet-based building portal for biomimetic architecture. A bigger effort is to use a Wiki-type model to build an encyclopedia of biomimicry that contains different systems in nature that might be applicable to design, from structures to products to medicine. “We’re talking about recreating the human genome project,” says Baumeister.

Having failed, to date, to get a government grant, the institute is seeking support from private industry and trying to penetrate the halls of education. Several schools have shown interest, including Georgia Tech, the University of Maryland and the University of Minnesota.

Pearse Partnership-Arup; |

Tsui’s first biomimetic project, a house addition in Eugene, Ore., was finished in 1981. It featured a wind-catching system, a rainwater catchment roof design, recycled wood beams, regional stone and more. It had a bright-orange roof made of recycled outdoor carpet permeated with oil-based reused industrial paint.

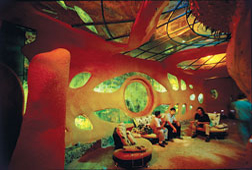

One Tsui-built project is a showcase for future living called the Ecological House of the Future. He has 120 projects designed, but not built, including nine that are active. One is a 600-meter-tall observation tower with 92 windmills, 700,000 sq ft of photovoltaic panels and a rain-catch device to be sited in the bay between Shenzhen, China, and Hong Kong. It is set for 2011 completion. Tsui also designed a biomimetic pedestrian bridge in Emeryville, Calif., that will span more than 200 ft over eight railroad tracks. It is set for completion next year. The first building in Tsui’s own Telos School and Design Laboratory in Mount Shasta, Calif., is set for 2008 completion and the final one in 2012.

Pearse Partnership-Arup |

Tsui has not used a mechanical engineer because most of his projects do not rely on conventional infrastructure. For structures, he works mostly with Clausen Engineers, an Emeryville firm.

Tsui may feel as if he is the lone architect on a quest for sustainable shelter. He isn’t. There are others, including Mick Pearce, currently of Melbourne, Australia, with the Pearce Partnership, in Harare, Zimbabwe. Pearce has worked with Arup engineers on two projects in Zimbabwe that have natural ventilation systems inspired by termite mounds: the Eastgate office and shopping complex, finished in 1996, and the Harare International School. Eastgate uses 10% of the energy of a conventional building.

Matthew Parkes |

Matthew Parkes Concept would provide water for a hydrological center using a beetle’s fog-catching ways.” |

When a student at Oxford Brookes University in the U.K., Matthew Parkes was inspired by the ability of the Namibian beetle to capture fog to quench its thirst. He developed a concept for a hydrological center at the University of Namibia, located in an arid coastal area where fog is common, allowing the building to catch fog for all of its water needs.

For Portland, Ore., Mithun Architects, Seattle, has created a master plan for Lloyd Crossing. The mixed-use project would include a residential area based on predevelopment ecosystem processes, particularly those of habitat, water and energy regulation.

The fledgling Living Building Challenge, introduced last fall by Jason F. McLennan, Seattle-based CEO of the Cascadia Region Green Building Council, is not as radical as biomimicry, but it is still beyond the norm for most green buildings. McLennan says there are at least 10 planned projects in pursuit of the living building standard, which he says surpasses even the U.S. Green Building Council’s voluntary Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) standard’s highest rating of Platinum. “The Living Building Challenge is attempting to raise the bar and define a true measure of sustainability in the built environment,” says McLennan.

The sustainable building standard is considered compatible with but more sustainable than LEED, the green building rating system that is...

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment