To Todd Harris, trouble at his local bank is a sign of thin times for his building contracting company, J.C. Harris & Sons, which is based in Elgin, Ill., not far from Chicago. Harris keeps an account at Amcore Bank, a mid-sized regional bank, and has even built its branch buildings. But like banks around the world, Amcore reported a loss for 2008: $97.5 million. William McManaman, Amcore’s CEO, told investors that in the last quarter of 2008, builders and developers accounted for the majority of the bank’s new bad loans. So for now, Amcore, like other banks, is about as likely to make new loans for non-owner-occupied building developments as Bernie Madoff is to receive birthday cards from his former clients.

Like other longtime, established building contractors, Harris has seen and survived other recessions. This one reminds him of 1980, with companies bidding in unfamiliar market segments. There is still school and health-care work, but other than that, “I think that the private marketplace has come to almost complete shutdown,” says Harris.

The size of the financial meteorite heading for general building companies will not be clear for years. Banks have pulled back from their already-reduced 2008 level of lending for commercial and institutional construction projects. With a growing number of loans for commercial real estate development in default and banks in need of higher minimum capital reserves, anything real estate-related now is treated as if it could turn rotten. “The lenders are really scrutinizing everyone in the construction industry,” says Ted Bumgardner, vice president with San Diego-based Gafcon, an agency construction manager. It does not matter that home mortgages, not commercial development loans, triggered the financial and economic disaster; it often goes into the same risk pool, industry sources say.

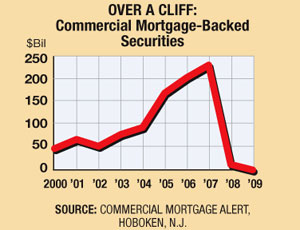

Just as securitization powered the residential mortgage explosion, securitization has underpinned the most recent commercial surge: About a quarter of all commercial real estate loans, totaling roughly $2.5 trillion, are held by investors in commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS). After peaking in 2007 at $230.1 billion, only $12.1 billion of CMBSs were issued last year and none so far this year, according to Commercial Mortgage Alert, Hoboken, N.J.

The problem is the bad hangover from the last few years that has to be worked off. There are hundreds of billions of dollars of real estate loans that must be refinanced, worked out, “de-leveraged,” or written off in the next three years before regional banks will have any appetite for new lending, claims the Urban Land Institute, Washington, D.C.

Dennis Lockhart, chief executive of Federal Reserve Bank in Atlanta, told developers in Miami in February that he is concerned about the potential for CMBS defaults. “Commercial real estate finance challenges could further complicate efforts to stabilize the banking system and credit markets,” said Lockhart. “Banks that financed the construction of commercial properties may end up keeping those loans if the properties cannot achieve the cash flow needed to service new permanent debt.”

About $400 billion of CMBS loans are set to mature in 2009, according to a study by the National Association of Real Estate Trusts. “The loans are coming due, and there is no lending to take out the loans and replace them with new loans,” says Christopher Hoeffel, president of the Commercial Mortgage Securities Association. What this means for the construction industry is that banks will have little interest in writing new construction loans and commercial mortgages until the overhang of bad mortgages is worked out. Under part of the Obama administration’s plan to address the credit crisis, federal funds would be used to boost real estate securities and aid in the sale of CMBSs through traditionally private channels.

There is a similar problem in the bond markets that finance most state and local work, and some hospitals. The collapse last summer of the market for long-term bonds the sector that funds most public capital projects has delayed or killed many projects. Since late last year, the bond market has begun to recover, but new debt issues for capital projects are “slow and expensive,” says Matt Fabian, managing director with Municipal Market Advisors, a Concord, Mass., research firm. “Many issuers are just not going to the market it is tough to get cost-effective market access.”

Most states and municipalities in the market today are focused on borrowing for emergency debt restructuring and short-term funding shortfalls, Fabian says. Longer-term bonds for capital projects are “just a very difficult situation.”

There is a lot of pent-up demand for long-term project bonds, says Fabian, but buyers are “extremely credit-sensitive,” and all but the top-rated issuers have to pay high interest rates. Industry analysts expect bond markets to loosen gradually, but it is not yet clear when.

Meanwhile, commercial developers have started to paste big losses on bank balance sheets. Meruelo Maddux Properties, the biggest private landowner in downtown Los Angeles, says it has stopped making principal and...

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment