Crane Failures Have Industry Looking at Hazards Under the Hook

...material for the application,” says Parnell. He adds that the movement between synthetic slings and fabricated steel can be “deadly.” Softeners, or edge protectors, can keep a sling from rubbing against the load and extend its life.

AP/Wideworld Miami investigation centers on slipped tower section.

|

Under normal circumstances, chain blocks and slings (crane manufacturers typically do not specify the type of sling) would hold the collar during the process, and they would remain in place until the crane is disassembled to act as a failsafe. During the crane-jumping process, the come-alongs also serve a practical need, as workers use the hand ratchets to adjust the height and position of the collar so it can line it up with the strut shoes.

But workers can get in trouble fast in such maneuvers if standard practice is thrown out the window. Poor choices would erode away the strong factors of safety normally built into what normally is a highly engineered task. “This was a recipe for disaster,” says the source.

Workers may overlook rigging because they feel pressure to move the job along by using old, worn out hardware or whatever was available in the gang box at the time of the lift. Whatever the case, “It doesn’t make good sense in human or in dollar cost to cut corners,” says Bradley D. Closson, president of Bonita, Calif.-based CRAFT Forensic Services Inc.

Education Deficit

Employers, too, may put little emphasis on educating workers about the dangers. Today’s culture of corporate safety tends to focus on general accident prevention, such as wearing hardhats and reading material-safety-data sheets. Rigging, though employed by all trades, is often treated like a speciality even though it has the potential to harm many people and damage much property.

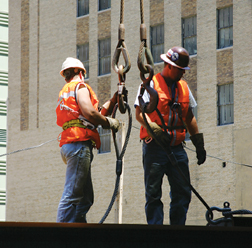

Guy Lawrence / ENR

|

Linton Rigging Gear Supply Smart riggers use edge protectors, or load �softeners,� to keep slings protected (above)

|

Yet construction hangs much of its work on the hook. “A crane cannot make a lift without some sort of rigging,” explains Closson, who has been retained to investigate the New York accident (but is not speculating on causes). He adds that employers in construction need to spend more time on rigging training. “We will beat people to death with reading the Material Safety Data Sheets. We’ll tell them how to lift a box,” he explains. “We’ll talk about ladder safety, holes in decks, electrical tool safety. Then, we’ll talk about slings—maybe once.”

Langford adds that slings come out of the factory with big factors of safety built in, giving workers a false sense of security. Todd Negus, president of Olympic Synthetic Products, Sequim, Wash., explains that nylon web slings are built to withstand five times more weight than their ratings. That makes for super-safe rigging devices, Langford notes, but he says it creates a potential hazard: “It’s easy to overload it without breaking it. And that leads people to develop bad habits.”

Rigging failures also are often the result of neglect. In a West Coast accident that Parnell investigated in 2005, a contractor rigged two web slings in basket hitches to lift a 19,000-lb skid. One sling broke at the eye, dropping the load. No one was hurt, but a factory pull test on the other sling found that it snapped at 50% of its design strength because it was already faded and overused. Even so, the slings might have scraped by without breaking. One sling broke because the hook was previously damaged from steel hardware, creating a razor-sharp edge.

Makers of lifting slings—nylon web, polyester roundslings, chain and wire rope—say those safety factors protect them from liability, as workers tend to abuse the gear. But construction is extra rough on rigging, especially soft slings. “Normally, they beat the crap out of the sling, then put a surge on it,” says Parnell.

| + click to enlarge |

Chart: Industrial Training International INC |

Synthetic slings are especially hazardous when wrapped around hard materials, even when some edges don’t look sharp. “Cutting is related to weight or force,” Closson explains. “We learned this basically in the third grade, when Mom brought out the stick of butter that was in the refrigerator rock hard. You took a knife and tried to cut it. The harder you pushed, the more it pushed through. People will look at a piece of angle iron, run their hand across it, come back without a bloody stump and think it is OK.”

Manufacturers, such as Sellersburg, Ind.-based Linton Rigging Gear Supply LLC, make edge protectors that help prevent cutting.

Its magnetic wear pads cost about $700 for a set of four. “Even though my softeners are expensive they pay back what you save on slings,” says Ray Linton, president. Chain and wire rope slings should also be protected, he adds.

Rigging may seem like an easy job, but it is best left to those who know what they are doing. Calculating load capacity, center of gravity and hitch angle should be done under the supervision of an experienced crew member because carelessness and ignorance leads to mistakes. Training can make the difference between a safe lift and a disaster: “There are three to five good ways to rig almost any load,” says Parnell. “And two or three bad ways.”