For more than 140 years, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Galveston District has tackled massive projects to provide safety and stability along a coastline stretching from Louisiana to Mexico. The scope of its efforts runs nearly as long as its history, including flood risk mitigation, ecosystem restoration, shoreline protection, navigation, military construction and emergency management services.

That proud—and increasingly crucial—tradition is continuing with three endeavors the Corps is currently overseeing: the Sabine Pass to Galveston Bay Coastal Storm Risk Management (CSRM) project; Buffalo Bayou and Tributaries Study and the Coastal Texas Study.

While the projects’ scopes are different, their goals are the same: to provide stability and safety across the 50,000-sq-mile district.

Fred Anthamatten, a senior adviser at Dawson & Associates, a Washington, D.C.-based firm that focuses on federal water issues, says that key tenets of the Corps in the Sabine Pass to Galveston Bay project are safety, economics and the environment. He previously spent 35 years working at the Galveston Division, including seven as head of its regulatory branch and 13 as head of enforcement.

Anthamatten notes the project “certainly takes into account the safety of the residents, enhances and protects the economy and thirdly, and no less importantly, protects the environment,” he says.

For leading these initiatives, ENR Texas & Louisiana recognizes the Corps Galveston District as its 2023 Owner of the Year.

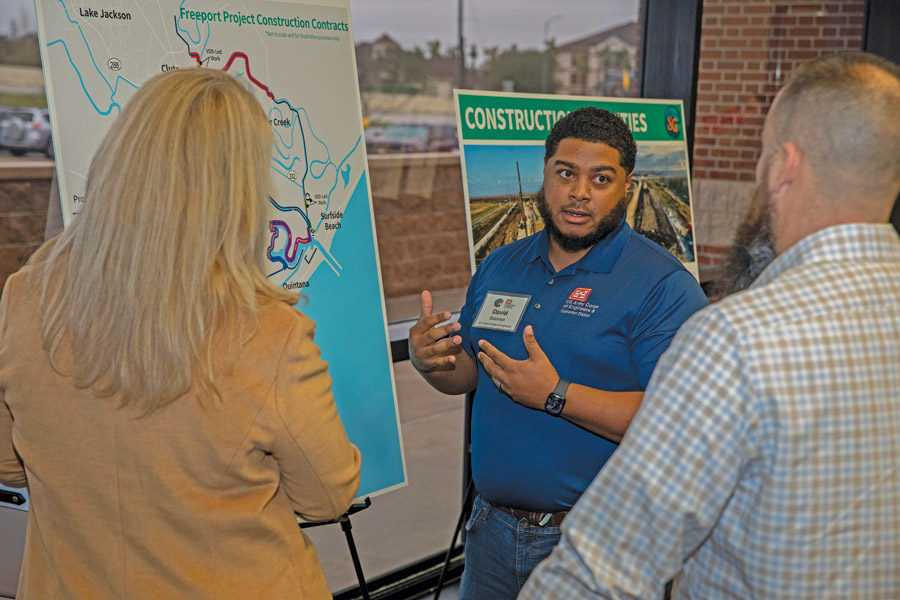

David Solomon, civil engineer with USACE’s Galveston District speaks with an attendee at a recent public open house about components of the Sabine Pass to Galveston Bay (S2G) Coastal Storm Risk Management Program.

Photo courtesy of the Galveston District of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

Megaproject

The district’s trio of important efforts starts with its Sabine Pass to Galveston Bay Coastal Storm Risk Management project. When completed—at a still-undetermined date—the impact of this estimated $4-billion effort will be felt by nearly everyone, says Maj. Ian O’Sullivan, deputy commander of the megaprojects division. He outlined the project’s four major objectives as decreasing risks to human life from storm surge impacts; reducing economic damages to communities; enhancing energy security by reducing storm surge risk to petrochemical facilities; and reducing adverse economic impacts on waterways used for commercial and recreational purposes.

The project is divided into three elements: the Orange County CSRM, the Port Arthur and Vicinity CSRM and the Freeport and Vicinity CSRM. The Orange County CSMR, itself estimated at $2.4 billion, will construct a coastal storm surge protection system consisting of 26 miles of levees, flood walls and pump stations that begin near the intersection of Interstate 10 and the Sabine River.

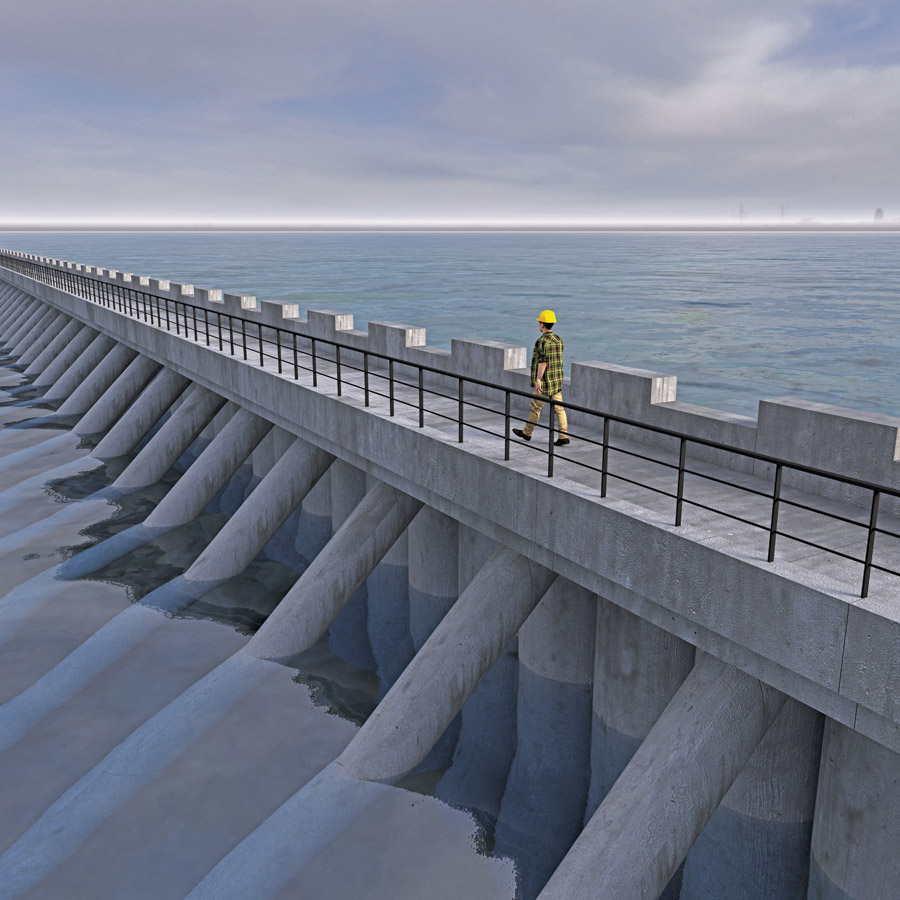

A massive seawall is one concept being considered to protect Galveston Bay.

Rendering courtesy of the Galveston District of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

“It then will proceed south and southwest generally along the alignment of the Sabine River, and then westward around the city of Bridge City and terminating southwest of Orangefield,” explains O’Sullivan.

Additionally, the $863-million Port Arthur and Vicinity CSRM will construct about six miles of earthen levees, six miles of floodwall and 26 vehicle closure structures.

Robert Thomas, chief of the Galveston District’s engineering and construction division, says the objective is to “increase the level of performance and resiliency of the existing Port Arthur and Vicinity Hurricane Flood Protection project in Jefferson County.”

The Freeport and Vicinity CSRM, located in nearby Brazoria County, will raise around 13 miles of the existing levee system, build approximately six miles of floodwall and install a navigable lift gate in the Dow Barge Canal, says Thomas. That project’s cost is estimated at $704 million.

“It certainly takes into account the safety of the residents, enhances and protects the environment ... and no less importantly, protects the environment.”

—Fred Anthamatten, Senior Adviser, Dawson & Associates

The megaprojects are not without issues. While high inflation rates are impacting material prices, the recent injection of federal infrastructure funds is exacerbating the issue of rising construction costs.

“To help offset increasing construction costs, USACE is committed to partnering with the construction industry to help identify innovative solutions to reduce cost while providing greater benefits to the residents that rely on these critical coastal storm risk management projects,” O’Sullivan said in a statement.

The Corps has always been an engineering innovator. On the Sabine Pass to Galveston Bay project, it is implementing an early contractor involvement (ECI) method to keep costs down while constructing better projects.

Thomas explains that with the ECI purchase delivery approach, the federal government holds separate contracts for design and construction.

“The construction contractor collaborates with the design engineer, the Corps and our non-federal sponsor providing preconstruction services—cost, schedule, constructibility—which are intended to optimize the cost, schedule and utility of the project,” he says.

After hosting public forums and other outreach efforts, the Corps says it believes area residents welcome the project. One way the Corps kept the public informed of developments was through the use of ArcGIS maps, which allowed the public to stay informed without attending public meetings due to COVID-19 restrictions.

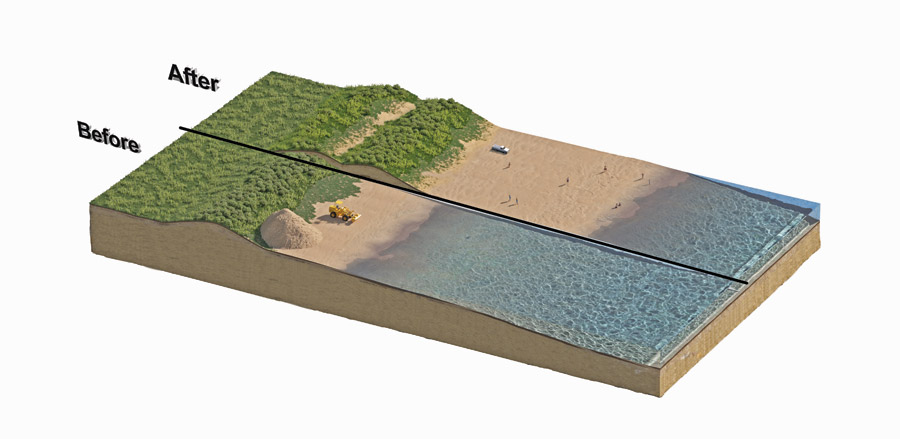

This rendering illustrates how beach dunes could be restored as part of the Coastal Texas program.

Rendering courtesy of the Galveston District of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

“They understand and fear the risk of storm surge and hope the work of this program will protect their lives as well as their livelihoods,” Thomas says. “The full range of impacts is still under analysis, but potentially they will see a change in the natural flow of drainage in areas near the protection and a change to available access routes to the Gulf.”

In 2017, Hurricane Harvey ripped through Houston and surrounding areas, causing billions in damage. Since then, several other floods have caused evacuations in the Houston metropolitan area, the largest in Texas. A year later, the Corps started its $7.8-million Buffalo Bayou and Tributaries Study.

The study’s goal is to “reduce life safety risks, reduce flooding risks and damages, and to support the community resilience and recovery,” says Gretchen Brown, Galveston District project manager.

Part of the study includes examining ways to ease risks for communities along the Buffalo Bayou and its tributaries, both upstream and downstream from the Corps-operated Addicks and Barkers dams, she says.

About a decade ago, the nearly 80-year-old dams’ outlet structure was identified as a primary risk. To address this, engineers created a plan for seepage cutoff walls and new outlet control structures.

Before a recommendation is delivered, the research team is examining the best scientific and technology available to ensure the two dams are “designed, operated and maintained as safely and effectively as possible into the future,” the Corps says.

A deadline for the study was not available from the Corps.

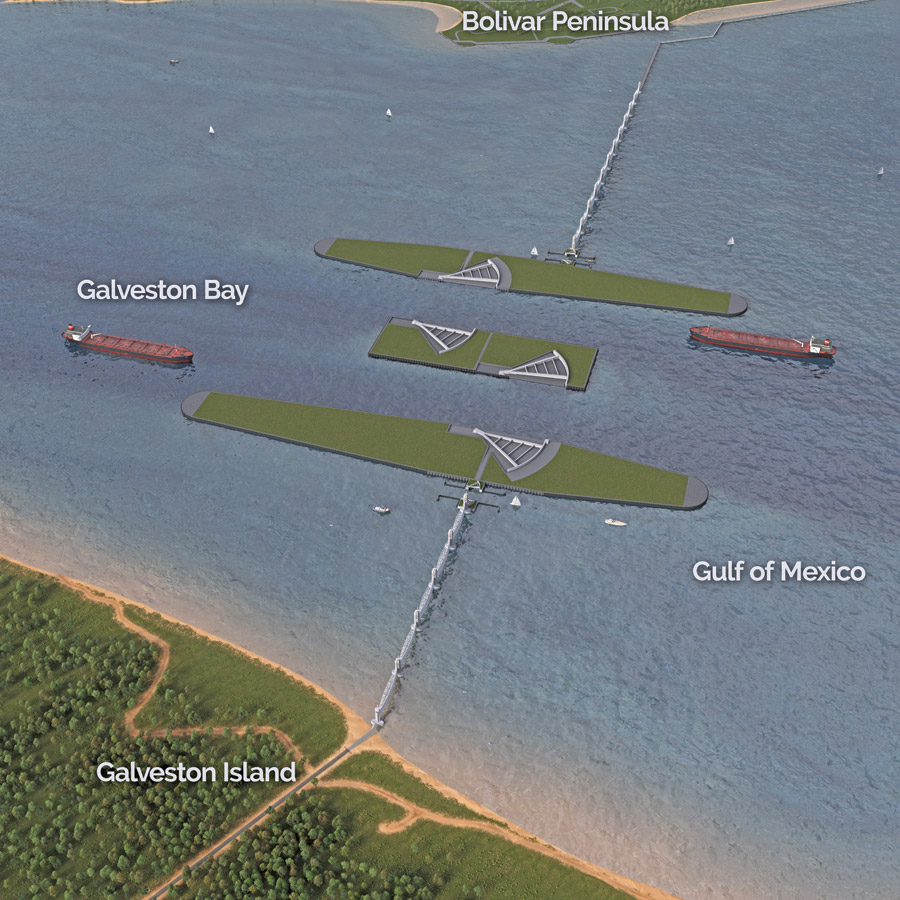

An aerial view of the Bolivar Roads Gate System that would be implemented in Galveston Bay as part of the Coastal Texas program.

Coastal Texas Study

The final report for the District’s Coastal Texas Study, released in 2021, dubs the effort’s focus as a “multiple lines of defense” strategy. The study’s origins date to 2008 when Hurricane Ike ripped through the upper Texas Coast, a region that includes petroleum facilities in Beaumont and Port Arthur. The study focused on decreasing public health and economic risks, restoring fragile ecosystems and advancing coastal resiliency. The Corps estimates total implantation of these strategies at more than $28 billion.

When finished, the $20-million study made several suggestions on how to achieve those goals.

Gulf defenses center on redundancy and robustness, accotding to the Corps. The first objective is to keep storm surges in the Gulf of Mexico. Its plan calls for “a combination of surge gates … seawall modifications on Galveston and dune and beach systems on Galveston Island and Bolivar Peninsula,” the Corps says. But those improvements will not solve the problem. The report continues that “a combination of water from Galveston Bay and Gulf surge that could overtop the front-line defenses must be addressed through a second line of defense.”