Set in a remote wetland area in west Salt Lake City, the new Utah State Correctional Facility is nearly complete. Five years ago, birds and mosquitos and acres of grazing land held sway in this once undeveloped area in the city’s northwest quadrant.

Now six miles of new roads provide access to the 230-acre construction site for what will be the largest detention facility in Utah. Designed to house up to 3,600 inmates, the 32-building, 1.3-million-sq-ft complex cost nearly $1 billion to build. The project broke ground in 2017 and is set to be completed May 20. At its peak, the project maintained 1,500 workers on the site, with 10,000 workers involved in total.

“This was a greenfield project, approximately two miles off the nearest paved road, so we had to construct a road just to access the site,” says David Whimpey, vice president at Layton/Okland, the joint venture contracting team for the prison.

Walls were made of 30-ft by 35-ft concrete sandwich panels, assembled flat on the ground and then tilted into place with a crane.

Image courtesy State of Utah DFCM

Michael Ambre, assistant director of the Utah Division of Facilities Construction and Management, has been involved in the project since its beginning, when the state bought the 300 acres in 2016 to replace the current 1950s-era Utah State Prison in Draper. The site presented numerous challenges with its remote location, sensitive environment and problematic soil.

The project team worked closely with the National Audubon Society to manage any environmental issues, including the presence of a nearby bird refuge as well as tundra swans, bald eagles and long-billed curlews. The team also hired a biologist to walk all 300 acres every four days with a dog to sniff out any burrowing owls, a process that went on every summer for years. Fortunately for the project, the owls discovered weren’t nesting and so could be relocated.

Designing and installing the prison’s complicated and often redundant utility grid offered some of the project’s biggest challenges, Ambre says. The project required an extra power feed along with two substations. In addition to six miles of new roads, the team installed 11 miles of sewers and two separate water lines extending three and four miles long.

At its peak, the project required 1,500 workers on the remote site, with 10,000 workers involved throughout the project.

Image courtesy State of Utah DFCM

All this new infrastructure was not only built to support the prison but also includes the capacity for future expansion and development, Ambre says. A partnership with developer Northwest Quadrant LLC helped with that process, coming to the table with about $12 million in new funding to increase the capacity of utilities. Three large developments have sprung up nearby, with plans to create millions of square feet of warehouses as well as a proposed truck stop and rail spur for a possible inland port.

Then there’s the soil itself. “It’s not technically wetland, but it is a collapsible soil, so obviously the foundations are tricky,” Ambre says. The project team used surcharging and wick drains to manage the soil and trucked in 3 million tons of fill material to help stabilize the site.

The highly corrosive soil also was a danger to any metal pipes or infrastructure placed underground, Ambre says. The team installed a “cathodic” system that energizes any metal component with a small, constant electric charge to combat corrosion.

The prison will house all four classifications of inmates, with separate facilities for men and women.

Image courtesy State of Utah DFCM

The flatness of the land and its high water table—located about 4 ft below the surface—affected the sewer design, he said. While the city at first preferred the more familiar gravity-based sewer systems with easier maintenance, officials approved the construction of pumping stations because of cost (a gravity-based system would have required digging down about 35 ft, with extensive dewatering) and issues stemming from a nearby closed, unregulated landfill.

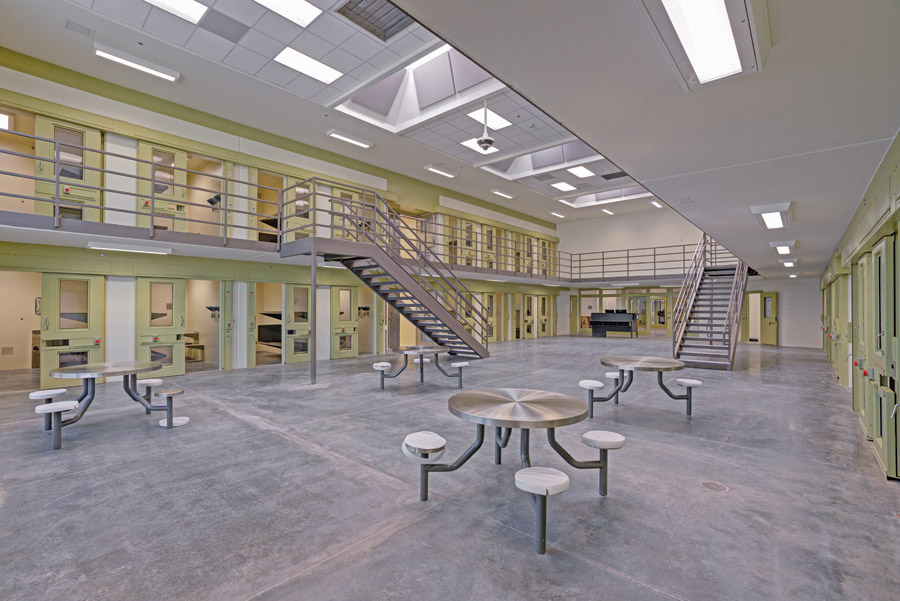

The detention facility’s design also presented challenges because it will house all four classifications of inmates, with separate facilities for male and female inmates, ranging from maximum security to the general population. The cells range from one-person to eight-person capacity, and there are dormitories made of “cubicles” with 4-ft walls. In this design-assist project, individual buildings often followed their own construction schedules, Ambre says.

“Instead of having a continuous flow from one end of the project to the other side, we ended up having various locations with work going on.”

— David Whimpey, Vice President, Layton/Okland JV

“We had various buildings in various stages of design, and I needed consistency throughout the site—for fire alarms, for security electronics and for building management systems and locks, for example,” Ambre says. “But how do you bid the entire package for all 1.3 million square feet when only two buildings are finished from a design standpoint?”

The team ended up treating the project’s competitive bidding and procurement process like a puzzle, keeping track of different buildings at different stages, requiring detailed, transparent bids. When the maximum-security building went out for bid, for example, the company that won its security-electronics package did the same work for the other buildings as well. In the end, about 53 bid packages were issued, and the project used more than 400 subcontractors, Ambre says.

Designed to hold 3,600 inmates, the facility includes 1,000 precast cells.

Image courtesy Layton/Okland JV

The project’s order of work changed as designs were completed and bid packages became available to bid out the work, Whimpey says. “We ended up shifting and doing what we could do to maintain progress going forward and getting creative,” he says. “For example, we had planned to start from the northwest corner with the male general population building and work kind of diagonally across the project to the southeast corner. Instead, we started with the male maximum security building, and then from there, it kind of started bouncing around a little bit.”

The site quickly became a complicated puzzle, with a warehouse, correctional industries and the women’s campus building starting work. “Instead of having a continuous flow from one end of the project to the other side, we ended up having various locations with work going on,” Whimpey says.

Access became an issue, with staging areas and casting beds for the concrete wall panels taking up space, Whimpey says. “We had utility work that was going on through the site. We had deliveries coming to adjacent buildings. We had precast prison cells that were coming. I think at one point we had up to nine large 348 crawler cranes on the site in addition to smaller ones.”

Detention cells can hold from one to eight inmates. The design also includes dorms made of “cubicles” with 4-ft-high walls.

Image courtesy Layton/Okland JV

The team tamed the busy site with communication and coordination, ensuring that crews’ deliveries, access and scheduling worked together. “While it wasn’t maybe an ideal scenario or planned that way, we were able to compensate and adjust our plan and site logistics and make it work,” Whimpey says.

The buildings were constructed with 30-ft by 35-ft concrete sandwich panels, assembled flat on the ground and then tilted into place with a crane, Ambre says. The “sandwich” was comprised of a 3-in. section of architectural concrete, another 3-in. section of rigid insulation and a concrete slab. Each panel needed to accommodate the extensive electronic and security systems.

“You sort of have one chance to get all the conduit and all the pathways put into that panel prior to it being poured,” Ambre says. “We had to redo a few of them.”

In March 2020, two unexpected events hit the project at once: the COVID pandemic and a 5.7-magnitude earthquake. With the epicenter only a few miles from the site, a number of braces holding up concrete wall panels broke, and some panels shifted in place, with minor cracking, Whimpey says. The quake had little impact on the project and caused no safety issues, but the pandemic continued to affect the project’s supply chain.

The new facility includes flexible spaces for inmate treatment, rehabilitation, education and job training.

Image courtesy Layton/Okland JV

“The supply chain was changing so quickly that we went directly to the heads of several manufacturers to work out our product supply,” Whimpey says. In 2021, a paint shortage prompted the team to reach out to neighboring states, and one project was completed using about 700 1-gallon buckets of paint because larger bucket sizes weren’t available.

The prison project is now on track for a May completion date thanks to a mild winter that allowed sitework to continue through those months. Construction is 94% complete, says Ambre, with one building still under construction, and crews are finishing the project’s more than 10 miles of fencing as well as site gates and landscaping.

A sitewide blackout test is scheduled in the next few weeks to test the power system—with both lines going down as might happen during a natural disaster, for example. The testing team will cut the power, turn on the prison’s four generators (which can produce a total 10 MW of power) and then shut down the generators one by one to test critical systems.

With its freshly laid roads and utilities, as well as multiple buildings and electrical substations, this project is more than a detention center, Ambre says. “It’s actually a small city for 7,000 people.”

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment