The bustle of traffic returning to Manhattan’s FDR Drive as COVID-19 lockdowns end has an unlikely mirror image out on the nearby East River, where crews on nearly two dozen barges are drilling bedrock, ferrying concrete and lifting precast deck and bridge pieces for a $100-million effort to construct an elevated 1.8-acre park with new bike and pedestrian paths on the water.

The East Midtown Greenway will extend for 2,000 ft on a deck atop the river from East 53rd to East 61st streets, hitched to land on the south side by a 114-ft-long pedestrian bridge and by a ramp structure on the north. The project is a major link in the city’s goal to complete a bikeway-pedestrian path network circling Manhattan, with some portions complete and future sections pending.

Led by the New York City Economic Development Corp. (EDC) as owner, Stantec as structural engineer and Skanska USA Building as construction manager, the project started in November 2019. It’s now a giant synchronized swim of materials delivery and construction tasks on the way to completion in summer 2023. Other team members are KC Engineering and Land Surveying, Mott MacDonald, Rosales + Partners, Marine Infrastructure Engineering Solutions and AKRF Inc.

The in-water activity owes partly to heavy use of precast concrete, with up to 20 barges floating in place last year, says Robert Reid, senior project manager at Skanska. “We’ll probably have more this year,” he says.

Precast was a value engineering call to reduce dependence on cast-in-place concrete because of difficult site access and the need for long pumping lines up to 2,000 lineal ft or barged-over buckets of premixed concrete, Reid says. Because precast weighs more, the barges carry cranes of all sizes—including several heavy lift units—to hoist massive deck pieces, caissons, pile caps and bridge sections, he says.

Workers are catching up after the pandemic and fish migrations occasionally paused the project.

Photo by Stantec

The barges also supported early marine demolition to remove an old waterside platform and timber piles, and to yank out steel reinforced concrete piles installed 15 years ago for a temporary outboard roadway that detoured traffic for an FDR Drive rehabilitation. The Greenway team opted to not retrofit and raise those caissons because that would have required more work and cost than removing them, says Amy Seek, design director for Stantec’s New York landscape design team.

“The steel that remained was not going to give the capacity for the beautiful landscape in our design,” she says.

Crews on barges also erected a sheet pile wall securing FDR Drive. They continue drilling for a variety of piles, with diameters of 30 in. to 60 in. and lengths down to 130 ft, and spacing from 40 ft to 95 ft apart—all depending on the riverbed elevation and size of the deck, which supports a 40-ft-wide esplanade in most sections. The Greenway caissons are all socketed into rock with reinforced concrete and precast caps, but there are also 56 driven caissons at Andrew Haswell Green Park, for a total of 143 in-water caissons and upland micropiles on the project, Reid says.

Pile-driving has been smooth for the 30-in. piles in shallower bedrock but has been more challenging for the 54-in. and 60-in. piles because of the depth and subsurface obstructions, says Kathryn Prybylski, EDC vice president in its capital program.

“The in-water drilling is the thing with the most unknowns, even with the robust geotech program we used to test bedrock,” she says. While work resumed last summer after the state’s pandemic shutdowns, in-water activity must pause annually from late March to late June to protect migratory fish, Prybylski says.

The team now is focused on the remaining pile-driving and caisson installation before the next moratorium, she adds. “We hope to finish all of that drilling before the end of next March so we can do the rest of the deck work in 2022 and into 2023,” she says.

The Queensboro Bridge, which connects 59th Street in Manhattan to Long Island City in Queens, is a picturesque backdrop for the future park.

Photo by Stantec

Three Phases

While the eventual 32-mile pathway around Manhattan has major legs complete such as the 11-mile west side Hudson River bike path, the new section is notable because it is mostly in the water. The city in April announced $723 million in funding to complete the rest of the ring by 2029.

Features such as the in-water structure, a topside park, the connecting structure to Andrew Haswell Green Park at 61st Street and ADA-accessible pedestrian bridge to Sutton Place Park at 54th Street are bringing together the city’s Dept. of Transportation and Dept. of Parks, with EDC as the lead agency, Prybylski says. While the city announced financing for the Greenway portion in 2017, an earlier budget allowed the team to start early permitting efforts with the state Dept. of Conservation, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, National Marine Fisheries Service and U.S. Coast Guard.

With some early approvals in hand, the EDC chose Stantec in a 2017 request for proposals, the same year some Skanska teams came on board. “We were able to get their input on constructibility concerns and cost estimating early as we got into procurement,” Prybylski says.

A sheet pile wall securing FDR Drive was placed by crews on barges.

Photo by Stantec

The design team coordinated with DOT, which will maintain the pedestrian bridge, and the parks department, which will take over Andrew Haswell Green Park, says Olga Gorbunova, a Stantec principal in New York. “We worked closely with those agencies to develop the design criteria,” she says.

Construction is progressing in three phases—the first focused on the northernmost section, the second from about 58th to 55th streets and the last on the southern portion, Reid says. First phase in-water work is nearly complete, which will allow the team to finish installing the deck and focus on topside landscaping, pathways and railings, while marine efforts continue on the other phases. “We’re going to chase the water work down the river with the topside work,” he says.

Throughout construction, the team has adjusted for the coronavirus, requiring masks on site and bringing in extra work trailers, Reid says. “That helped us get through,” he says. “We had no COVID outbreaks on the site.”

The project team also has been in frequent contact with civic leaders and responsive to questions, says Barry Schneider, who chairs a projects committee for Community Board 8. His group’s main concern was the link to the park at 61st Street, aiming to ensure the Greenway does not limit future plans to build out the facility and an old marine terminal on site, he says.

“We want to make sure that the completion of the park and the interior of the building meets the needs of the community,” Schneider says.

When completed, the East Midtown Greenway will add to the bike and pedestrian path network that will eventually circumnavigate Manhattan.

Rendering by Stantec

Topside Heavy

The Greenway’s design had multiple goals from the outset, such as meeting requirements to minimize height and shading over fish habitats as well as to limit the structure’s visible bulk while still allowing a multifaceted park on the water, Gorbunova says.

“We had to find a better geometry and efficiency for the structure to minimize concrete and increase the design aesthetic,” she says. The result in part involves using top girders with angled profiles and angled parapet walls to create a slimmer profile, but also to allow the deck to accommodate ample planned landscaping and programming for the linear park.

Another major concern was ensuring the structure could not only support its own weight—including topsoil for trees and the potential load of ambulances—but also impacts from seismic, wave, wind and flood events, Gorbunova says. The top of the deck is set about 12 ft over the river high tide elevation to account for a 3-ft rise in sea level by the year 2100, she says.

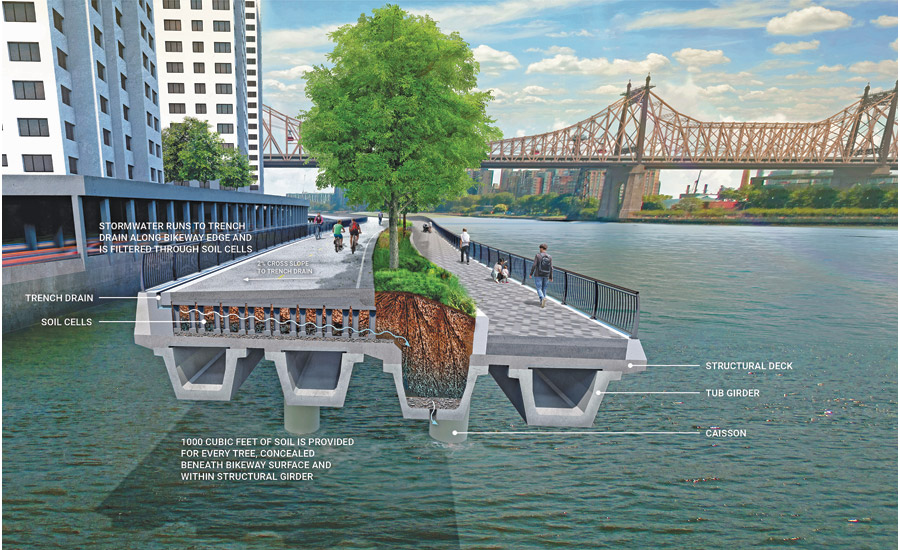

Gorbunova early on brought together multiple project participants to discuss design issues, which helped team members better understand their varying challenges and needs. That directly led to solutions for locating 1,000 cu ft of topsoil for each of the 60 trees on the deck and a stormwater catchment to irrigate the trees and other plantings, Seek says.

The design incorporates space for the soil within the structural tub girders, which will allow roots to spread laterally, and trench drains along the edge to capture stormwater, she says. “It was a way to hold onto the water for as long as possible so the roots could use it,” Seek says.

Using concave U-section girders allowed for the soil to be recessed within the structure, Reid says. “Those top girders also allow us to span further distances, from 80 to 95 ft,” he says.

The southern portion of the structure will have a section that can be removed and reconstructed for the city to continue the in-water park to the south, Seek says. “We have a piece that cantilevers to the south so that a new section can land on piles,” she says.

The design incorporates space for soil within the structural tub girders, and trench drains will capture stormwater to irrigate the roots of the park’s 60 trees.

Rendering by Stantec

Outstanding Work

Big remaining tasks include the connection to Andrew Haswell Green Park and the 54th Street pedestrian bridge. The work on the north side includes a transition platform that ramps up and out 30 ft from land over to the esplanade, Prybylski says. Many planks for that outboard section are already in place in the first phase section, she says.

Installing the 100-ton pedestrian bridge, expected late this year or early in 2022, is a bigger challenge because the crane could not span over the FDR Drive, requiring a barge lift, Reid says.

“The closest we could get is 200 feet, so we’re using one of the largest cranes in the harbor,” Reid says. “It’s not extremely heavy, but that’s a long reach.” The bridge to link Sutton Place Park to the Greenway structure is being fabricated in Nova Scotia with pieces assembled in Brooklyn and barged upriver, then lifted into place in one overnight shift, he says. Work just began on the bridge abutments.

The bridge placement will require a scheduling “dance” for a time because the team needs room for barges and thus can’t install all of the caissons for the southern esplanade until the span is in place, Prybylski says.

The Rosales + Partners-designed bridge also aims to meet community requests to minimize the size of the landing and ramp in Sutton Place Park, Gorbunova says. “We worked hard to find a structural system with minimum depth of the superstructure,” she says. “That’s the tied arch design … It’s functional and beautiful.”

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment