Geothermal heating and cooling aren’t new to New York City office buildings, nor are thermally activated floor slabs, dedicated air ventilation units or even all-electric HVAC systems. But only one building ties all these advanced sustainable technologies together—the 270,000-sq-ft, 16-story 555 Greenwich St. in lower Manhattan, which broke ground in September 2020 and aims to open early next year.

The slender structure, on a lot that housed a one-story car park in Manhattan’s Hudson Square, has ambitious objectives: achieving LEED Platinum status, slashing typical spec office development carbon emission levels by avoiding use of fossil fuel energy sources and connecting through portals on most floors to neighboring 345 Hudson St.

The project team—led by Hines, Trinity Church Wall Street and NorgesBank Investment Management as developers; COOKFOX as architect; AECOM Tishman as construction manager; Thornton Tomasetti as structural engineer; and Jaros, Baum & Bolles as MEP engineer—has set tall sustainability goals.

The project aims to beat the city’s 2030 carbon emission targets by 46% and meet its 2050 carbon-neutral goals. It also will reduce electricity consumption by 29% compared with traditional systems and use high-end ventilation technologies to optimize indoor air quality, a key priority for tenants after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Getting Out Ahead

Such goals called for a willingness to invest in new technologies, with the developers aiming to exceed the city’s Local Law 97 sustainable design mandates, says Rick Cook, COOKFOX founding partner.

“It’s an interesting time for our city … with incredibly aggressive carbon reduction goals,” he says. “[The developers] sat down, took a deep breath and said, ‘Let’s get out ahead of it.’”

The project team soon realized that linking independent technologies could ultimately deliver an all-electric structure, Cook says. “It took leadership to weave these things together and to take known technologies to a level nobody had done in New York,” he claims.

The combination of advanced sustainable concepts led to other opportunities, such as reusing waste energy from chilled water systems to power heat pumps, says Mike Izzo, vice president for carbon strategy at Hines. “We were able to use the efficiencies of one system to benefit the other,” he says.

Jaros, Baum & Bolles has had experience with similar technologies, but not applied cohesively in a speculative office building development, says Michelle DeCarlo, associate partner at the engineering firm. “We’ve never put them together like this,” she says.

Other design choices had similarly symbiotic benefits, such as forgoing a large cellar in favor of a higher-elevation basement slab to achieve better flood protection, says Jeff Callow, Thornton Tomasetti principal and project lead. That decision led the team to use caisson foundations, which in turn will provide more predictable settlement of the structure and an optimal setup for the geothermal system, he says.

“There were a lot of deliberate decisions that involved thinking about the whole life cycle of the building,” Callow says. “Their vision looked for the benefits for the building in the long run.”

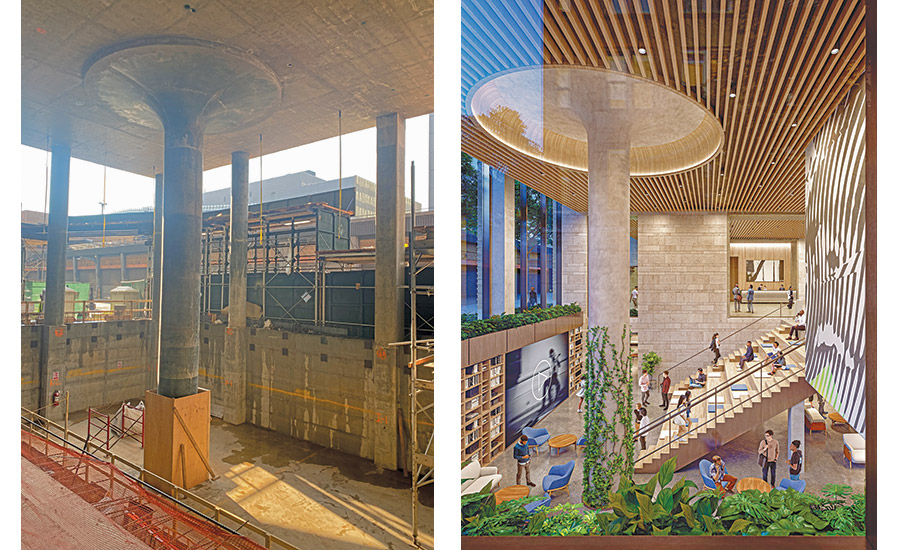

Before and After: The 555 Greenwich St. project team plans to turn a structural necessity into an aesthetic feature of the building’s lobby.

Photo (left) by Hines; Rendering (right) by Hines and Cookfox

Strong Connections

The project’s other signature feature is more visible: seamless connections on a dozen office floors between 555 Greenwich and its 345 Hudson neighbor, owned by the same joint venture. Linking the structures offers larger floorplates and more space configuration flexibility to tenants, better building functionality and enhanced value for both properties, Cook says.

“The whole is greater than the sum of the parts,” he says. “The two are able to coexist but also interconnect.”

The opportunity to boost the utility of 345 Hudson—which may also get upgrades—was appealing, Izzo says, noting that “extending the use of the building next door also benefits the neighborhood and offers connectivity to the waterfront.”

Work to connect the two structures entails preparing 77 possible portals between column bays on each office floor—42 on the six lower podium levels and 35 on the seven slimmer tower floors, 10 through 16. But the project team will only carve out the connections where tenants have signed up to lease a space that straddles both buildings. In spaces not linked upon the building’s completion, future tenants still will have the option to open the already prepped portals if they wish to lease a space across the larger two-building floorplate.

Work is progressing on the effort, which has a $185-million construction budget. After design work began in April 2019, the team conducted demolition in summer 2020, followed by excavation and foundation work in September. Above-grade construction started in September 2021, and exterior work on the podium’s masonry and punched windows facade and the tower’s glass and steel curtain wall began in November.

The team now is erecting the concrete superstructure on upper floors and facade on lower floors. Curtain wall installation starts next month, with topping out slated for April, full enclosure by October, substantial completion early next year and tenants arriving in spring 2023.

Various technologies will contribute to 555 Greenwich’s sustainable performance such as high-efficiency plumbing and wastewater recycling systems that will save 800,000 gallons of water annually and the use of recycled rebar, concrete and glass.

Rendering by Hines and Cookfox

Highly Sustainable

Varied technologies will contribute to 555 Greenwich’s sustainable performance, such as high-efficiency plumbing and wastewater recycling systems that will save 800,000 gallons of water annually as well as the use of recycled rebar, concrete and glass.

But the biggest boost is from innovative elements, such as the geothermal system that will supply 30% of the cooling load and 40% of heating by sending liquid glycol through tubes deep underground, raising or lowering its temperature depending on the season and recirculating the acclimated fluid up into the building, where it also runs through air source heat pumps on the roof.

“The building will capitalize on using the geothermal system as its first source of energy because it’s free energy from the ground,” DeCarlo says.

Another pioneering feature for office buildings is thermal storage within the concrete superstructure, which involves pipes circulating and reusing waste energy water as well as the radiant floor system. The flooring, which uses 20% less energy than traditional forced air vents and fans, offers more thermal comfort within tenant spaces because chilled or heated water travels through piping loops built into the floor slabs, better distributing desired cooling or heating levels, DeCarlo says.

“Radiant flow is one of the most energy-efficient solutions,” she says.

The building also is using dedicated outdoor air systems, or DOAS, to bring in large amounts of pure outside air through multiple intakes on each floor, with similarly dispersed chambers removing exhaust air. That avoids spreading contaminants across a building, which occurs in central HVAC systems that recirculate internal air for ventilation. Locating the DOAS units on each floor also uses less energy because the air travels shorter distances.

In tandem, the building has an advanced sampling and monitoring system to check indoor and outdoor air quality for volatile organic compounds, large and small particulates and carbon dioxide. It automatically adjusts air delivery in the DOAS units to limit pollutants.

Above-grade construction started in September. Exterior work on the podium’s masonry and punched windows facade and the tower’s glass and steel curtain wall began in November.

Photo by Hines

Engineering Challenges

Integrating all of these technologies entailed an extensive engineering effort. The geothermal system offers a prime example. Once the design called for a higher elevation basement floor—with a pressure slab and caissons drilled down 80 ft into bedrock to support the foundation—the building also ended up with an efficient framework for the system, allowing its tubing to run down every caisson across the site rather than in a single loop, Callow says.

“Having those caissons drilled down to rock and embedding these loops in it was a benefit; we wouldn’t have had that with a mat foundation,” he says.

But to make the system work with a pressure slab, the team also created a trench in the middle of the footprint that hooks up to all the geothermal loops, simplifying connections to the building systems above and allowing for easier maintenance and updates, Callow says. “From a structural perspective, the trench offers a lot of flexibility for future MEP work,” he says.

The developers also brought in geothermal contractors and consultants early in the project, which aided the design and deep foundation work, according to Callow. “It’s helpful to have that expertise available when you have a unique system,” he says.

The building also has air source heat pumps located on the roof, similar to a cooling system’s chiller plant, which generates heat by using electricity to run compressors and removes the need for a gas- or steam-powered boiler, DeCarlo says. That system also ties into the geothermal infrastructure, using its output to reduce the amount of chilled or hot water needed for the air source pumps to operate. But with air source heat pumps not common for New York City office buildings, the JB&B team went directly to the manufacturer to ensure the technology was suitable to the building’s needs, she adds.

“We needed to see how it would perform in our climate and [conditions],” she says. “We pushed them to do testing to show us the performance.”

While 555 Greenwich St. was designed before the COVID-19 pandemic, its amenities that focus on fresh air, outdoor spaces and creating a healthy workplace are in demand today.

Rendering by Hines and Cookfox

Married and Separate

The horizontal connections on tenant floors was another engineering challenge, especially around the new structure’s natural settlement over time, according to Izzo. The buildings have seamless connecting portals on every tenant floor but stand up to 6 in. apart to account for seismic risk, he says. “There were intentional steps in our carving of the form of the building to integrate them,” Izzo says.

Accounting for differential settling was another reason caissons were an optimal choice, Cook explains. “We knew we wanted to have the floors align perfectly,” he says. “We could have done friction piles, but there is a high degree of stability in the floor levels using caissons.”

But even with caissons into rock, some settling, albeit more predictable, will occur, which led to the decision to put a topping slab on each floor of 555 Greenwich, Callow says.

“Even with the best analytical tools, you needed some [flexibility],” he says. “It was a way to smooth out the transitions between the buildings.”

In tune with the building’s synergetic theme, that extra 5 in. of concrete slab also served other purposes: It houses the radiant heating and cooling tubes traversing the floorplates and includes a notch along floor perimeters to help install the curtain wall’s glass panes more easily and securely, Callow says. The topping slabs also offer tenants the ability to choose their own custom flooring finishes, he adds.

The flow between the two neighbors extends to 555 Greenwich’s ground floor, giving each building additional entrances and street access, with the new lobby serving as a westward-facing piazza for the joined structures that opens to a view of Greenwich Street, Fox says.

A relationship with the outside permeates the lobby design, which avoids a conventional bank of elevators squared off against each other and instead has them open facing the cityscape alongside an exposed staircase—features that also serve to reduce congestion in the space. “It’s not buried in a conventional core,” he says.

The lobby design also sculpted a large column, which rises from the lower level to hold up the second-floor slab, into a signature visual feature, Fox says. “It reminds you of a lily pad in a pond,” he says.

A final affirmation for the developers’ vision is that many 555 Greenwich features—tenant flexibility, advanced air filtration controls, the lobby’s anti-congestion orientation and setbacks creating 10,000 sq ft of outdoor terraces—all were designed before COVID-19 but are in high demand today as tenants seek to adjust space priorities, Cook says.

“Every part of our thinking was to design the healthiest workplace,” he says. “That was all planned pre-pandemic—and all reinforced post-pandemic.”

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment