Inflation, added scope of work and the need for additional contingency funds have added just over $2 billion to the price of an ongoing high-speed rail line project in California, according to the agency that oversees it, and questions remain over funding for future planned segments.

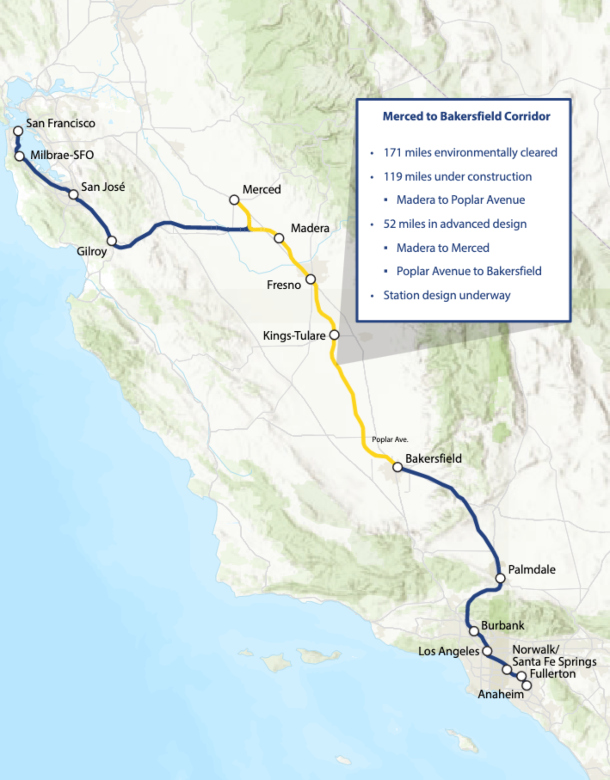

Members of the California High-Speed Rail Authority (CHSRA) board voted March 16 to increase the project expenditure authorization from $17.9 billion to $20 billion. The agency is leading ongoing work to build 119 miles of high-speed rail line in California’s Central Valley. This effort has been spread between four construction packages awarded to three contractor teams, and has ambitions for more, most immediately including plans to extend that line into a 171-mile route between Merced and Bakersfield.

Changes to the scope played a significant role in rising costs—more than 1,100 change orders have been approved as of March 6. Authority CEO Brian Kelly said during the board meeting that construction was started out of sequence to meet the terms of a $2.5-billion federal grant, which required that funds be expended by September 2017. That deadline was met, but design was only 15% completed and only limited right-of-way had been acquired at the time construction began in 2015, according to the agency.

“Everything we do requires a change order,” Kelly said.

To avoid those issues, future sections would go to advanced design before construction begins, a CHSRA spokesperson says. The lessons learned from the first sections have been institutionalized in its staged project delivery process.

Inflation impacted the costs of all of the construction packages, according to authority CFO Brian Annis and Deputy COO Daniel Horgan. The new expenditure authorization also includes more contingency funding for each of the construction packages.

Work is underway on 119 miles of the planned 171-mile Merced-Bakersfield segment. Map courtesy of California High-Speed Rail Authority

Work is underway on 119 miles of the planned 171-mile Merced-Bakersfield segment. Map courtesy of California High-Speed Rail Authority

The increased authorization adds $453 million for additional costs and $392 million for contingency for Construction Package 1. That work is led by joint venture Tutor-Perini/Zachry/Parsons. The contract covers work along 32 miles between Madera and Fresno counties, including a tunnel, two viaducts and the realignment of State Route 99.

Construction Package 2-3 covers 65 miles from the end of the first package in Fresno to 1 mile north of the Tulare-Kern county line with about 36 grade separations, including viaducts, underpasses and overpasses, according to CHSRA. Dragados/Flatiron is the joint venture contractor. The new authorization adds $687 million for additional costs and $643 million for contingency.

Construction Package 4 is led by California Rail Builders, a joint venture of Ferrovial-Agroman West LLC and Griffith Co. The contract covers 22 miles going south from the end of the prior package. The added expenditures include $27 million for additional costs and $51 million for contingency. Authority officials anticipate completion of this segment this summer.

The project has supported 10,000 construction jobs so far, according to the agency.

Costs and Funding

The authority also recently released its annual project update report, which includes projected costs and potential funding sources. The updated capital cost estimate now includes double-track and full build-out of stations and other facilities, while previous estimates represented just single-track phased implementation for Merced-Bakersfield. The agency raised its estimate for the 171-mile route connecting Merced to Bakersfield, including the Central Valley segment, from $25.7 billion to as much as $35.3 billion.

Meanwhile, forecasted funding through 2030 ranges between $23.5 billion and $25.2 billion, leaving a potential gap. The California HIgh-Speed Rail Peer Review Group, an independent state-appointed panel established to assess the feasibility of authority plans, has repeatedly questioned funding for the project. Louis Thompson, group chair, says the funding problem has only gotten worse as work progressed.

“It isn’t stable,” he says. “In our opinion, it’s not possible to manage a project of this size with that kind of funding. You would never try to do something like this without knowing you have enough money.”

The authority is targeting $8 billion in grants from federal programs funded by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act to help pay for segments between Merced and Bakersfield. A spokesperson says the authority hopes to achieve a state-federal cost balance that is closer to parity, as opposed to the current 85% state, 15% federal share.

“This uncertainty of funding and costs presents challenges, but this is not new, as the authority has never had permanent or stable funding at either state or federal level,” CSHRA wrote in the project update report. “Significant progress has been made despite this challenge. To meet the challenge going forward, the authority will aggressively pursue new federal grants from [IIJA] and beyond. We have also developed a phased approach to keep the project advancing in increments as funding is secured.”

The authority aims to eventually extend the line 500 miles between San Francisco and Anaheim as part of Phase 1. It has received environmental approval for 422 miles of the proposed route so far, and says it will seek certification for a Palmdale-Burbank segment this year that would raise the approved section to 465 miles. However, those future plans face further funding questions.

Proposed work connecting north to Gilroy, San Jose and San Francisco is expected to cost $35.5 billion, and work extending south from Bakersfield through Palmdale, Burbank, Los Angeles and Anaheim is projected at $52.8 billion. Combined with additional program-wide costs, the authority projects a capital cost, with inflation, as high as $127.9 billion for the Phase 1 program from San Francisco to Anaheim, meaning more than $100 billion in needed funding remains to be accounted for if those plans advance.

“This is going to pose a very serious question to the legislature,” Thompson says. “How would they pay for it? And what are the state’s priorities for this money as opposed to other projects?”

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment