Natural Disasters

Decade After Superstorm Sandy, NYC Region Still Builds Up Resilience

Resilience projects in various stages of design and construction around New York City are intended to improve resilience to coastal storms and rising sea level.

Rendering courtesy of NYC Lower Manhattan Coastal Resiliency

A decade after Superstorm Sandy exposed New York City and its bistate region to the high risks of extreme weather tied to climate change, billions of dollars have moved to projects to improve resilience against coastal storms and rising sea level. But today, those threats still largely remain with public projects to mitigate them still in varying stages of planning or construction, government officials say.

The storm, which struck the region on Oct. 29, 2012, measured 1,000 miles wide and killed 44 people. More than 100 homes in the city's Breezy Point, Queens section burned down, while some subway tunnels filled with water, and damage to critical infrastructure temporarily limited millions of residents’ access to essentials such as drinking water, wastewater treatment, power and health care across the region.

Officials estimate the total cost in damage and lost economic activity in the city alone was $19 billion.

Fast Forward: New York City's Resilience Infrastructure

Ten years later, the collective market rate value of New York City real estate in the 100-year floodplain has increased 44% since Sandy to more than $176 billion, according to a recent report from the New York City Comptroller. More than three-quarters of land designated for transportation and utility infrastructure also sits in the floodplain.

By 2050, the comptroller’s office projects 26% of city public housing developments will be there, along with real estate accounting for $3.1 billion in annual tax revenue.

“Sandy wasn’t just a storm; it was a warning,” Mayor Eric Adams said in a statement. “Another storm could hit our city at any time and that is why our administration is doing everything we can to prepare and protect New Yorkers.”

As of June, the city had spent about $11 billion, or 73%, of the $15 billion in federal funding it received for Sandy recovery, according to the city’s online Sandy Funding Tracker. Adams says the city will need about $8.5 billion more in such funds for a slate of planned climate adaptation projects aimed at improving resilience. Outside government agencies have also proposed solutions costing tens of billions of dollars more, including the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers with its tentative plan to build a series of coastal storm defenses throughout the New York-New Jersey harbor and its tributaries at an estimated cost of $52.6 billion.

That $8.5 billion Adams hopes to claim would allow New York City to complete a variety of resilience infrastructure projects.

On Oct. 26, city officials held a ceremonial groundbreaking for one: the Brooklyn Bridge-Montgomery Coastal Resilience project. The NYC Dept. of Design and Construction awarded a $349-million contract to Lawrence, N.Y.-based John P. Picone Inc. for the project, records show. Work will include installation of flood walls and flip-up barriers along the east side riverfront of Manhattan’s Two Bridges neighborhood.

NYC Parks also has developed a plan for East Harlem that recommends creating a stormwater management network of both green and gray infrastructure, raising the waterfront and integrating it with drainage improvements, while the NYC Economic Development Corp. has proposed a Financial District and Seaport Climate Resilience Master Plan that calls for raising the waterfront and extending parts of it into the East River. The Manhattan Greenway project, which would eventually link a 32-mile pedestrian and bicyclist path around Manhattan, is also accounting for sea level rise. As ENR previously reported, portions of the Greenway being built along the East River are high enough to accommodate 3 ft of sea level rise.

City officials are also developing resilience plans for Coney Island Creek in Brooklyn and Tibbetts Brook in the Bronx, which the mayor’s office also identified as potential projects for federal pre-disaster mitigation grants.

To expedie projects, Adams said he would work with state lawmakers to pass legislation to allow the city to use progressive design-build for project delivery. A spokesperson for Adams said the change would promote early collaboration and identify potential engineering and construction challenges, as well as solutions, before agreeing on a final price.

Carlo Scissura, president and CEO of the New York Building Congress, praised Adams’ efforts to fortify city infrastructure against future storms, saying in a statement that the mayor is “wisely putting forward crucial project and policy proposals" to protect the city.

Gateway Tunnel

The proposed $16.1-billion Gateway Hudson River rail tunnel project would also improve resilience, its designers say. After construction of a new tunnel linking New Jersey to Manhattan, plans call for rehabilitation of the existing tunnel, which was damaged by Sandy. The full upgrade will take a year for each of the two tubes, according to the U.S. Dept. of Transportation’s Federal Railroad Administration.

The Long Island Rail Road is planning a flood protection project at its West Side Yard in Manhattan, which also encompasses the portal and vent shaft for one end of the existing tunnel. This was the location where floodwater entered the tunnel during Sandy, according to a report from the Federal Railroad Administration, NJ Transit and Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. The plan calls for construction of a new wall, deployable flood barriers and drainage improvements.

Amtrak also plans to install flood barriers around a ventilation shaft on the New Jersey side. Floodwater did not reach the shaft during Sandy, but officials say the probability of the area flooding will rise through the 2030s.

New York Harbor Project

The Corps of Engineers' New York District has developed a tentative plan that may be the largest and most significant to protect the region against coastal storms.

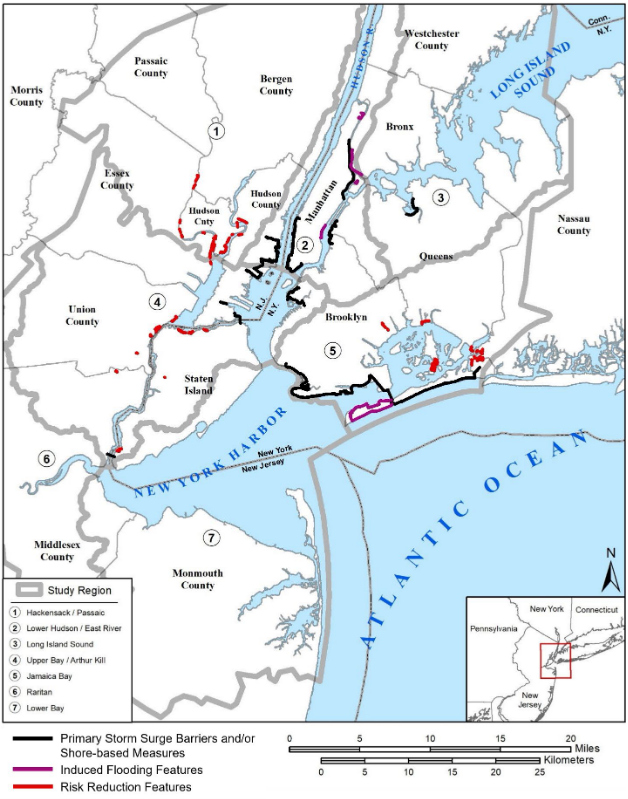

The proposal, which officials released for public comment in September, calls for construction of a series of breakwaters, seawalls, levees, floodwalls and other shore-based measures at targeted points around the New York Harbor from Staten Island to Jersey City in the west, and from Manhattan to Queens in the east, along with protections along tributaries across the city and in parts of northeast New Jersey.

The Corps will accept public comment on its tentative plan until Jan. 6, 2023

The Corps will accept public comment on its tentative plan until Jan. 6, 2023 Map: Courtesy of US Army Corps of Engineers

The plan is scaled down from an earlier considered option that called for construction of a 6-mile seawall between Queens and Sandy Hook, N.J. at a cost of $119 billion. But the Corps says its tentative selection would actually offer the greatest economic benefits of the options—some $3.98 billion annualized over 50 years.

A final report on the proposal is due to be released in 2024, and then the project would go to Congress for funding approval.

While developing that plan, the Corps district has also been working on more localized projects to protect coastal areas in the city, Long Island and New Jersey. Six projects authorized by Congress via a $6-billion supplemental spending bill shortly after Sandy are currently in progress, according to the Corps.

In Rockaway, Queens, the Corps is working on a $702-million coastal storm risk reduction project that includes building a reinforced steel sheet pile dune, plus building and extending groins and restoring the beach. Construction on nature-based storm surge protection features on the Jamaica Bay shoreline is set to start in 2025.

Regional Approaches

On Long Island, the Corps has completed shoreline reinforcement projects at Montauk and from Fire Island to Moriches Inlet. More are in the works. Construction of a $44-million stone revetment at Montauk Point Lighthouse is underway and expected to complete in 2023.

The Corps recently announced award of a $24.5-million contract to Houston-based Great Lakes Dredge and Dock Co. LLC for dredging along 83 miles of Suffolk County coastline—the second contract in a $1.7-billion project to manage coastal storm risks from Fire Island to Montauk Point. The project will also include renourishing beaches, removing existing groins at Ocean Beach and Fire Island and elevating about 4,400 structures in the 10-year floodplain.

In New Jersey, the Corps awarded a $50-million contract this year to Cranford-based Weeks Marine Inc. for the first phase of a $382-million Union Beach coastal storm risk reduction project. The contractor will construct a beach berm with planted dunes and terminal groins along Raritan Bay in Monmouth County. Future phases will also include construction of levees, floodwalls, pump stations and tide gates.

“This particular area of the shore region has long been susceptible to nuisance flooding and major storm events, which is why we must undertake these kinds of improvements to protect lives and property as well as improve quality of life for residents,” said Shawn LaTourette, commissioner of the New Jersey Dept. of Environmental Protection, in a statement.

Ongoing Corps projects in New Jersey also include work at a former industrial area along the Passaic River in Newark, where a bulkhead has been built and riverbank restored. Future project phases will involve building a waterfront walkway and park. In Port Monmouth, the Corps is building a series of levees, floodwalls and other protections. Two more contracts for the work are planned for award in 2023.

Despite several hurricanes and other storms, the region has not been hit as hard since Sandy, but others have threatened. In 2021, the remnants of Hurricane Idea, then a post-tropical cyclone, set a city record for single-hour rainfall, causing flooding, 13 deaths and property damage officials have estimated at hundreds of millions of dollars. Adams said preventing further damage and deaths will continue to require quick action—and funding.

“New York City’s infrastructure projects are more complex, novel and unparalleled compared to any other American city, but many remain in various stages of completion, and we need our partners in the federal government to help provide us with regular and reliable resiliency funding,” he said.