Paul J. King Jr. has been the catalyst for positive change in Chicago construction and on jobsites nationwide.

King’s résumé makes the case. As the executive director of the United Builders Association of Chicago, he helped organize the National Association of Minority Contractors. He also founded UBM Construction, which became the largest black-owned contractor in Illinois.

King also founded O’Hare Development Group, one of the first minority-owned developers in the state, and even became a consultant to the U.S. Dept. of Labor in its efforts to craft minority contractor and labor participation rules on federally funded construction contracts.

Yet before all of that, it was organizing and standing up to a closed system that kept Black Americans out of building trade unions and the federally funded projects in their Chicago neighborhoods that first put ENR Midwest’s Legacy Award recipient at odds with business-as-usual.

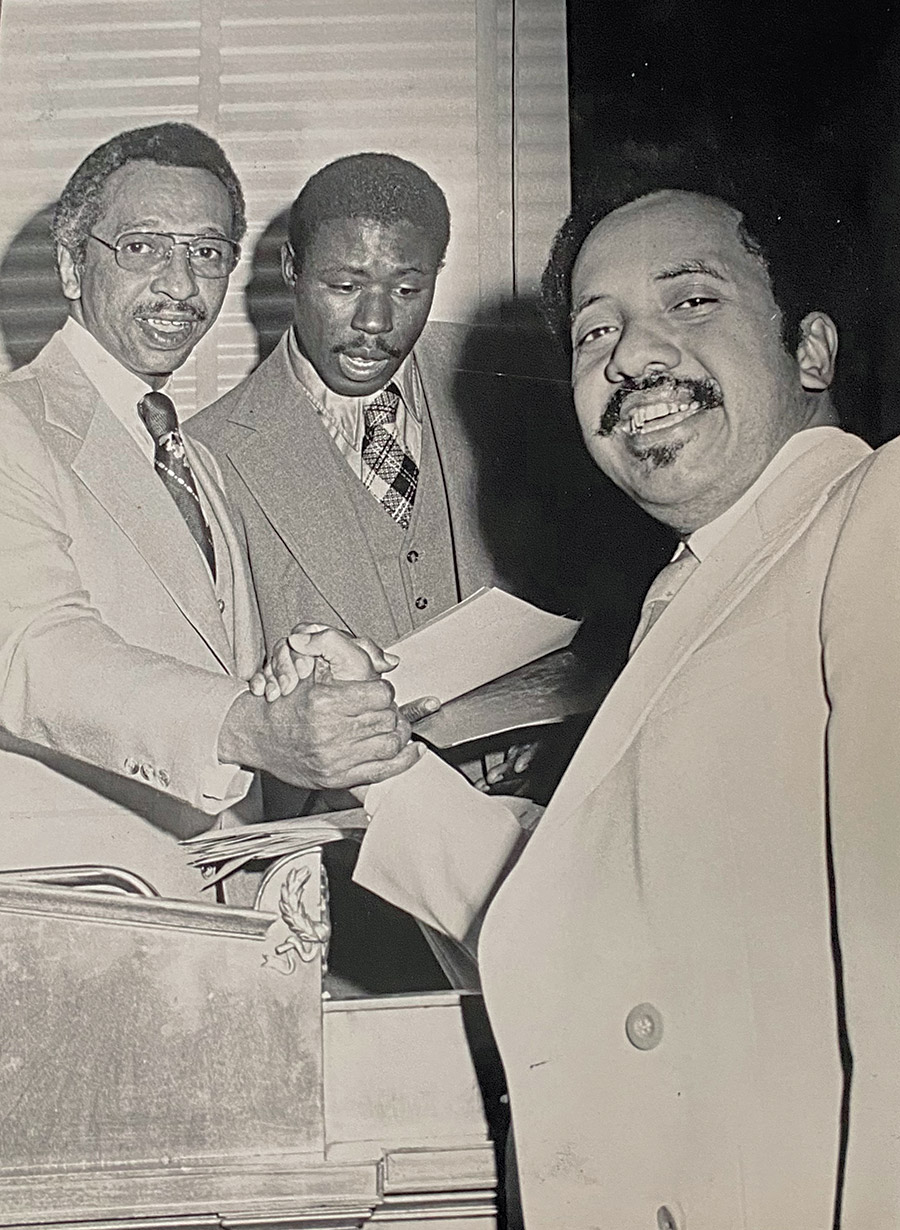

Paul King with the late Parren Mitchell and one of his congressional aides when the businessman and legislator were drafting the federal contract language that would become known as affirmative action.

Photo courtesy of Paul King Jr.

Fighting for Representation

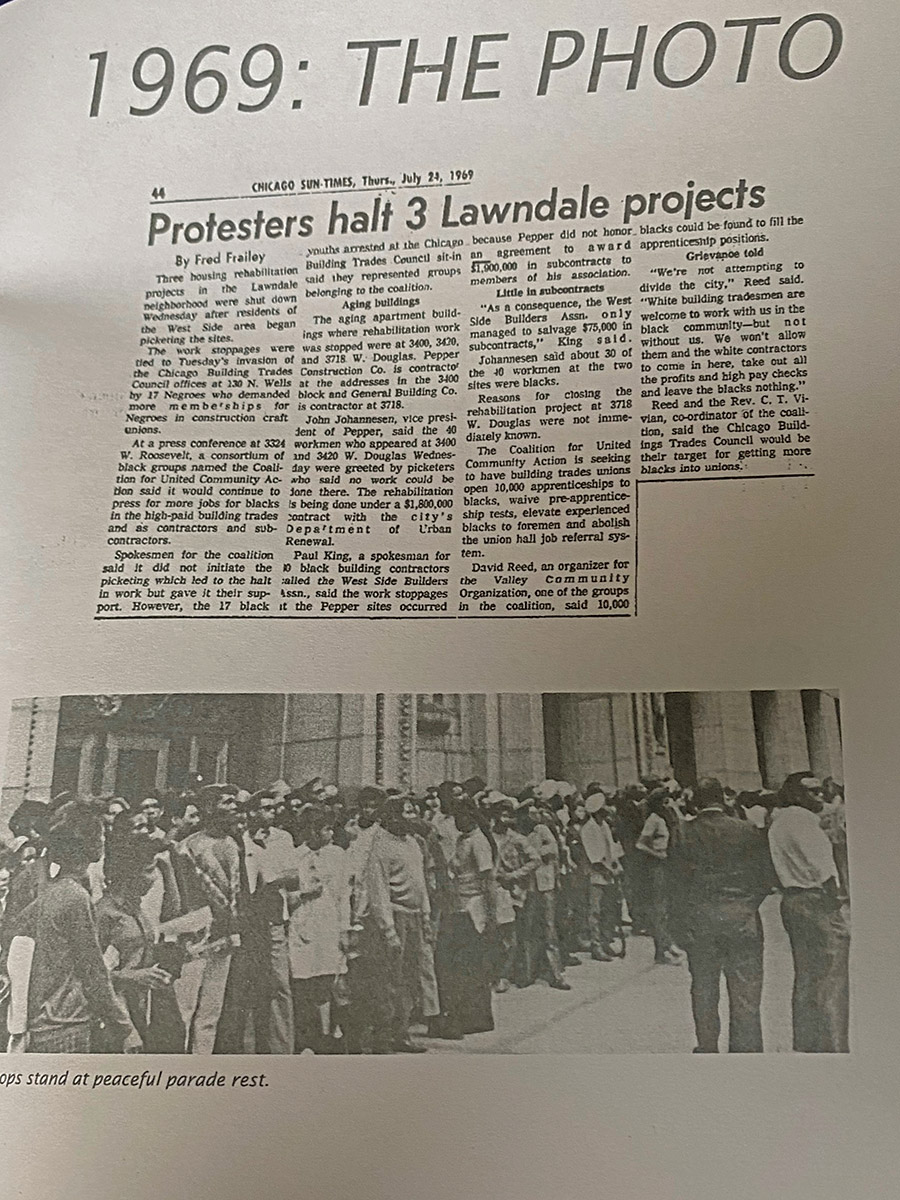

In 1969, King led a group of 80 black contractors known as the West Side Builders Association in a peaceful protest that shut down a federally funded construction project on West Douglas Boulevard. It was the first of more than $80 million in closed projects the group opposed, forcing local trade unions and the Associated General Contractors to the negotiating table to discuss how to open the trades and contracting industry to Blacks. At the time, the unions were 97% white. Negotiating for the unions and contractors at the time was Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley.

“We wanted our fair share of jobs, our piece of the pie. Blacks would pass construction projects in the neighborhood and see nothing but white workers. It was a slap in the face and a daily insult.”

—Paul King Jr., Founder and CEO, UBM Inc.

“We wanted our fair share of jobs, our piece of the pie,” King says. “Blacks would pass construction projects in their neighborhoods and see nothing but white workers. It was a slap in the face and a daily insult.”

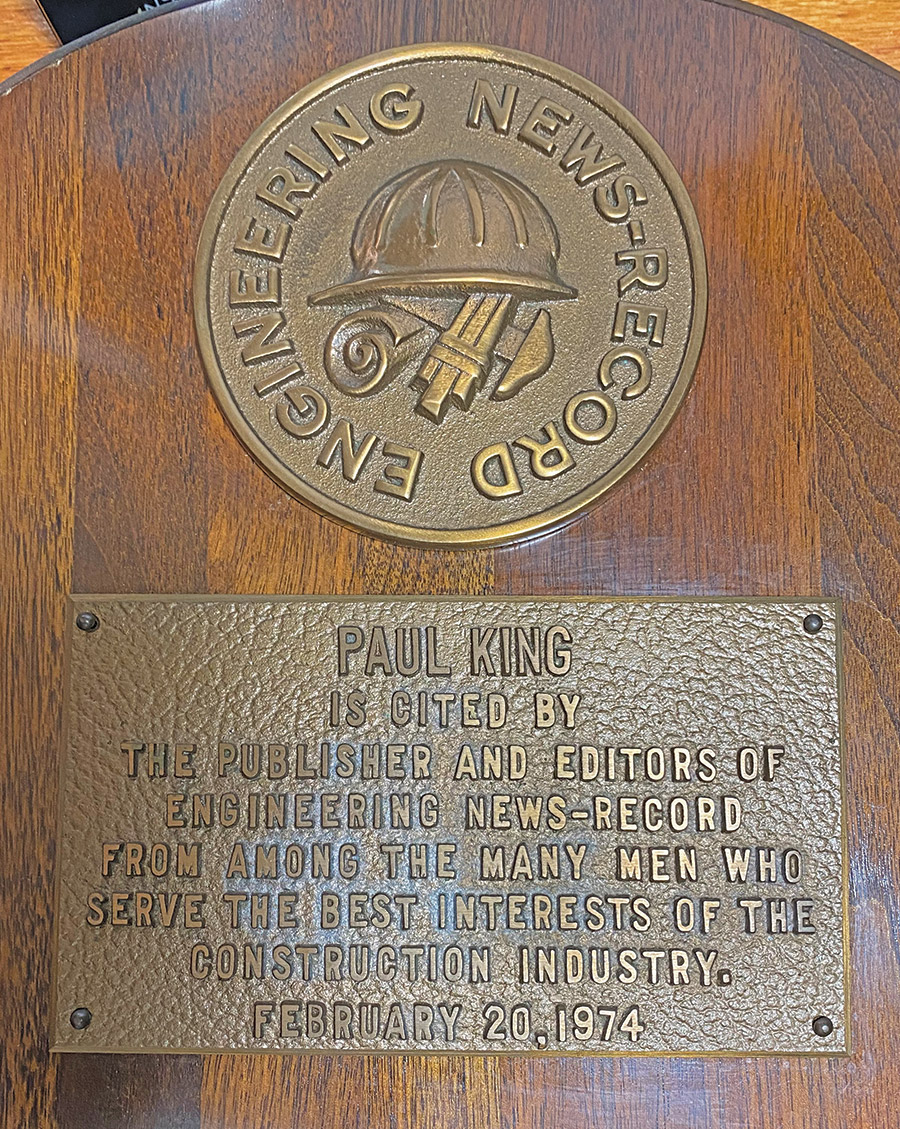

It would be a career-long fight for King to create opportunities for Black-owned businesses in construction as a leader in both Chicago and Washington, D.C. Whether it was through the Labor Dept., the Small Business Administration or the work of NAMC, King pushed for more access to bonding, loans and the lucrative public projects that can turn small contractors into larger ones. He was named an ENR Newsmaker in 1974 for his efforts.

King was always interested in the business side of construction even before founding UBM in 1975. His father, Paul King Sr., was a successful wholesale produce distributor dating back to the Depression and the first man to bring fresh, Southern produce to Chicago’s supermarkets. King’s uncle taught him to paint—a skill that became the foundation of his future construction career.

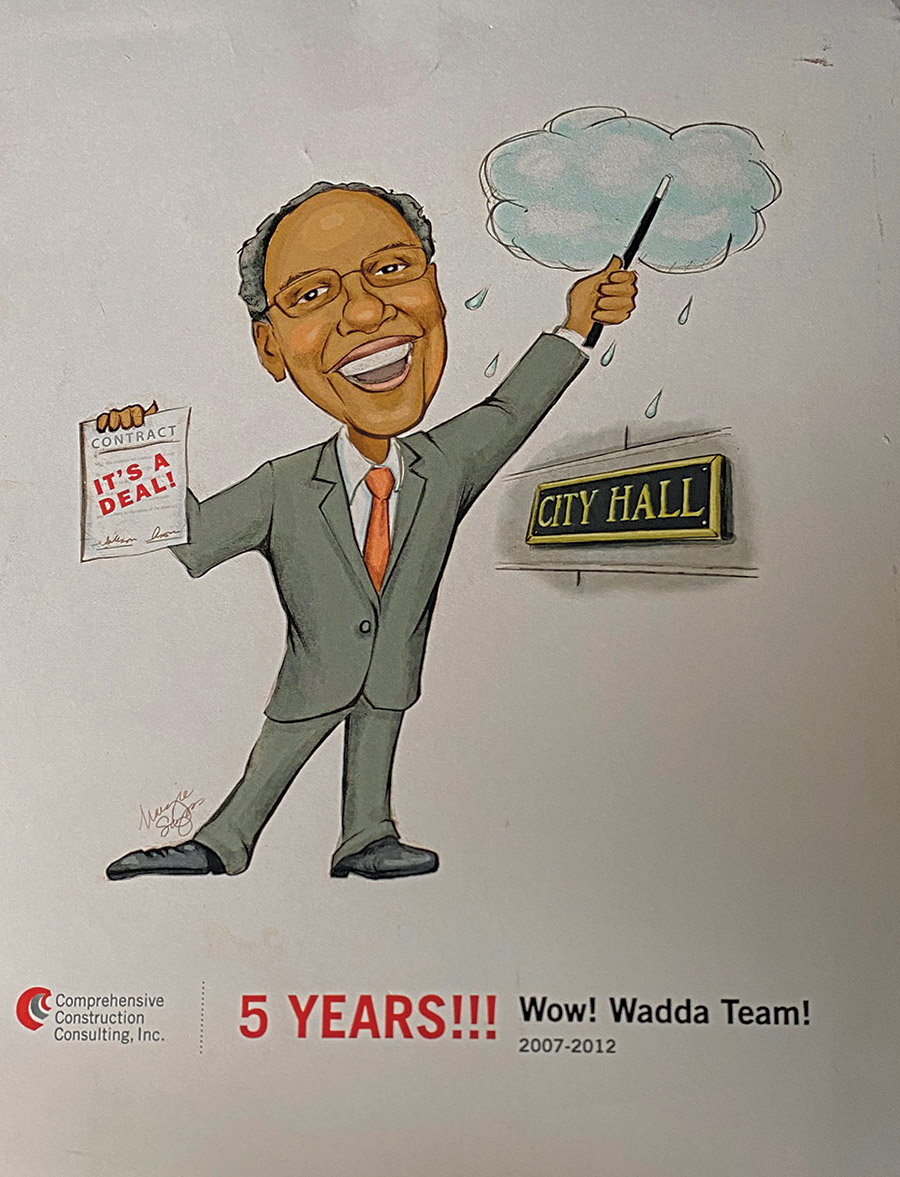

Paul King celebrates five years of business development at Comprehensive Construction Consulting in this illustration.

Photo courtesy of Paul King Jr.

Actions of Affirmation

In his 2009 memoir, “Reflections on Affirmative Action in Construction,” King recalled 40 years of the program meant to set aside percentages of federal contracts for minority-owned firms. As an adviser to U.S. Rep. Parren Mitchell—the first black congressman from Maryland and a founder of the Congressional Black Caucus—King was instrumental in the legislator’s addition of an amendment to a 1976 public-works program that required state and local governments applying for federal contracts to reserve 10% of funds for minority-owned businesses.

“He and Parren Mitchell got together and wrote a lot of the federal affirmative action bills that were actually implemented,” says John Bolden, an engineering principal at Comprehensive Construction Consulting and King’s business partner. “It more or less provided opportunities, not just only for general contractors in the Chicago area, but it affected general contractors in the construction industry nationwide.”

In 1969, Paul King and the West Side Builders Association stood up against trade unions and the contractors for which they worked for excluding black workers and eventually shut down 80 worksites.

Photo courtesy of Paul King Jr.

That contract language became standard for federally funded projects. “One out of every seven jobs is in some way related to construction. It’s a big, big business,” King says. “In trying to advance the Black contractor, we’re talking about trying to stimulate an agent for the cause of Black economic development. It’s not just trying to make an individual rich; it is a process toward Black economic empowerment.”

King participated in a Chicago Tribune series of investigative articles that highlighted supposed minority subcontractors hired onto large projects such as the McCormick Place expansion that were only minority on paper, without a Black face on the site.

“Those fronts and those fraudulent people that are doing that kind of thing, every one of them is taking business away from the growth and development of Black firms,” King says. “Jesse Jackson Sr.’s brother Noah Robinson was famous for doing that.”

Robinson, Jackson’s half-brother, operated several Chicago companies that capitalized on programs to aid minority businesses, but often hired white-owned firms to do the work. He was eventually convicted of unrelated racketeering, narcotics and murder-for-hire charges.

King also says that watching policies and contract language deviate from requiring minority representation to requiring minority or women-owned firms has led to more abuse of the process that goes against the spirit of the law’s original intent. He notes that contractors that simply list a wife or other female relative in a top leadership role, when the firm is actually controlled by men, suppress Black and minority entrepreneurship.

“Now, it’s everybody and their mother and a lot of folks who never even saw a protest march that are benefiting from affirmative action legislation,” Bolden says.

Photo courtesy of Paul King Jr.

Educating the Next Generation

A thread that runs throughout King’s activism—and is evident in his writings in ENR Viewpoints as well as in the magazines Black Scholar, Black Enterprise and N’Digo—is that education is what truly creates opportunity.

“You can’t have construction productivity or safety without reading, so we find ourselves in a situation where all the Black boys that would be interested in our field are in jail,” King says. Programs for teaching incarcerated young men the construction trades so they can be both safe and productive when they get out are as important now as when he started fighting for jobsite inclusion, King says.

“We don’t have enough Black young men that are aware of the opportunities in construction. There has to be a major educational effort as well as a recruitment effort.”

—Paul King Jr., Founder and CEO, UBM Inc.

His youngest son, Timothy King, has taken his father’s teachings to heart by opening Urban Prep Academy, a network of public charter schools in Chicago. Its three schools in the Bronzeville, Englewood and Near West Side communities serve more than 1,500 young men—the first such all-male charter schools in the U.S.

Paul King says more must be done in construction to attract young Black men. “We don’t have enough Black young men that are aware of the opportunities in construction,” Paul King says. “There has to be a major educational effort as well as a recruitment effort.”

He also realizes that the lack of labor that contractors face today is a problem that was created by exclusionary policies decades ago.

Still active in the business, Paul King is today the primary business developer and rainmaker at Comprehensive Construction Consulting Inc., where he gives credit to his partners, Bolden, President and CEO Lynn Dixon and principal Doug Conover.

“I love my partners, they allowed me to get out there and showboat,” he says.

He has lectured at Roosevelt University in Chicago and is working on a second book, due out later this year. He and his wife, LoAnn, still live in the city.

Writing in the foreword to “Reflections on Affirmative Action in Construction,” Gwendolyn Keita Robinson, executive director of Chicago’s DuSable Museum of African-American History, said, “There are not many people who get to see their ideas come to fruition or their lifetime struggles rewarded. Paul King is one of those people, although he would be the first to say ‘a luta continua’—the struggle continues.”