Nestled into the north shore of Lake Superior, the city of Duluth, Minn., sits at the westernmost point of the Great Lakes. Formed by the glaciers that created the lakes themselves, much of Duluth’s Central Hillside neighborhood is built into a rocky, iron-rich slope with soil no deeper than 20 ft to 30 ft at any point and much of it is exposed rock.

The tallest building in Duluth today is only 16 stories and 247 ft tall due to the difficult ground and the winds blowing in off the lake.

Despite the challenge that Essentia Health’s existing St. Mary’s Medical Center and two clinics posed in Central Hillside, the owner chose to build 942,000 sq ft of new space on top of the existing hospital and where the clinics had been. The existing buildings have three different street elevations jutting into the hillside. The $900-million hospital expansion is on track to be completed in 2023, and the master plan for the Vision Northland medical campus consolidates much of Essentia’s downtown campus while replacing the existing St. Mary’s Medical Center.

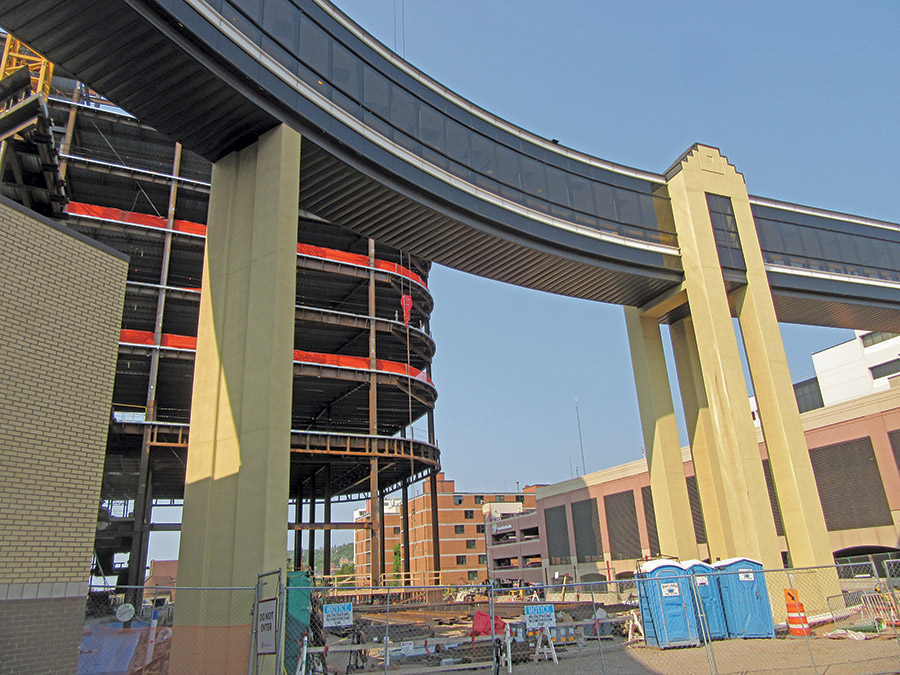

The design for Essentia Health’s new consolidated campus combines an inpatient tower with clinics and outpatient services as well as a children’s hospital further down the hill to Superior Street. A circulation spine runs near the outside of all of the buildings.

Rendering courtesy of Ewingcole

“From an organization standpoint, we’re really looking to consolidate our campus into a smaller footprint by building more vertically so we are able to tie into two of our existing clinics,” says Dan Cebelinski, Essentia Health’s director of facilities.

In 2017, architect EwingCole took on the challenges that include the rocky hillside, the need to build on top of a working hospital that had to stay open during the construction phase and connecting it to the clinics. The interconnected new inpatient hospital and outpatient building will rise 19 stories and 344 ft over the combined building’s Superior Street elevation. Between the two towers, eight steel trusses form a link between the lower outpatient building along Superior Street and the hospital’s bed tower along Second Street. More outpatient space, hospital support space and a new emergency room fill the gap between them including spanning over First Street. Two sizes of trusses are being used: one 69 ft long and weighing 42 tons and one 74 ft long and weighing 48 tons.

Crews had to deal with the steepness of the Central Hillside neighborhood for deliveries and laydown space. The tight site was bounded on three sides by hotels and parking garages.

Photo by Jeff Yoders/ENR

Several of the floor heights in the connector building that spans first street had skywalks to existing buildings that made floor heights inconsistent.

Photo courtesy of McGough Construction and Jeff Yoders/ENR

“One of the goals was to improve efficiencies,” says Robert McConnell, president of EwingCole. “We addressed the challenge presented by all of these different buildings crossing streets and skybridges early in the planning stages, leading us to as efficient a building design as possible. The site ends up being advantageous because of the split that a vertical orientation can give you—that separation between inpatient and outpatient spaces.”

When general contractor McGough Construction started construction in 2019, the first thing crews had to do was remove existing structure and blast more than 40,000 cu yds of rock from the hillside. Vibration from blasting and excavating had to be monitored to preserve the walls and foundations of the existing buildings that were being incorporated into the new project, but also to allow medical care to continue at the existing St. Mary’s hospital. The emergency room had to remain open 24 hours as well.

“Each of the floors are all a different floor-tofloor height because they were tying in one of those buildings at a different height.”

—Robert McConnell, President, EwingCole

“When we started in December of 2019, we had five to six months of continuous blasting,” says Phil Johnson, project manager for McGough on Vision Northland. “The reason it took so long is that we had to restrict the size of the vibration. It was very much surgical; the blast times were scheduled at 12:30 p.m. and 4:30 p.m. every single day. All of the surgeons, operating room staff, health care staff and patients would know it was happening, horns would go off and signal it.”

McGough also had to place a 6,000-cu-yd concrete counterfort wall, 260 ft long and 59 ft high along Second Street to anchor the new hospital tower.

Because of all of the connections to the existing buildings, the floor heights in the lower building and the lower tower and the connector space over First Street weren’t consistent. The circulation spine that EwingCole designed extends the length of the building along the glass exterior of the hospital and outpatient building and the middle building over First Street, so family and discharged patients can walk through the building without interacting with staff and patients in the interior.

“Each of the floors are all a different floor-to-floor height because they were tying in one of those buildings at a different height,” McConnell says. “So, it’s 16 ft on one floor, the next one is 26 ft. Next one will be 18 ft. Once we got to the tower, it was very regular, 14 ft up every floor, but because of the elevation changes, that wasn’t the case for the lower floors.”

The new hospital is situated on the shore of Lake Superior, making the flight path from Duluth Airport as well as the flight paths of migratory birds critical design considerations.

Photo courtesy of McGough Construction and Jeff Yoders/ENR

When the project started, McGough was able to purchase all 12,300 tons of structural steel, including the trusses spanning First Street, that were necessary for the project before the pandemic set in motion a series of pricing and lead time increases.

“We’ve been tracking material risks throughout the project, and one of the early risks we were concerned about was being able to get glass and aluminum on time. That hasn’t been a problem,” says Jeff Dzurik, project executive at McGough. “However, obscure things like mineral wool insulation have. Right now [in late July] there’s about a six- to eight-month lead time on mineral wool installation.”

Unitized glass assemblies arrive from Viracon facilities in Canada ready to be installed.

Photo courtesy of McGough Construction and Jeff Yoders/ENR

Dzurik explained that the binder in mineral wool became difficult to obtain for suppliers because production facilities in Texas were shut down due to freezing conditions there in February 2021 and suppliers simply haven’t caught up yet.

“There was also a big fire out in New Jersey that took out a million square feet of warehouse,” he says. “Ironically, a warehouse burned down that stores mineral wool insulation, which is supposed to be fire resistant, but the warehouse wasn’t.”

The building height was a challenge as it had to be designed around a flight path to and from the Duluth Airport and the glass of its facade had to be visible to smaller fliers as Duluth is in a migratory flight pattern for several species of birds.

There are 224,489 sq ft of glass curtain wall specified for the Vision Northland campus.

Photo courtesy of McGough Construction and Jeff Yoders/ENR

“Some of the programs that didn’t need a lot of daylight, we actually embedded them in the rock of the foundation. Things like radiology departments and the lab spaces are in cuts in the grade,” says Saul Jabbawy, regional director of design and a principal in EwingCole’s Philadelphia office. “Their existing buildings were at three different connection locations. That created a bit of a challenge. You’re connecting to three different structures at different elevations in the existing buildings.”

“We had five to six months of continuous blasting. The reason it took so long is that we had to restrict the size of the vibration. It was very much surgical.”

—Phil Johnson, Project Manager for McGough on Vision Northland

Like many projects over the last two years, Vision Northland has had to deal with work restrictions related to the COVID-19 pandemic. While Minnesota never shut down construction and the project continued as essential infrastructure, McGough had to take measures such as building a new skyway only for construction workers through the existing hospital to keep patients and personnel properly distanced from project workers during the height of the pandemic. There was only one COVID-19 patient in the existing hospital during ENR’s July visit.

“We’ve been really fortunate that we have not had any significant impacts from COVID,” says Stephen Catts, senior program director on the Vision Northland project for owner’s representative Hill International. “We’ve been remarkably fortunate whether that’s supply chain or with our workforce.”

In addition to the tight site, McGough Construction had to maintain skyways and connectors to the existing hospital, local parking garages and hotels through the site.

Photos by Jeff Yoders/ENR

The pandemic has, however, forced Essentia Health and hospital systems across the country to rethink their plans.

In light of many concerns related to pandemic health care, in October 2020 Essentia leadership asked the project team to study what would be required to modify the design to have all beds in the building be ICU compatible or acuity adaptable from regular patient care rooms to full ICU rooms. Executing this change would result in 288 beds that could flex to full ICU levels of care. The project currently has 64 ICU beds and 96 acuity adaptable beds.

“We need to build in flexibility in these floors,” says Dr. Jon Pryor, president of Essentia Health’s east market. “We have joined with other health care systems to request from Congress $10 billion across the US and $100 million for us [Essentia Health] to convert a lot of our med/surgical rooms into ICU-compatible rooms.”

Essentia presented its plan to members of Congress for federal funding not only for its own proposed changes, but also to create a strategic framework across the U.S. for handling future pandemics. Its proposal, the National ICU Pandemic Readiness Fund, seeks to equip 2,500 code-compliant ICU beds across the country. The readiness fund has not been included in pandemic relief legislation by Congress yet, but Essentia is positioning itself to move forward with the bed changes for the Vision Northland campus.

Local migratory birds are one group that usually doesn’t get a say in a hospital’s design, but as Duluth’s citizens care a great deal about time spent outdoors and make a point of enjoying nature, it was deemed essential that the design of the building should protect those birds that fly south directly through the site of the tall building.

The skin of the whole building was designed to have a visible frit pattern that birds can see far away that lets them know a glass building is near. The frit pattern becomes busier on the specialty glass the higher up the building you look, where most migratory birds fly.

“It’s a much calmer, barely visible frit [the closer you get to the ground] because we didn’t want it to get that busy on the street level,” Jabbawy says. “At the base level we have these very large patterns of brick panels that come down the facade and, with sunshades and a series of other elements, the face of the building on Superior Street [has contrasts that are visible to birds]. The base has a much simpler frit pattern that kind of goes away but still protects the birds.”

The glass frit pattern was designed to be visible to birds from a distance as well as close up.

Photos by Jeff Yoders/ENR

Higher up, the frits form a design visible to the avian and human eye. To make that design, glass supplier Viracon takes digital image files from EwingCole and applies specific frit patterns to the glass. Review of the glass adds some additional steps to the process on the front end, Dzurik says, but once the glass is fabricated, other than placing it in the right orientation and the right location, it physically installs the same as regular glass. One complication for what’s believed to be the largest bird-friendly glass frit pattern in the U.S. was getting both the frit pattern and the low-e coating necessary for the project onto the glass.

“You want that [frit pattern] as close to the outside of the glass as possible to be the most effective for bird avoidance,” Dzurik says. “But you also don’t want to put it on the outside face of the glass because then it’s exposed to weather. So you want it to go on the interior side of that glass. But the challenge is the low-e coating usually goes on that surface of the glass, too. That’s not negotiable because that’s what reflects the UV light and holds the heat in, which is critical in this climate. Viracon is one of the only manufacturers that can put both that frit pattern and the low-e coating on the same surface.”

Viracon was able to supply all the specialty glass on time as part of its overall 224,489-sq-ft glass curtain wall order for the project. n

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment