The global push for Perkins Eastman, another New York-based architect, satisfied a need to tactically diversify in the same way the firm shifts focus to busier practice areas, says Jonathan Stark, a principal and executive director. It began “dabbling” in countries such as Brazil and Spain before establishing offices that today are in Toronto, Shanghai, Mumbai, Dubai, and Guayaquil, Ecuador.

Stark helps lead the overseas practice, but he says it needed the contributions of various partners. “It takes commitment from very senior people in the office,” he adds. “It’s grueling in terms of travel and time changes and jet lag. You have to enjoy what you’re doing.”

Langan’s Middle East foray actually follows outposts in London and Athens, which were built partly on relationships formed through large assignments, such as the Rion-Antirion Bridge, a 1 billion-Euro cable-stayed bridge spanning Greece’s Gulf of Corinth completed in 2004. Today, it is consulting on the 227-mi Elefsina- Korinthos-Patra-Pyrgos-Tsakona motorway project in Greece. Leventis says Langan also is building relationships where it handles embassy projects abroad for the U.S. Department of State.

But Leventis says registering and opening local offices is what “gives people confidence that you are for real.” Without it, he says, foreign owners and partners are likely to only tap a New York firm for “high-level advice.”

Different Strategies

The recipes for working abroad are shaped by each market, discipline, project owner, and firm. For instance, architects spread core design work across offices globally, while contractors bulk up locally as projects start.

Kohn says his partners in New York and London trek to foreign markets several times monthly for meetings, reviews, and business development. “We do most of the design work in New York and London, but we’re starting to [do some] in the local offices as well,” he says, adding that the local outposts contribute greatly to project oversight.

At Turner, while preconstruction work usually runs out of New York, local foreign offices take the lead once projects begin, often bolstered by corporate staff who relocate on site. Latt says Turner acts as construction manager or program manager abroad, and not as a general contractor.

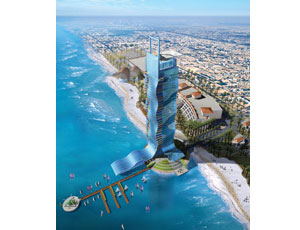

Unlike prior rounds where New York firms followed U.S.-based clients overseas, many of their projects today are for foreign developers, sometimes partnering with U.S. firms. A recent example is the Related Cos., a New York-based developer, launching a joint venture in June with Gulf Capital to build mixed-use projects with town-center planning concepts. Gulf Related will start in Abu Dhabi and Saudi Arabia.

Larger projects often spell opportunity for multiple U.S. players. Kohn says his firm has worked with numerous New York-area engineers abroad, sometimes on its own recommendations, including Leslie E. Robertson Associates, Thornton Tomasetti, Flack + Kurtz, Syska Hennessey, and JB&B, among others.

Thornton has built a significant international presence, and today is providing structural engineering services on what will be the tallest towers in three countries – Russia’s Federation Tower, South Korea’s 151 Incheon, and China’s Shanghai Tower, says James Kent, director of marketing for the firm. It has offices in Hong Kong, Shanghai, Moscow, Dubai, Abu Dhabi, and London.

Contractors also find themselves working alongside U.S. architects and engineers. Turner has Leslie Robertson as structural engineer on the Vietnam tower, and worked with Thornton on Taipei 101. But it also works with local market firms, as it is on the 70-story Mercury City Tower in Moscow set to finish next year.

New York-area contractors are less visible overseas than other disciplines, though one, Morganti Group of Danbury, Conn., has almost as many international offices as U.S. locations, with addresses in Milan, Athens, Cairo, Abu Dhabi, Dubai, and Amman, Jordan.

More than a decade ago, Tishman Construction handled construction manager assignments in London and Tokyo, as well as owner’s representative work in Brazil and development-construction projects in Poland – often working for existing clients, such as building Morgan Stanley’s European headquarters at London’s Canary Wharf. But it, too, sees opportunity abroad, and opened offices in Abu Dhabi and Dubai this year.

New York subcontractors rarely go abroad despite growing interest, Latt adds. The economics seldom work, except for those that don’t have to travel far, don’t need to move expensive equipment, or know how to marshal local labor forces, he says.

Cultural Considerations

All of the disciplines face challenges adjusting to new practices. Leventis says finding capable subcontractors and subconsultants, as well as laboratories and liaisons to local regulators, is always difficult. So is dealing with time differences between colleagues or with clients. China is a 12-hour difference on the clock, and the Middle East is up to nine hours ahead. “When you wake up, they are in late afternoon,” Leventis says. “I start doing e-mails at 5 a.m., answering e-mails that started arriving at midnight.”

Firms must also account for each country’s customs. In parts of the Middle East, for instance, the “weekend” is Thursday and Friday, leaving three common working days. Leventis says his team compromised on Friday and Saturday for Abu Dhabi, but must work around the issue in Saudi Arabia.

Some challenges require hands-on intervention. Leventis and Latt both say some foreign contractors use techniques adequate for typical projects in their markets but that are strained by needs of large, modern structures. Latt says such an issue arose on the Vietnam tower, where concrete quality was inadequate for the structure because of placement, curing, and form removal techniques. Turner teamed New York-based staff with local counterparts to develop a detailed quality control plan that resolved the issues and got the project back on schedule.

More proactively, Turner sent three top project executives last year to conduct a weeklong workshop with the Burj Dubai team, Latt says.

A key way to get oriented abroad is by partnering with local firms, as Turner has done in Mexico with contractors. “It allows us to get into a marketplace, understand the players, and to bring some strength to our services very quickly,” Latt says.

Stark says one of the most critical ingredients is finding qualified staff willing to shuttle between global offices, as well as finding local staff conversant in U.S. business, because these people underpin the business.

In that vein, Kent says Thornton has had success filling key positions by building the firm’s diversity with principals from China, Greece, and Ireland and senior executives from 16 countries.

Not surprisingly, language barriers sometimes crop up at a local project level, though most developers and design staff do business in English, Latt says.

But even when partners speak English, be careful, Kohn says, recalling a speech he gave in Poland where his remarks were translated differently than intended. “I recommend that you keep things quite simple in choice of words,” he adds. “And it’s a good idea to avoid trying to tell jokes. A sense of humor is difficult to translate. Keep things simple and direct, and let the drawings and models speak for themselves.”

Kohn says ultimately, it’s not hard to communicate good work. “There is a common language in architecture understood by most anyone who builds and develops, particularly in a commercial building,” he adds. “There’s an understanding about how these buildings need to function to be successful, and a general aesthetic about what you need to do to be successful.”

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment