Pepper Family Wildlife Center

Chicago

BEST PROJECT, CULTURAL/WORSHIP

Submitted By: Pepper Construction

KEY PLAYERS

Owner: Lincoln Park Zoo

Lead Design Firm: Goettsch Partners

General Contractor: Pepper Construction

Structural Engineer: WSP

MEP Engineer: Primera Engineers

Chicago’s Lincoln Park Zoo is the second-oldest in the nation, having opened in 1868. A Chicago landmark, the Kovler Lion House was completed in 1912 and after several renovations over the years, was no longer able to provide the type of environment that modern zoological institutions create for caring for big cats. It also was no longer the ideal venue for black-tie fundraising dinners, anniversaries or wedding receptions.

The zoo turned to architect Goettsch Partners, which designed the zoo’s Regenstein Center for African Apes, and Pepper Construction to reimagine and rebuild the old lion house. The $41-million renovation, restoration and expansion would take care to preserve the landmark, create a better experience for the lions and bring visitors closer to the action than the old moat-limited big cat habitat, which the lions had to share with tigers.

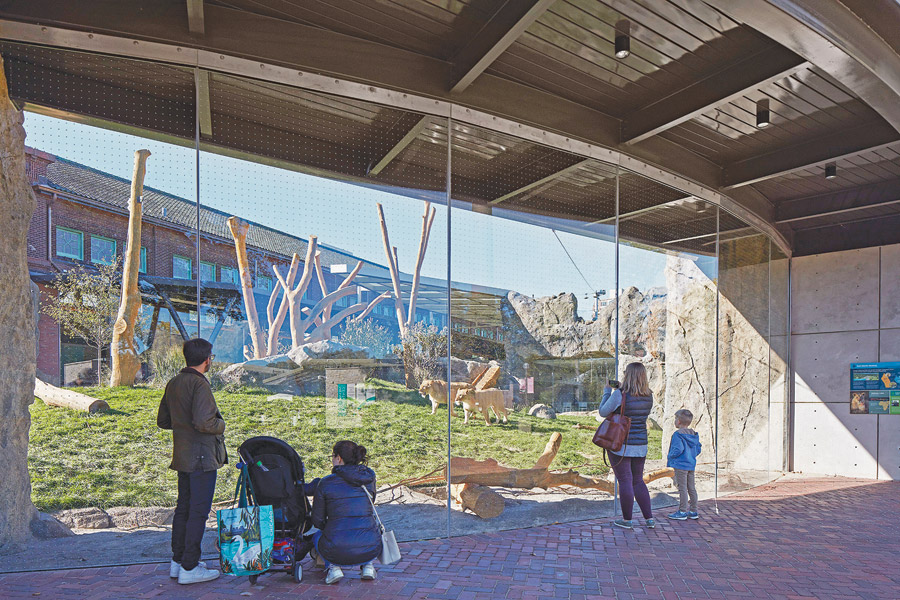

The new state-of-the-art facility gives visitors an immersive “nose-to-nose” experience with the lions.

Photo courtesy of Tom Harris

The new 54,000-sq-ft Pepper Family Wildlife Center nearly doubles the size of the previous lion habitat and provides more transparency, including a double door where, on select days, visitors can see lions get their check-ups from the zoo’s veterinarians. The immersive experience for visitors includes a recessed “lion loop” where visitors can walk under the big cats sleeping on glass skylights on the roof. Designed in collaboration with Seattle-based zoo exhibits designer PJA, the habitat focuses on providing lounging or playing opportunities for the animals and enhancing their comfort with improved heating and cooling systems as well as intricate rockwork and trees for climbing. The construction team used 3D modeling to calculate the lion’s jumps from rock to rock in the new enclosure. The lions moved to a Kansas zoo when construction began in 2019.

1.5-in.-thick wall-size panels provide an expansive view of the lions and their habitat.

Photo courtesy of Tom Harris

“It was an opportunity for us to show behind the scenes to the general public,” says Maureen Leahy, vice president of animal care and horticulture at the Lincoln Park Zoo. “There’s always this concern when people say ‘where are the animals behind the scenes?’ Bringing some more transparency shows what we mean by expert care and what all is involved in that.”

For Pepper Construction—whose second-generation owners Roxelyn and the late Richard Pepper were longtime philanthropic contributors to the zoo, having made a $15-million contribution for the project—the work meant digging up some of the North Side’s oldest underground infrastructure and finding a way to install entirely new HVAC and fiber communications systems while not disturbing zoo operations. Like most 1912 buildings, the Great Hall lacked air-conditioning and its windows required climbing a ladder to near the top of the vaulted ceiling to open or close them.

“Bringing some more transparency shows what we mean by expert care.”

— Maureen Leahy, Vice President of Animal Care, Lincoln Park Zoo

The zoo’s steam supply, which also ran through the Great Hall, had to remain operable throughout the renovation. Pepper’s crews identified and installed a new fiber route to protect the steam elements before any new construction began. The building’s steam system was cut and capped while new work took place on the Great Hall, allowing buildings on the campus that were downstream from the lion habitat to maintain operable steam heat.

“We would use different equipment to serve different areas,” says Dave Haas, project executive at Pepper Construction. “If it was a regular building, you’d be able to get away with one piece, but we had to use different equipment to serve each space to meet the human needs versus this piece of equipment’s going to meet the animal needs and this piece helps with the facilities maintenance.”

All of the MEP upgrades were concealed underground, including a new electric utility vault that was hidden in the exhibit itself, under rock. All electrical services and the switchgear room received an overhaul.

New HVAC was added to cool the Lion Great Hall, which was built in 1912.

Photo courtesy of Tom Harris and LPZ Archives

This meant excavating in and around the existing tunnels beneath the zoo and adding a new air duct along the Great Hall’s southern wall to serve as the main HVAC supply duct. The new lion habitat spans the Great Hall’s entire northern side and its design was informed by data collected by zoo personnel on lion behavior. The 1.5-in.-thick, wall-size glass panels provide expansive views of the lions in the Lincoln Park pride. The space expands the lions’ environmental options by including more climbing features such as trees and a deadfall bridge. Food ziplines simulate prey and zookeepers give the lions such items to interact with as balls and the antlers that resident antelopes shed as well as providing the lions’ favorite scents.

The Pepper Family Wildlife Center at Lincoln Park Zoo is set against the backdrop of the Chicago skyline.

Photo courtesy Pepper Construction

“What’s great about this, and the zoo really pushed us with it, was just trying to get that nose and nose contact in all of these interior spaces,” says Patrick Loughran, principal at Goettsch Partners. “In the viewing spaces in the lion loop you can really come face to face with the animals, and people are more invested in animals that they can get that close to, and that kind of closeness was previously blocked with wire mesh or a moat [in the previous habitat].”

The Lion Loop is a sunken, elliptical path that leads visitors further north into the center of the habitat past the Great Hall’s north wall. Zoo visitors can view the lions from all angles, including overhead skylights that the lions look down from. Structural steel hidden within the building allows uninterrupted, glass-only partitioned spaces on both the north wall and in the Lion Loop.

“In the viewing spaces in the lion loop, you can really come face to face with the animals.”

—Patrick Loughran, Principal, Goettsch Partners

Further north in the habitat is an 80-seat events space and meeting room at the furthest point of the loop. Two 1.5-in.-thick glass walls on the east and west sides ensure that no matter the event’s purpose, male African lion Jabari will be the biggest star of the experience just a few inches away.

While the zoo closing down during the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic gave Pepper’s crews unexpected free rein as construction work continued on essential infrastructure, the project’s overall complexity made a tall task of restoring the Great Hall’s murals and other historic pieces. The new underground zookeeper facilities also required expanding the tunnels and installing new equipment. Equipment pieces that extended from the basement out to pride rock in the center of the habitat had to be custom built and installing them was always a tight fit.

The space for African lions was designed after years of research to create an immersive habitat like their native range in Tanzania.

Photo courtesy of Pepper Construction

“We had to rough them in and get them into a location and tuck them in between the concrete and the steel that’s in that area so it was hidden still,” Haas says. None of the pieces could be short because their piping fused together at one point and descended to the underground supply system. One part of the older big cat exhibit that was adaptively reused was the moat that separated visitors from the old pride.

“We had to cut out notches into the moat wall to anchor the new foundation of the barrier fence of the new exhibit,” Haas says. “It’s also a good representation of how much more exhibit space is being provided for the animals. That was the outer wall, the exhibit that the animals didn’t have access to, and now that’s full exhibit space that’s usable land for those lions.”

The old moat would live on covered as a stormwater retention system.

“It was a perfect location for it because we really didn’t have to bring in soil to fill that void because we were building a tank,” says Greg Leofanti, vice president of Pepper. “The tank took up the void where we would’ve had to haul in soil from another site. It’s a win-win really to find a location to manage storm water and create a larger space for the lions.”

The rockwork increases horizontal and vertical space and offers the lions a high perspective.

Photo courtesy of Pepper Construction

The Pepper Wildlife Center opened Oct. 14, 2021, with Roxy Pepper and her son Scot, president at Pepper Construction, as well as the entire construction team in attendance. Jabari, Zari and the rest of the pride had returned home from Kansas by then.

The Pepper Wildlife Center name will stay with the building in perpetuity, just like at other Chicago institutions such as the Field Museum.

The real legacy of Richard and Roxy Pepper’s generosity arrived at the zoo March 15 when Zari delivered the first new cub to be born at the center, a male African lion named Pilipili, which is Swahili for pepper. Though he’s not yet a year old, he has already grown up enough to test his jumping skills between the rocks and the climbing trees.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment