It’s somewhat fitting that the much-needed renovation and expansion of Manhattan’s Jacob K. Javits Convention Center will take longer to complete than its original design and construction. The work has long been subject to political squabbles, financing dilemmas, redesigns and other disruptions.

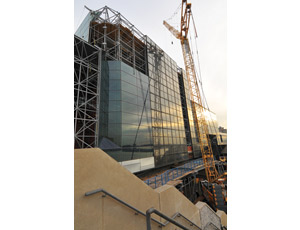

Still, when the $463-million modernization finishes in 2013, the vital meeting hub will be in its best shape ever, thanks to a new 6.75-acre green roof, a high-performance curtainwall, upgraded building and MEP systems, and other improvements heralding its reincarnation as a LEED Silver facility. The center also will have stayed open for business the entire time.

The 25-year-old facility has come a long way, says Barbara Lampen, president of the New York Convention Center Development Corporation, which is overseeing reinvention of a facility first designed by Pei Cobb Freed & Partners. “The building has had such a bundle of issues,” she says.

Even when the Javits opened in 1986, it suffered cost and construction problems, some caused by changes to the “very sound and intelligently done” initial concept, says Bruce Fowle, founding principal of FXFOWLE, the design architect partnering in a joint venture on the project with Chicago-based design firm Epstein. “A lot of the original vision was not fulfilled,” he adds.

Fowle contends that the issues contributed to the center’s leaking roof and facade, and a darker-than-intended curtainwall, which over time merged with problems such as aging mechanical systems and 50 loading docks built for yesterday’s smaller trucks. Given that today the venue annually hosts 3.5 million visitors, 80 major trade shows and 70 big events in its 760,000 sq ft of exhibition space, the need for a fix became critical.

The rehabilitation’s path was characteristically grueling, starting with a 2004 authorization from state officials to fund the job through a hotel room surcharge combined with state and city resources. That underpinned an initial $1.7-billion plan of upgrades and 1.4 million sq ft of new space, though the scope and cost estimates soon grew—indeed, by some accounts they more than doubled.

Then, the 2008 financial crash led to the city and state abandoning their commitments. “We decided we would tackle what we could with the money we had on hand from the hotel tax,” Lampen says.

A downsized renovation and an expansion to 40th Street began in March 2009. While humbler than once imagined, Lampen says the redone center nevertheless will anchor the new Hudson Yards neighborhood that city planners envision, ushered in by the No. 7 subway line extension and zoning changes allowing residential and commercial skyscrapers.

Open House

The project’s organizing principle is simple: avoid disturbing the center’s events. That has colored every facet of logistics, from early focus on the expansion—now key swing space—to a schedule with nine phases of interior renovation on each of the center’s 90-ft bays, overlapping with nine phases to replace 3,800 curtainwall panels and 2,400 skylights; five phases for roof and utilities replacement; and separate phases to remake the Crystal Palace and River Pavilion spaces.

“The economic impact of this business on New York is profound,” Lampen says.

That resulted in extensive overhead protection and scaffolding to allow work during events, features comprising about 10% of the total budget.

Lampen says Tishman Construction, the construction manager, landed “some very good buys” in the down economy, especially when procuring the 110,000-sq-ft pre-engineered CECO building that became permanent expansion space upon installation last June.

The heart of the interior renovation is a 25-ft-high platform supporting 300 pounds per sq foot, with lighting, sprinklers and building systems suspended below it to let shows go on underneath. Meanwhile, crews on the deck above are busy replacing the skylights and curtainwall, painting the structural frame and installing new life safety systems, says Glen Johnson, Tishman’s project director.

Atop the massive deck is a materials hoist and a “forest of scaffolding,” giving crews access to perimeter walls and the 11 stepped 90- x 90-ft “cubes” that reach as high as 185 feet to form the Crystal Palace atrium.

Johnson says the platform went up largely in a pair of two-week windows where the team got full access to the space last summer, and scaffolding is nearly complete, even though activities are limited during events.

“The ebb and flow of the facility is like a circus,” he says, describing a few days of set-up, a few for the event and several breakdown days. “It’s a lot of coordinating around the shows.”

Green Acres

Another major focus is replacing the run-down 12-acre roof and its 93 HVAC, electrical or gas units, each weighing around 20,000 lbs, Johnson says. The preparation included rerouting surface conduit to hang just below the roof, but the linchpin was installing 1,000 feet of 10-ft-wide track for carts to ferry the units along a north-south “haul road” and complementary east-west sections of track for a gantry crane set-up.

Article toolbar

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment