In The Existential Pleasures of Engineering, a book I wrote in 1976, I suggested that the years between 1850 and 1950 might well be called the Golden Age of Engineering.

Before 1850 there had been many important inventions and technological achievements but few schools and societies that are key elements today of engineering professionalism.

In 1852 the American Society of Civil Engineers was founded, just one indication of the spectacular advances to be made in the century ahead in machinery, transport, electricity, chemistry and communications—a golden age indeed.

But after 1950, I feared that engineering was entering into a dark age of public criticism and self-doubt.

For a specific date of gathering gloom I chose January 31, 1950—the day President Truman announced that work would begin on development of the hydrogen bomb.

This event prompted Albert Einstein to predict that "in the end there beckons, more and more clearly, general annihilation." And this was not all the bad news.

Even if we managed to escape nuclear holocaust, it suddenly seemed as if our technology might be making the earth uninhabitable. Warnings reverberated throughout Earth Week in 1970, and the late Sen. Vance Hartke (D-Ind.) exclaimed that, "a runaway technology, whose only law is profit, has for years poisoned our air, ravaged our soil, stripped our forests bare, and corrupted our water resources."

But wait. All was not lost. Even as pessimism seemed about to take over, a new wave of hope for the future arrived in the form of the computer.

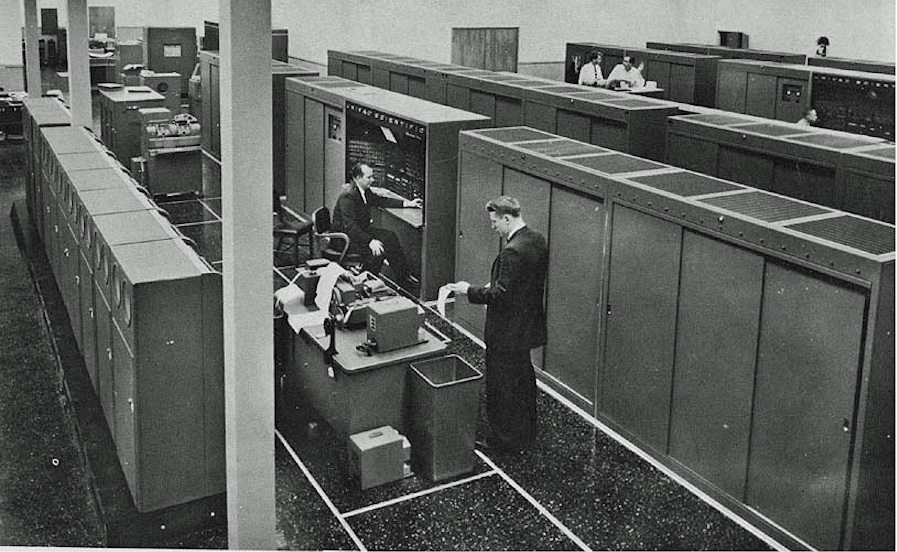

In 1964, when I was doing construction work in the Federal Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair, we prepared a room for a magical machine, the Univac. This wonderful contraption was certainly impressive, although its 5,000 heat-producing vacuum tubes—for which we constructed a special air conditioning system—seemed to remove it from any possible use by the masses.

We never dreamed about what was coming. By 1980 the vacuum tubes were a thing of the past. The transistor had taken over, a million personal computers were on the market, and the world had changed.

Where are the Important Inventions?

So I prepared to rejoin the optimists. But still I wondered. Has our march into the future resumed with zest and increasing benefits for humankind?

Paul Krugman, Nobel Prize-winning economist and op-ed columnist for the New York Times has recently expressed doubts.

"The truth is," he states, "that if you step back from the headlines about the latest gadget, it becomes obvious that we've made much less progress since 1970—and experienced much less alteration in the fundamentals of life—than almost anyone expected."

Krugman has been impressed by a recently published book—The Rise and Fall of American Growth, by economist historian Robert J. Gordon—which argues that achievements in information and communication technology are not nearly as important as the Great Inventions that powered economic growth back in the wonder century (which he identifies as 1870 to 1970, 20 years later than mine).

These Great Inventions extended life expectancy and changed the quality of life—health, safety, sanitation, working conditions, comfort, mobility, communications—in the most basic ways. Dipping into Gordon's book I find that, as he sees it, recent economic growth—since 1970—"has been simultaneously dazzling and disappointing," having to do with entertainment, communications, and the collection and processing of information. The 100-year post-1870 economic revolution is, he maintains, "unique and impossible to repeat."

These economists are interesting folks, and it appears that Gordon, as well as his admirer Mr. Krugman, has ethical and political ideas that go beyond plain statistics.

For example, Mr. Gordon opines that "any consideration of U.S. economic progress must look beyond innovation" to deal with the "headwinds" blowing against the vessel of progress. "Chief among these headwinds is the rise of inequality that since 1970 has steadily directed an ever larger share of the fruits of the American growth machine to the top of the income distribution."

Economics v. Civil Engineering

As I explore, be it ever so superficially, the field of economics—the academic discipline, the social science—I find that the world out there is very different from my world of civil engineering and building construction.

And yet in the daily newspapers the journalists do their best to bring us all together.

Just a few weeks ago I read a front page article in the New York Times headlined "Hiring Rises: Output Lags. It's a Mystery."

It seems that in the year just ended in March 2016, the number of hours Americans worked rose 1.9%. Good news, except that new data just released shows that the gross domestic product in the first quarter of 2016 was also up 1.9% over the previous year. So, despite constant advances in software, equipment and management practices, we're not getting more efficient.

And just think how disappointing this is compared to earlier times when the figures showed increased efficiency each and every year.

Yet the article ends on a cheerful note by pointing out that several companies are currently hard at work trying to perfect driverless cars. Perhaps today's slow productivity growth is just a down payment on a much brighter future!

Well, I don't know. Should we smile or frown? In construction we benefit from computer-aided design but still confront uncertain markets in steel and concrete. Prefabricated construction? Certainly its time has come. Or has it? And chance—the unknown, the unanticipated?

A Clear Productivity Gain

Ah yes—chance. I remember clearly the one leap in productivity from which I anticipated receiving substantial benefits. It was In the middle 1960s—some 50 years ago—while building an apartment house in Brooklyn.

The interior walls, since time immemorial made of two coats of plaster applied to metal lath, were in this case replaced by the newly accepted product: gypsum board, also known as sheetrock.

Our world then was truly changing. The savings in time were known to be considerable, and we could hardly wait to enjoy the increase in profits that would accrue.

What happened—at least for this one project, however—was that the plasterers, organized by their union leaders into belligerent troops, marched in protest and even resorted to violence.

It was a last gasp for the plastering trade, a fateful event, and fate had sent it my way. Police entered the scene, chaos prevailed, and the resulting extra costs were painful, a lesson in economic planning that I have never forgotten.

I do not mean to belittle the world of economic analysis. The question of technological stagnation is well worth our attention.

I'm somewhat less certain than I once was about defining the Golden Age of Engineering. But this sort of uncertainty helps to keep us alert.

Samuel C. Florman is an American civil engineer, general contractor and author. He is best known for his writings and speeches about engineering, technology and the general culture. His works, including The Existential Pleasures of Engineering and a memoir: Good Guys, Wiseguys, and Putting Up Buildings; a Life in Construction, are being re-released as digital books.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment