With no relief in sight from a Federal Aviation Administration requirement that all drone flights be overseen by licensed drone pilots, a San Francisco-based company that had been developing an autonomous aerial jobsite survey system is adjusting. It is refocusing on automation of material detection in its photo-analysis software. It also is releasing a less expensive and hardier version of its flyer.

Skycatch Inc., which supports drone operators with hardware, software and customer-relationship tools, has so far pulled in $46.67 million from 20 investors through seven rounds of funding, according to Crunchbase, a website that follows startups. Autodesk Inc., San Rafael, Calif., is one recent investor. Carl Bass, Autodesk CEO, notes Skycatch is on major jobs, including a secretive corporate headquarters project in California whose owner is known for demanding innovation and performance. “Project managers look at an aerial survey of the day before [in morning meetings],” Bass says.

A Skycatch user, Tomislav Žigo, director of virtual design and construction for Clayco Construction, St. Louis, is using Skycatch’s Dashboard software to process topographic surveys of the site of a proposed stadium for the St. Louis Rams. Dashboard integrates with the Autodesk 360 suite of products through Autodesk’s application protocol interface, Žigo says.

“We produced contour maps from that survey and shaved off some $50,000 of survey work in that area in a day and a half,” Žigo says. “That in itself is worth buying a unit and flying it.”

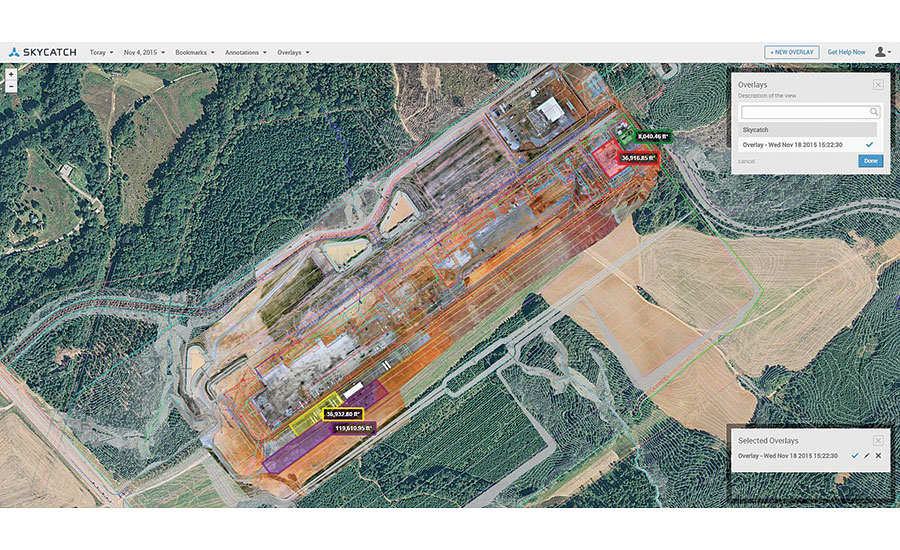

After creating a topographic map, Dashboard lets users measure stockpiles, track changes and annotate and share the maps.

Patrick Stuart, Skycatch’s lead project manager, says his next step is to automate the process. Skycatch is beta testing a program that automatically detects piles of material on a site and measures their volume with 2-centimeter resolution.

“You can classify the pixels and factor in how much air is in a pile, based on the shape of the pile, to get a more accurate measurement,” Stuart adds. He says his developers now are using computer vision to look at the pixels in high resolution and find patterns, to which machine learning is applied to identify the signature patterns of materials commonly found on jobsites. A match can automatically identify the contents of a pile. “Beyond that, it’s just tuning the algorithm,” Stuart says.

He says the team also is working on identifying volume in more difficult cases, such as on varied terrain. “There could be stuff that’s hiding,” he says. For such cases, his team is working on a program that will overlay a scan of the original topography and compare it with a recent scan to find the volumes of changes.

Skycatch plans to release its next drone, the EVO3, in January. With its compression-molded body, it is expected to be less expensive than previous models. Next summer, according to Brandon Montellato, Skycatch’s sales engineer, the company plans to release a more advanced drone called the Explorer 1. Although details are under wraps, Montellato suggests it will go beyond the company’s regular six-month hardware improvements and include updated sensor packages as well.

Although realization of the company’s vision of fully automated drone operations may be delayed by the FAA’s rules, Stuart is not giving up on fielding a system he refers to as “one-touch” for drones to conduct surveys with minimal human intervention. “We’re putting a lot of time and energy into one-touch, on-demand inspection,” says Stuart.

Skycatch’s autonomous UAVs can land on their own at their bases and automatically reload batteries before taking off again—but it is illegal to fly them.

He compares the jobsite to a database, and says the future is using the drone as a device to query it. Instead of walking to far-flung corners of a site, users will touch a point on the site map on an iPad and a drone will automatically fly out, inspect it, shoot video and photos and put them in the cloud. “We can start to consider this as querying a database,” says Stuart.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment