According to a lawsuit filed by the Port of Seattle against Clark Construction, the $1-billion Seattle-Tacoma International Airport International Arrivals Facility (IAF) project didn't turn out the way everyone originally thought during the celebrations marking its opening in May 2022.

The lawsuit, first reported by The Seattle Times, claims that only 16 wide-body airplanes can fit at the new gates supporting the arrivals hall at one time. The project design planned for 20.

The Port of Seattle in a letter says the unexpected capacity issues could lead to "damages to the Port's operations in the tens or hundreds of millions of dollars over the expected life of this project," and gives the airport "an international-flight capacity problem that this project was originally intended to solve."

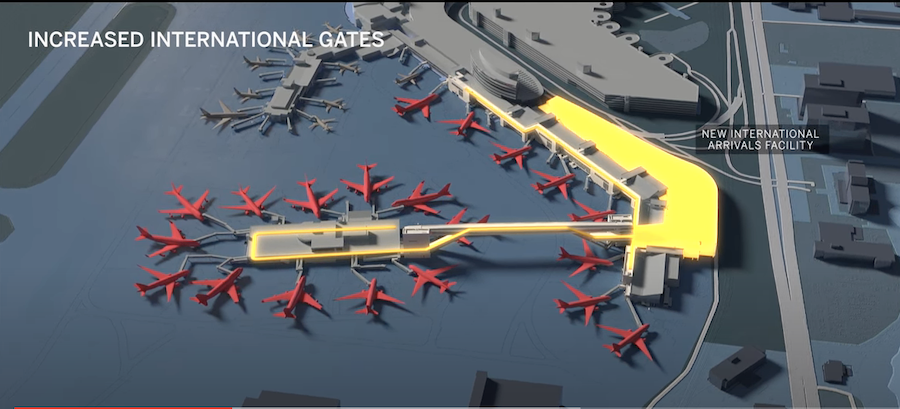

The design of a new secure international corridor along the face of the existing Concourse A was meant to allow eight wide-body aircraft gates direct access to the IAF with dual use for domestic flights, upping the building's flexibility. Combined with the redesigned South Satellite Terminal, the planned 20 gates for large planes at one time could handle any expected influx of international flights.

The lawsuits started with Clark Construction of Maryland suing the Port for more than $60 million plus legal fees in December for costs associated with design changes and pandemic slow downs. The Port countersued in January for $100 million, highlighting the gate design issue.

While Clark served as the lead on the design-build project, Skidmore, Owings & Merrill was the architectural firm on the arrivals hall and Arup served as the designer of the new gates.

“Through a Progressive Design-Build process, Clark, SOM, Arup, and the Port collaboratively designed and built a facility which accommodates 20 wide-body aircraft gates, configured around existing fuel pits and passenger boarding bridges, which was a key directive in the established contractual scope," Arup said in a statement to ENR. "If the Port is seeking additional operational flexibility beyond what was in the contract, we would be happy to jointly explore alternatives with the team.”

Clark says any gate issue is with the Port's original contract, not the design.

"As the design-builder, Clark hired SOM to lead a design team of preeminent, best-in-class aviation design experts to plan and design an International Arrivals Facility that meets the Port's established goals and requirements," Brett Earnest, Clark Construction divisional president, says in a statement provided to ENR. "The current gate configuration is consistent with the Port-approved concourse study and meets the specifications and requirements per our contract. The Port is now identifying modifications to gate design based on operational considerations that were not contemplated in the program requirements in our contract."

In letters obtained by The Seattle Times via a public records request, the Port alerted Clark in August 2021 that four gates—two at the A concourse and two at the South Satellite—couldn't accommodate wide-body aircraft, with one letter saying that "Clark has refused to engage with the Port to identify solutions."

In a statement to ENR, the Port of Seattle says "the Port is active and aggressively working to address deficiencies. Plans have not been finalized."

The gleaming new project replaced a 50-year-old facility with one five times larger at 450,000 sq ft and offers the world's longest aerial walkway over an active taxi lane. The 610-ft-long clear span and 85-ft vertical clearance allows for space for planes to safely taxi under.

To ensure the construction didn’t interfere with airport operations, crews used the Accelerated Bridge Construction method to build the walkway offsite in multiple pieces. With 17 major prefabricated components, the 3,000-ton structure needed seven steel fabricators all within a three-hour radius of the project to create the components. With individual steel pieces weighing up to 170 tons and coming with unique angles, individual welds were up to 6 ft in length and 3.5 in deep. The most complex prefabrication component, the center span, was built off-site on the north end of the airfield, about 2 miles from the bridge location.

The dispute is scheduled for a December trial in King County Superior Court.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment