Climate Pledge Arena

Seattle

BEST PROJECT, SPORTS/ENTERTAINMENT and EXCELLENCE IN SUSTAINABILITY

Submitted By: Thornton Tomasetti Inc.

KEY PLAYERS

Owner: Oak View Group

Lead Design Firm: Populous

General Contractor: Mortenson

Civil Engineer: DCI Engineers

Structural Engineer: Thornton Tomasetti Inc.

Civil Engineer: ME Engineers

Owner’s Rep: CAA ICON

Subcontractors: LeJeune Steel Co.

Approaching Seattle’s Climate Pledge Arena, the appearance of the historic venue seems much the same as it has for the past six decades. The profile of the deceptively squat pyramid and its key elements are exactly the same, although the glow of the new interior shines brightly as you get nearer.

The preservation of the old while also highlinging the new was no accident. The $1.15-billion net-zero transformation of Seattle’s iconic KeyArena into the Climate Pledge Arena involved keeping the original roof and facade. A fitting move for a building that is listed on the Washington Heritage Register as well as the National Register of Historic Places.

As a result, the top-down expansion of the below-grade footprint of the city-owned venue had to be accomplished without disturbing the 45-million-lb landmark lid overhead.

“We took a brittle 1962 concrete and steel roof that had been slightly modified, put it on stilts, excavated 670,000 cubic yards of soil out from under it, upgraded it to modern seismic and built a new arena in a 60-foot-deep hole under an existing roof,” explains Steve Hofmeister, managing principal and structural engineering practice co-leader for Thornton Tomasetti.

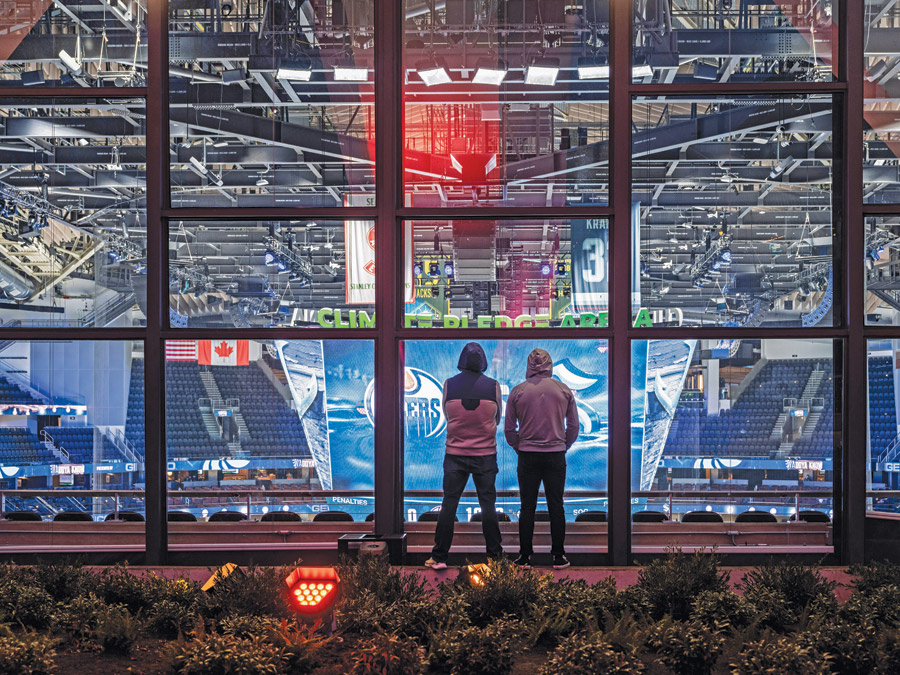

The 28,175 sq ft of digital displays throughout the interior and exterior of the arena create an energizing environment customizable to each event.

Photo courtesy Mortenson/Anna Halstead

Landmark Venue

The original arena was constructed in 1962 for the Seattle World’s Fair and dubbed the Seattle Center Coliseum shortly after. The venue existed with only minor renovations throughout the years until it was transformed into KeyArena in the 1990s with expanded seating and additional capabilities as an entertainment space.

“There was a major innovation in ’96, where they removed the original cable roof and added a hard deck roof,” Hofmeister says. “Sometime between the early ’90s and the early ’60s they deepened the arena bowl.”

Seattle officials announced the planned expansion of the arena in October 2016, and a year later the city council approved a memorandum of understanding with Oak View Group (OVG) to develop it. Construction began in 2018, and the renovated venue debuted in October of last year.

The arena’s 932,000-sq-ft expansion into Climate Pledge Arena not only extends its seating capability to upward of 17,000 for hockey, basketball and touring shows but also makes a sustainable statement about how big capacity spaces can have a greener footprint on communities, explains Populous senior principal and architect Geoff Cheong.

partnership between Oak View Group and the city of Seattle, the project “becomes a model for other owners and developers to consider, to ensure the sports and live entertainment industry continues down a path of more sustainable venues,” he adds.

“For this industry and building type, it represents the highest level of achievement in sustainable design and carbon footprint reduction,” says Cheong. “Not every future venue will end up achieving what was done at Climate Pledge Arena, but we’ve shown that it’s certainly possible.”

More than 680,000 cu yd of dirt was removed during the mass excavation, all of which was hauled out at night between the hours of 7 p.m. and 6 a.m.

Photo courtesy Mortenson/ Alex Fradkin

Rooftop Challenges

The renovation posed challenges that were as difficult as they were unique. Above the arena, a litany of needed retrofits included upgrading the roof rigging for a new scoreboard and bringing the top up to today’s seismic code standards. The old window facade system was carefully removed, taken off site, stripped of contaminates, then reinstalled with its original glass.

“A significant renovation like we were doing requires us to design everything up to the more recent codes, and the seismic codes have gone through such a change over the time,” says Matthew Farber, principal and Kansas City office director for Thornton Tomasetti. He guesses there were upward of 500 structural points that needed to be addressed and upgraded.

“It represents the highest level of achievement in sustainable design and carbon footprint reduction”

—Geoff Cheong, Senior Principal and Architect, Populous

A wooden platform was created under the roof so crews could access certain structural points. Below, crews needed to work around the arena’s old existing Y columns, mandated to be maintained, and 4,000 lb of steel used for the arena’s temporary roof to construct the new arena. Overall, 10,000 tons of steel were needed to secure the structure.

As if the scope of the effort was not enough, the COVID-19 pandemic hit as crews prepared to re-secure the 45-million-lb roof of the original structure onto a new permanent structural steel support. The jobsite had to be closed due to pandemic health safety measures. Only temporary structural elements kept the roof aloft in an earthquake prone area.

At that point “the entire arena was at its most fragile state,” says Mortenson project executive Greg Huber. The project team were forced to wait anxiously until health officials allowed work to resume—one of only three projects in the area allowed to do so during the early stages of the pandemic.

“Unless you were working on a hospital project that was deemed essential to the pandemic, every other project in the state of Washington was shut down,” says Huber. “There was a lot of fear in the construction workforces as well, a lot of people just fearful of the project, taking COVID home to their family or getting COVID themselves.”

Under pressure to deliver the arena in time for the new hockey season, Mortenson worked quickly with its partners to create and implement a COVID response plan that would keep the project moving safely. “We were about half pace for a couple of months,” says Huber, explaining that the project lost around four weeks to the pandemic and therefore had to extend the schedule by two and a half weeks.

“We had plenty of worries when the pandemic hit us,” Huber adds. “It was bad.” But not impossible.

Facing the pandemic, complicated structural challenges and supply disruptions, the project proved to be a heavy lift for all stakeholders involved, says Huber. However, strategy and intensive planning with all subcontractors from the beginning made the arena concept a success.

The 44-million-lb roof structure of the original building was held in place as new supports were built to hold it aloft.

Photo courtesy Mortenson/Alex Fradkin

Collaborative Construction

A CM at-risk project, Cheong says the design team was very intentional about how to preserve the arena’s historic roof and window facade, which was mandated by the city.

“It was through almost five years of collaboration in both design and construction that we were able to develop solutions for an idea as grand and complex as Climate Pledge Arena,” says Cheong. “In order to solve some of the biggest challenges related to the historic preservation and significant excavation of the arena, we utilized new strategies uncommon in arena design.”

The first change to the project came in preconstruction when Skanska Hunt backed out as general contractor and Mortenson stepped in. After Thorton Tomassetti was hired on as a structural consultant to Populous, the teams quickly realized that the project required an integrated approach due to its complexity, explains Farber.

“The schedule challenges, dealing with the existing building, it was very clear to everybody that we had to all get on board and work together to meet that challenge, but everybody was up for it,” he says.

For Mortenson, every part of the Climate Pledge Arena’s construction was a “continued iteration of solutions,” and the team had to quickly solve problems as they arose, says Huber. The team needed to engineer and build a new access ramp down into the arena bowl because they could not use a normal size crane under the roof. Although most of the labor used on the project was based in Seattle, some of the project’s specialty steel supervisors were unable to travel during the pandemic so virtual inspections were utilized. Then there were various shipping delays and supply disruptions caused by the pandemic, Huber says.

“It was everything from rebar to stainless steel to window shades, everything had a different story,” he says, including cooking supplies such as air fryers and hot water heaters. “We had a lot of time where everything was sitting at the port, but no one could unload it. So we had a lot of things to be working around.”

The 932,000-sq-ft expansion increases the seating capacity of the venue to 17,000 people.

Photo courtesy Mortenson/Anna Halstead

The Cutting Edge

Before the temporary steel could be removed, the permanent steel structure had to be in place, Huber explains. The use of BIM helped, he says, turning the construction plan into a visual learning tool that helped inform everyone what materials needed to be ready for the next phase of the project.

“We had to look way down field to make sure that we were understanding where things were at in manufacturing constantly,” he says, which enabled more collaboration. “We had dedicated sessions with our entire project team, every subcontractor, and every two weeks they would do detailed procurement reports. And what they learned is sometimes someone else could get what they couldn’t, and they would help each other out.”

“It was very clear to everybody that we had to all get on board and work together to meet that challenge, but everybody was up for it.”

—Matthew Farber, Principal and Kansas City Office Director, Thornton Tomasetti

all-electric arena is certified net-zero carbon by the International Living Future Institute, promulgator of the Living Building Challenge. The arena utilizes rain water reuse, collecting and disinfecting water to be used as arena ice—with many partners calling it “the greenest ice in the NHL,” says Huber. Gas cooking and heating systems were upgraded to all electric, nearly doubling the arena’s electric service. Solar panels are installed in sections over the roof, and a living wall was installed on the west concourse to provide occupants a restorative space.

“I would love to tell you that we got it figured out,” says Huber, “but all the way through it was super difficult to finish the project because of material lead times and vendors whose manufacturing plants were struggling to make their productions.”

Overall, Huber believes it is the most complex sports arena that Mortenson has ever completed, and getting it right took the cooperation of the entire project team to give Seattle’s hockey team a new home.

“Every day we were working out how to set up solutions so that when we had to go and perform the work, we could do it,” he says. “If we didn’t get the structure right, it’s not just the roof, it’s the people working under the roof as well as what it would do for the city of Seattle. So we had to do it right.”

He adds, “The roof enables the city to have an elite concert venue and gives people a reason to enjoy the area. I think it’s transformational for the city to redefine what that whole area means.”

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment