With apologies to John Denver, West Virginia’s transportation network is much more than country roads. There are also interstates, secondary highways and rural connectors comprising a nearly 39,000-mile road network, 96% of which is maintained by the West Virginia Dept. of Transportation, ENR MidAtlantic’s Owner of the Year.

Although the state’s ubiquitous mountains are scenic, they also present the agency with a host of unusual topographic and geologic construction and maintenance challenges besides normal weathering and wear.

“It’s very, very expensive to do roads in West Virginia,” says state Transportation Secretary Jimmy Wriston, a 26-year agency veteran who was appointed to the top job in October.

West Virginia also has something other states would envy—a $2.8-billion, bond-funded highway and bridge construction program called Roads to Prosperity, which was launched in 2017 with a voter-approved referendum to boost fuel taxes and vehicle fees.

The state’s Roads to Prosperity program helped bridge a $500-million budget deficit.

Photos by Harry Giglio, courtesy Michael Baker International

As of March 2022, WVDOT said nearly 1,100 projects have been completed under Roads to Prosperity, most of which are smaller road and bridge projects in each of West Virginia’s 55 counties. The program has also paid for large projects, such as the $48-million rebuild of a 16-mile stretch of Interstate 64 between Huntington and Charleston; the $37.2-million reconstruction of a nine-mile section of Interstate 77 from the East River Mountain Tunnel to Princeton; the $20-million project to redeck several I-77 bridges in Charleston; and the approximately $70-million effort to pave the final 15-mile section of the upgraded U.S. Route 35 in Putnam and Mason counties.

Wriston says Roads to Prosperity “saved the state” by reversing years of budget deficits and long-deferred maintenance. Where WVDOT in the past faced program cuts to bridge a $500-million budget deficit, “we now have a whirlwind of construction activity eight times bigger than anything we’ve done before,” Wriston says. “And it’s all focused on getting our system back to where it needs to be.”

To successfully implement such a massive construction program, Wriston points to what he feels are other equally important accomplishments of the past several years. Along with legislative approval to expand the use of design-build and other alternative delivery mechanisms, an internal culture change has empowered agency staff to make more timely and informed decisions, he says.

“We now have a whirlwind of construction activity eight times bigger than anything we’ve done before.”

—Jimmy Wriston, West Virginia Transportation Secretary

“Some of our procedures were as outdated as our highways,” Wriston says. Now, asset-management concepts and other data-driven processes “allow us to make good decisions and deal better with utility coordination, right-of-way and environmental issues—things that in the past would have posed roadblocks to getting projects done,” he adds.

WVDOT’s construction activities aren’t limited to the state’s highways. The Rail Authority, which owns most of West Virginia’s short lines, is in the process of replacing the Trout Run Bridge, which was washed out during a major 1985 flood. The new structure will enable the state to extend one of its many popular tourist trains. WVDOT’s Parkways Authority oversees the 88-mile West Virginia Turnpike, a key north-south interstate corridor that Wriston considers “one of the best maintained roadways in the state.”

Roads to Prosperity funds have also helped WVDOT expand its staff, including hiring a record 51 college graduate engineers last year. “We pursue everyone we can and make a career path for them, whether they’re just out of college or someone with many years of experience,” Wriston says.

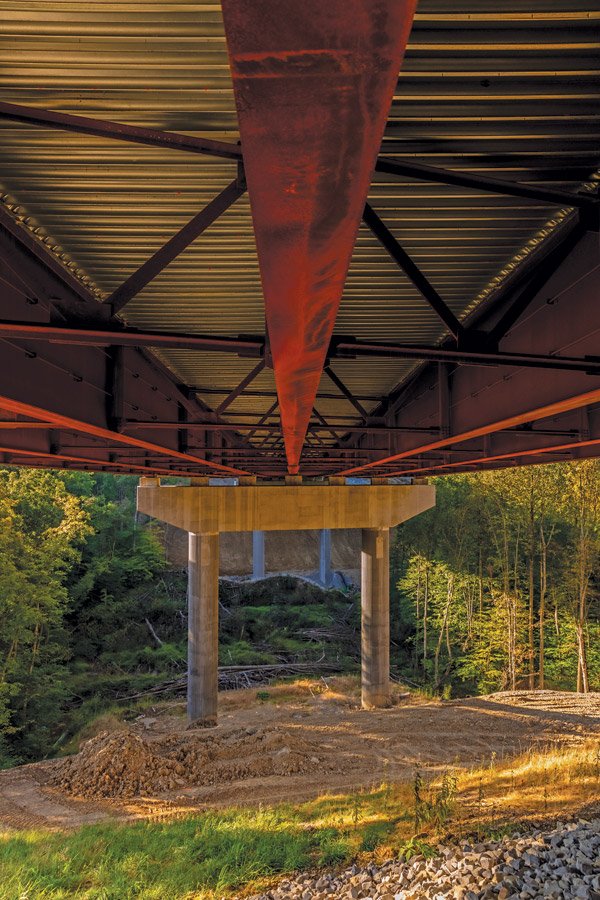

WVDOT’s Corridor H program will eventually create a 132-mile, four-lane highway between central West Virginia and northern Virginia.

Photos by Harry Giglio, courtesy Michael Baker International

Multifaceted responsibilities

These efforts have helped fast-forward the restoration of West Virginia’s transportation infrastructure. WVDOT has plenty of other problems to tackle—from population and tax revenue losses that complicate its ability to satisfy federal matching fund requirements to finding innovative ways to tackle project-specific challenges.

That’s why WVDOT has long viewed its design consultants and contractors as partners and project stakeholders. Since the 1960s, WVDOT’s highway division has worked closely with the Contractors Association of West Virginia (CAWV) via a joint cooperation committee to evaluate trends and agency-proposed changes to specifications for materials and other elements.

“They have always valued the CAWV’s perspective and routinely modify their proposal in order to develop a spec that is in the best interest of the agency, the contracting industry and the taxpayers of West Virginia,” says Mike Clowser, CAWV executive director. “Our members always appreciate the ability to have their opinions considered.”

Collaboration has been critical for the agency’s largest-ever design-build project—Corridor H, which will eventually create a 132-mile, four-lane highway between central West Virginia and northern Virginia.

Other current WVDOT projects include:

I-70 Bridges, Ohio County

Swank Construction is replacing and rehabilitating twenty-six 50- to 60-year-old bridges along the nationally important east-west corridor in West Virginia’s panhandle. The three-year, $214-million project is scheduled to be completed this fall.

I-64 Upgrades, Putnam County

A joint venture of Brayman Construction and Trumbull Construction broke ground in February on a $224.5-million project to widen a 3.8-mile interstate section between Nitro and Scott Depot and upgrade multiple bridges, including a new Kanawha River crossing. Completion is set for summer 2024.

Cheat River Bridge, Parsons

Part of the Corridor H project, the 150-ft-tall, 3,300-ft-long, four-lane structure will be among the state’s longest bridges when it is completed. Triton Construction was awarded the $148-million contract for the project in February.

Approximately 31 miles and an estimated $1.10 billion worth of work remain to complete Corridor H, including a 15.3-mile segment across rugged terrain. Mohiuddin Shaik, vice president and manager of the Charleston, W.Va., office of Michael Baker International, which is serving as program manager/owner’s representative for the project, recalls how WVDOT fostered a collaborative environment from the project’s outset to find opportunities to address technical and cost challenges. By reshaping the project scope and identifying specific tasks that could be more efficiently matched to the most qualified contractors, an expected eight-month procurement process was cut by more than half.

“They recognize the benefits of being proactive and getting input from everyone involved,” Shaik says. “In this case, the approach saves money and gets work done without compromising the quality of the project or the overall schedule.”

The Roads to Prosperity program includes redecking several bridges.

Photos by Harry Giglio, courtesy Michael Baker International

The next horizon

As Roads to Prosperity advances West Virginia’s infrastructure, Wriston expects the recently enacted Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act to have similar long-term benefits.

“It’s a missing piece in funding that I see as being right up there with completion of the interstate system,” Wriston says. He notes that the statute’s qualifications and performance metrics complement those WVDOT already uses, particularly when it comes to tying in with other programs, such as broadband expansion and implementing safety upgrades.

“Rather than getting a paper that winds up on a shelf, we get solutions that can be immediately turned into policies and procedures.”

—Jimmy Wriston, West Virginia Transportation Secretary

To ensure WVDOT stays abreast of innovative transportation technologies and practices, the agency has invested in partnerships with the Appalachian Transportation Institute at Marshall University as well as with engineering programs at West Virginia University and other state schools. Wriston says the agency’s cultural change has led to a “more practical and applicable approach” to research, where ideas are solicited from all levels of the organization. “Rather than getting a paper that winds up on a shelf, we get solutions that can be immediately turned into new policies and procedures,” he says.

WVDOT is also investing in the development of future engineering and construction professionals. The agency updated open-source West Point Bridge Designer software so that it could continue the once national competition on the state level as a means of encouraging interest in science, technology, engineering and math careers among middle-school students.

Michael Baker’s Shaik believes WVDOT’s ability to adapt effectively to opportunities such as Roads to Prosperity and challenges such as the coronavirus pandemic will serve the agency well in the coming years. “Just consider what it took to take on this major road improvement program, then keep it going and deliver projects on schedule with all the pandemic’s disruptions,” he says. “They are very confident in their ability to do whatever is needed to improve infrastructure for the people of West Virginia.”

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment