Public school districts in four southeastern states in recent years spent more per square foot on school buildings using the construction manager at-risk approach than on projects using design-bid-build, say Clemson University researchers in a just-published study of 137 schools.

The study is outlined in an article in the Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, which is published by the American Society of Civil Engineers.

The authors are not sure why school districts in Florida, Georgia, North Carolina and South Carolina are spending more while using CM-at-risk.

But the researchers do note that construction cost growth, as a percentage of what was budgeted or planned, came in lower using CM at-risk, at 0.32%, than using design-bid-build, at 1.25%. Included in the study sample were 85 schools that used design-bid-build and 51 that employed CM-at-risk. CM at-risk, the study authors also wrote, provided surveyed school districts with the sense they are getting higher quality and a better overall experience with the process.

Nevertheless, “Although proponents of CM-at-risk say it has the ability to reduce cost and improve schedule and quality—and theory supports that—in fact, on new public schools, our evidence just does not support that,” says co-author Noel Carpenter, who is also a co-owner of a North Carolina-based mechanical contractor.

Industry officials say the study may provide support for a theory floated by proponents of alternative-project-delivery methods—namely, that savings in cost and schedule—and the certainty and trust engendered by more-collaborative building methods—triggers owners and their contractors to plow money saved or not used to cover cost overruns back into better-equipped science labs, more-comfortable gym locker rooms or more-resilient roofing membranes.

And while these expenditures may push the first costs higher and show up in studies as higher per-square-meter completion costs, the spending may deliver greater value in the long run.

But the newly published study was not designed to produce data on that specific issue, Carpenter said.

A forthcoming study from the same authors is set to delve deeper into perception, experience and actual costs of CM at-risk. It will show that school-district construction managers who used the approach are satisfied with it.

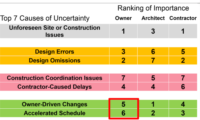

Other, earlier studies of project delivery methods have run into problems separating owner-initiated scope increases, either made before or during a project, from other forms of cost growth, such as unexpected cost overruns beyond initial contractor estimates or price guarantees.

Building Construction Puzzle Pieces

Nevertheless, the new research adds a potentially important piece to the evolving picture of alternative project delivery and how it is used and perceived. Clarifying that picture is important as industry associations engage in state-level lobbying to rewrite laws to allow more public-works agencies to use alternatives to design-bid-build.

The article grew out of research submitted by Carpenter as part of his 2014 PhD dissertation at Clemson. His co-author is Dennis C. Bausman, a faculty member in the school's construction science program.

Alert to the controversy that sometimes arises during discussions of different project delivery methods, Carpenter said in an interview, "It's important to me that you know that we’re not on a side or team and don’t care who wins. There’s nothing to be gained for me."

“We don’t want to be perceived as people who are attacking or tearing down” one project delivery method or another, he added.

Chosen from a pool of more than 830 projects, the 137 selected for study from the four states were picked based on availability of data and the school districts' willingness to participate.

According to the authors, design-bid-build “was significantly superior” to CM at-risk when it came to costs across all metrics. That seems especially true when measured as cost per square foot: CM-at-risk rang up at $192 and design-bid-build at $149, a difference of about 29%. Further, in cost per student, CM at-risk was $27,057.00, and design-bid-build was $20,915.60.

Taking into account all cost metrics, design-bid-build won, the authors wrote, but they also made an emphatic disclaimer that cost performance is not necessarily an indication of project value and doesn’t account for life-cycle savings. Enhancements made to projects with savings “don’t necessarily get accounted for as savings,” Carpenter observed. The money may be reinvested to improve furniture or make another upgrade, he said.

CM at-risk makes the project schedule more predictable, the journal article stated, but the data from the study “indicated no significant schedule performance difference under either delivery method.”

Surveys of the school district construction managers conclusively demonstrated higher satisfaction with product and service quality under CM at-risk.

Response to Construction Management Study

The Construction Management Association of America, which represents construction managers and lobbies for greater contracting flexibility, had a mixed response to the journal article, calling it a needed step in information gathering in a field in which hard data is sparse. “The authors should be credited with taking on an important subject,” said CMAA Senior Vice President John McKeon.

But he questioned the conclusion that CM-at-risk is more costly when the data in the study on cost growth showed CM at-risk to be superior. And he wondered about some of the terminology and assumptions.

In particular, McKeon said the journal article failed to distinguish adequately whether owner-initiated scope increases had added to the project cost.

To meet the definition of CM at-risk, McKeon cautioned, CM involvement must begin early enough to provide meaningful preconstruction services. Otherwise, ”it’s not CM at-risk,” he notes. And in instances in which the design-bid-build method was used, yet owners adopted prequalification, prototype designs and other elements of CM at-risk, “can you still call it traditional design-bid-build?” McKeon asked.

In Carpenter's dissertation text and during an interview, he reemphasized that there is no conclusive evidence to support the superiority of either delivery method in terms of cost and schedule growth, claims, and callback performance.

Further, Carpenter made it clear that he remains neutral on project delivery selection and that “decision-makers must determine which criteria are most important for their districts” in making a choice.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment