Controversial changes to the U.S. Clean Air Act just proposed by the Environmental Protection Agency are still years away from being finalized and may ultimately be decided in federal court.

After months of delays, EPA on June 13 unveiled long-anticipated changes to its New Source  Review (NSR) rules that it claims will make it easier for utilities and manufacturers to repair, upgrade and expand powerplants and industrial facilities. EPA contends that the relaxed NSR rules-some of which must still be written-will lead to more work for design and construction firms that do environmental work at powerplants and factories. But some say that, with relaxed rules, there will be fewer modifications.

Review (NSR) rules that it claims will make it easier for utilities and manufacturers to repair, upgrade and expand powerplants and industrial facilities. EPA contends that the relaxed NSR rules-some of which must still be written-will lead to more work for design and construction firms that do environmental work at powerplants and factories. But some say that, with relaxed rules, there will be fewer modifications.

The NSR program requires utilities and other industries to install the best available technology when a major plant modification or routine maintenance increases air pollution. A central issue has been how large a modification triggers the technology requirement and what is the definition of "routine maintenance." The current NSR program contains "regulatory roadblocks," admits EPA Administrator Christine Todd Whitman.

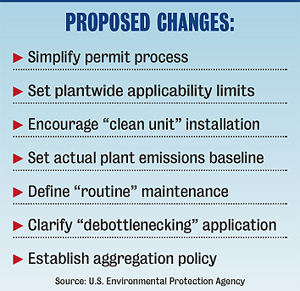

Under the new plan, EPA will finalize four provisions that were first proposed in 1996 and craft three new reforms. The 1996 provisions include creating a simplified process for companies that undertake environmentally beneficial projects, and a site-wide emissions cap program that will allow flexibility for a facility to modernize without increasing air pollution overall. EPA also will give plants that install "clean units" operational flexibility if they continue to operate those plants within permitted limits

|

| GREENER? Opponents claim changes would gut clean air laws. (Photo courtesy of American Electric Power) |

The three new proposals will go through a standard rulemaking process and public comment period. That could take anywhere from 18 months to three years to become law, says Whitman. The most controversial reform will be defining routine maintenance, repair and replacement. At present, NSR excludes activities that are "routine," but a complex analysis must be used to determine what repairs meet that standard. EPA also will propose a rule to clarify how NSR applies when a company modifies one part of a facility so production can increase in other parts of the same facility. In addition, the plan will also establish criteria for determining when multiple projects implemented in a short duration should be treated separately.

Jeffrey R. Holmstead, EPA's assistant administrator for air and radiation, insists that, when implemented, the proposed changes will "significantly reduce emissions." But he says that EPA has not completed an analysis to provide specific details.

PSEG Power, Newark, N.J., completed upgrades as part of a settlement reached earlier this year with the government. "It is still unclear what changes the administration has in mind for powerplants," a PSEG spokesman says. There will continue to be uncertainty until the rules are final, he adds.

EPA was attacked by lawmakers and by environmental groups even before the changes were unveiled. New York Attorney General Eliot Spitzer, an outspoken opponent to relaxing NSR, promised to sue over the rules, asserting they dismantle the clean air laws. "This decision is a victory for outdated polluting powerplants and a devastating defeat for public health and our environment," said Senate Environment and Public Works Committee Chairman James M. Jeffords (I-Vt.).

The proposal is "designed to pander to special interests," charged Buck Parker, executive director of Earthjustice. But the Electric Reliability Coordinating Council, a group of power generating companies, praised the plan as a step in the right direction.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment