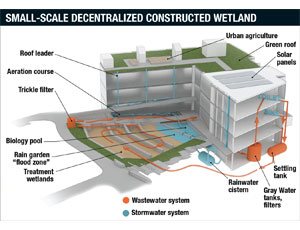

Landscape architects are beginning to collaborate with environmental engineers to focus on natural, decentralized wastewater treatment systems for small and large-scale developments. The on-site systems, which combine landscape design and engineering, typically can reduce potable water use by 50% and discharge into sewers by up to 70%. But even supporters of decentralized constructed wetlands, which have only a backup tie-in to municipal utilities, list several obstacles to their development.

Decentralized constructed wetlands (DCWs) have “huge implications from the standpoint of development in areas of existing infrastructure overcapacity,” said Anthony M. Sease, director of business development for Natural Systems Utilities (NSU), Englewood, N.J., at the 2010 American Society of Landscape Architects Annual Meeting & Expo, which drew a record 5,242 registrants to Washington, D.C., on Sept. 10-13.

But Sease and others pushing sustainable infrastructure, including “green” streets, listed obstacles to widespread development of more nature-friendly systems. Among these are regulatory hurdles, including water-rights issues and building codes that vary from place to place; client and public ignorance; skepticism about long-term viability because of poor-maintenance issues; and higher up-front costs, depending on water rates.

“Some places won’t consider [DCWs],” said Sease, a professional engineer. His company, NSU, formed in 2007, is a utility that designs, builds, operates and owns DCWs.

DCWs are more sustainable than centralized systems because they rely on natural systems and biomimicry; they are local and on-site; and they separate both water and solids and potable and nonpotable water. Furthermore, they reuse, integrate and regenerate water.

The poster child for an urban single-building DCW is the Sidwell Friends Middle School in Washington, D.C. “These need not just be great expanses of grass but can be completely integrated” into a building on a small plot, said Carol Franklin, a principal with Washington, D.C.-based Andropogon. The landscape architect was a member of the school’s design team with Natural Systems International, which engineered the wetland.

Sidwell’s DCW, along with its rooftop solar panels, rooftop urban farm beds and other sustainable features, are being used as educational tools for the students. The DCW, which looks like ordinary landscaped grounds, includes a “biology” pool and a rain garden as part of the building’s stormwater management system, as well as a treatment wetland as part of the wastewater system.

Whether for a single building or an entire community, a must for any DCW is proper operations and maintenance. The most common operational problem is a lack of understanding about the conditions required for efficient biological treatment. “People overload them with too much wastewater,” said one expert. Another said each DCW design must include a requirement for operations and maintenance in the specifications.

Economic viability of DCWs depends on water rates, which vary from locale to locale, said the experts. But centralized systems are economically unsustainable, as evidenced by massive capital needs for maintenance, upgrades and refurbishment. “It’s 100-year-old infrastructure modeled on the Roman paradigm of collection and conveyance,” said Sease.

Another nudge for sustainability, this time from the federal government, is the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Greening America’s Capitals program. On Sept. 8, EPA announced it had selected five capital cities out of 38 candidates that it will help pursue green development. EPA plans to fund teams of urban planners and landscape architects to provide sustainable design assistance in Boston, Jefferson City, Hartford, Charleston and Little Rock.

GAC is a new project of the Partnership for Sustainable Communities, which includes the EPA and the U.S. Depts. of Housing and Urban Development and Transportation. The goal is to coordinate federal housing, transportation and environmental investments; protect public health and the environment; promote equitable development; and help address climate-change challenges.

Another EPA program, started in 2008, focuses on green stormwater management. The goal of the U.S. Green Capitals Program is to revamp parking lots and streets around capitols, including the U.S. Capitol, by adding vegetated bioswales, rain gardens, stormwater planters, vegetated gutters, pervious paving and other “green” systems. “We need to get away from collection and conveyance systems and back to nature,” said Jenny Molloy, a biologist in EPA’s office of wastewater management.

To date, there have been site visits to about 18 cities. Vermont, Connecticut and Virginia have active green infrastructure programs; Maine, Iowa and Kentucky have shown interest. As far as wastewater management goes, “we have not gotten the best outcomes working with engineers,” said Molloy. “We are happy to work with landscape architects.”

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment