Literally miles of pile will be installed in New Orleans over the next two years as the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers rushes to bring the area’s flood-control system to 100-year protection levels by June 1, 2011. As the largest civil-works project in the area’s history, it could be a very loud job. But so far it isn’t, thanks in part to a quiet hydraulic machine that area engineers are making some noise over.

“It's not possible to eliminate all the potential sources of damage on these contracts, but this is one measure,” says Stan Green, program manager for Southeast Louisiana Urban Flood Control Project (SELA). Because much of the work is in close proximity to residences, businesses and infrastructure, the Corps and contractors are specifying pile installation by a special machine produced by Giken America Corp., the U.S. arm of Tokyo-based Giken Seisakusho Co. Ltd.

“The hydraulic press is very quiet compared to vibratory hammers and produces almost no detectable vibration,” Green says. Sensitive wetlands, which often require low vibration levels, are also in the path of some of the projects.

Traditional pile-driving is noisy stuff. “No one knows when we are working, but everyone knows when a vibratory hammer is working on a jobsite,” echoes Mike Carter, Giken regional manager. Handling both sheet and tubular pile, the supplier’s “Silent Piler” generates 50 times less vibration, emitting 75 decibels at 1 meter and 69 dB at 7 m.

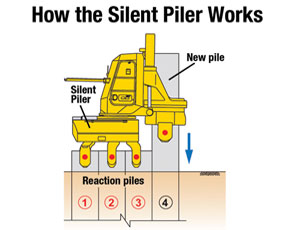

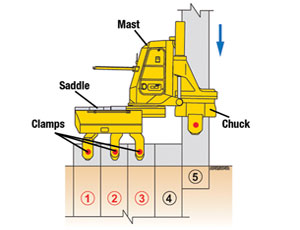

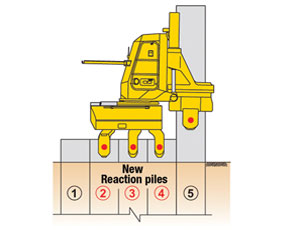

Powered by diesel-over-hydraulic pumps and controlled with a handheld radio remote, the machine is set on a reaction stand. The counterweight is determined by ground conditions and length of piles. Using a hydraulic grapple, the first pile is pressed in, deriving reaction force from the counterweight. As each pile is driven, the machine clamps onto the next, increasing the available reaction force.

After the initial piles are installed, the machine slides off the reaction stand and works from atop the piles. It requires a service crane to feed the piles into position, but the footprint of the actual driving operation is significantly smaller than a traditional hammer, Carter says.

Sources say that Giken is not the only supplier with a hydraulic press-in rig, but for reasons unknown, it is the only one working in the New Orleans area. Giken introduced the method in the U.S. in 2000. Of the 3,200 rigs made at the company’s Kochi, Japan, plant, only six are in the U.S. Four of those are working in New Orleans. The rigs also have been employed on highway projects on the East Coast.

Area engineers began using Giken as early as 2000, while installing drainage box culverts in a dense residential area with high property values. “At the time, the hydraulic press was significantly more expensive than conventional ways of driving sheet pile,” Green says. When it came time to award two more SELA projects, in 2006 and 2007, the method was more cost-competitive in the post-Katrina market of inflated prices.

Blake Andrews, vice president of B&K Construction Co., says he would prefer to use Giken on every job but wouldn’t be able to bid competitively unless it were specified. A typical vibratory hammer costs about $200,000, he adds, compared to the Giken unit, which runs about $1.5 million. Giken can also supply the rigs as a sub and provide its own crew.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment