Despite the continuing uncertainty regarding a long-term federal aviation bill, airport construction programs, especially at the large hubs, are resurging in the U.S. Now flush with profits thanks to burgeoning passenger traffic and low fuel costs, airlines are more willing to contribute to airport infrastructure investments.

“We’ve fully emerged from the recession,” says Christopher Oswald, vice president of safety and regulatory affairs for Airports Council International-North America (ACI-NA). “Air-carrier consolidation has largely played out. From an air service standpoint, we’re at a reasonably stable point in the industry.”

For the longest time, “[major] airports across the country had capital plans ready to go, but they’ve been put on the shelf for the past five to 10 years,” says Perfecto

|

View ENR's 2016 Top Owners Sourcebook |

Solis, former vice president of development and engineering with Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport and now a senior vice president with Parsons Corp. “But, over the past couple of years, the price of fuel has dropped considerably. Now, a lot of airlines are making billions [of dollars], and a lot of airports are now in need of infrastructure improvements. Many have reached the end of their design life. So, airports are taking on those capital pans, but the airlines are also getting more actively engaged.”

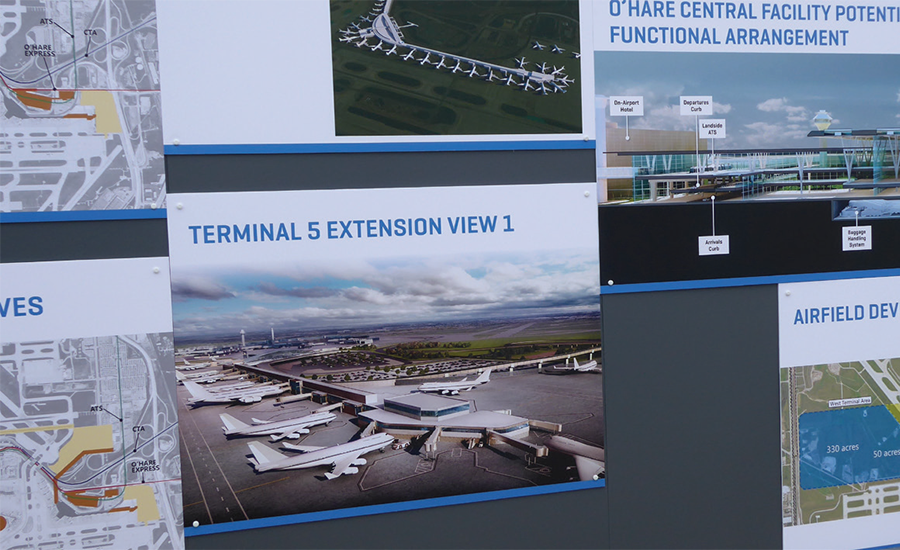

A case in point is Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport, where the previous multibillion-dollar O’Hare Modernization Program now is being replaced by the so-called O’Hare 21 plan.

ACI-NA estimates that U.S. airports have a collective funding need of $75.7 billion from 2015 through 2019, or $15.1 billion per year, to complete necessary infrastructure projects. Commercial airports account for $62.2 billion, or 82.1% of those capital needs; large hubs account for $40.1 billion, or slightly more than half.

Many of the large hubs are repeating a cycle of renewal while planning expansions. “The [O’Hare Modernization Program] is largely behind us,” says Ginger Evans,

Chicago airport commissioner. “Our [terminal] infrastructure is very aged. We’re behind. We underinvested. There were market conditions that made investing difficult in the 2000s, but we’re past that now.”

The city this year announced a new $1.3-billion investment at O’Hare, including a new international runway and other critical airfield projects. American Airlines announced it is adding five more gates at O’Hare—the first gate expansion at the airport since 1993. In July, the city also unveiled a multibillion-dollar long-term plan to add as many as nine new gates to the international terminal and completely revamp Terminal 2.

Airlines are all clamoring for more gate space at the major hubs. “Right now, we’re looking at $10 billion to $15 billion in capital plans over the next 15 to 20 years that will add 35 new gates to Seattle-Tacoma International Airport,” says Elizabeth Leavitt, director of environmental and planning for the Port of Seattle. “We could use eight of these new gates today.”

The airport just last month revealed its design for a $660-million, 450,000-sq-ft international arrivals facility, including a 900-linear-ft aerial walkway that will soar 85 ft over the active airfield. “Our international travel continues to grow at a double-digit pace, but what welcomes international travelers to Sea-Tac is a cramped, 1970s facility that is well beyond its planned peak capacity,” said John Creighton, Port of Seattle Commission president, in a statement.

The description of a “cramped, 1970s facility” applies to many other U.S. airport terminals. “Most of these airports were built in the 1950s to 1970s, at the dawn of the jet age,” says Jarrett Simmons, assistant director of aviation at the Houston Airport System. “At that time, no thought was put into when these buildings needed to be replaced. Now, airports are thinking about how we replace this infrastructure and how we maintain them.”

For smaller and midsize airports that have lost flights due to consolidation, air service is a primary concern, says Oswald. “They have to be more careful about taking on debt or doing capital projects and be more deferential to carriers. Cost control is a really big focus,” he notes.

The consolidation also has affected some large hubs, Oswald adds.

For example, Dulles International Airport lost some traffic to Newark International Airport after the United-Continental merger. “Meanwhile, the smaller National airport is trying to manage growth in a smaller footprint,” says Oswald.

Security, technology and travel trends continue to evolve. Emerging deployment of NextGen flight procedures and associated noise issues will pose challenges, says Oswald.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment