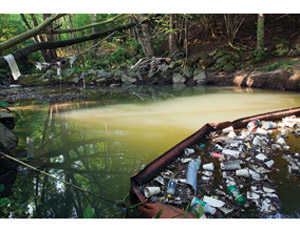

Wastewater utilities, municipalities and states are facing compliance with stringent new requirements for nitrogen, phosphorus and sediment under a strict new “pollution diet” for the Chesapeake Bay watershed.

The “diet,” announced by the Environmental Protection Agency on Dec. 29, is known as the Chesapeake Bay Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL). It establishes a legal framework to ensure that six states and the District of Columbia meet the new requirements established to restore the bay to health by 2025. The jurisdictions affected are Delaware, Maryland, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia and D.C.

Critics charge that bay cleanup has been historically slow and ineffective, and environmental advocates—such as the Chesapeake Bay Foundation—demand EPA develop a TMDL with teeth that forces states to take steps to improve water quality or face penalties.

While environmental groups praised the TMDL, some wastewater utilities worry the plan could disproportionately target stationary sources.

The TMDL calls for a 25% reduction in nitrogen, 24% reduction in phosphorous and a 20% reduction in sediment. The TMDL—which sets bay watershed limits at 185.9 million lb of nitrogen, 12.5 million lb of phosphorus and 6.45 billion lb of sediment per year—is designed to ensure all pollution-control measures to fully restore the bay and its tidal rivers are in place by 2025, with at least 60% of the actions completed by 2017.

The National Association of Clean Water Agencies (NACWA), which represents wastewater utilities, says it is taking a wait-and-see approach to implementation; however, at first glance, the plan seems to disproportionately target point sources, says Adam Krantz, NACWA’s managing director for government and public affairs. Historically, EPA and states have regulated industrial and municipal sources under the Clean Water Act, but they have imposed few requirements on the agricultural community. “Until agriculture is dealt with appropriately, we’re not going to see the type of advances in water quality that we need to remove waters from the impaired list,” he says.

The plan released on Dec. 29 addresses what the agency identified as “deficiencies” in draft plans submitted by the jurisdictions in September.

Among the jurisdictional plan changes are more stringent nitrogen and phosphorous limits at wastewater treatment plants, including those on the James River in Virginia; plans to pursue state legislation to fund wastewater treatment plant upgrades, urban stormwater management and agricultural programs; and plans to implement a new stormwater permit to reduce pollution in Washington, D.C.

EPA says it will oversee each of the jurisdictions’ programs to make sure they implement the pollution-control plans remain on schedule for meeting water- quality goals and achieve their two-year milestones. This oversight will include program review, objecting to permits and targeting compliance and enforcement actions as necessary to meet water-quality goals.

Chesapeake Bay Foundation President William Baker praised EPA for moving forward with “a historic change in how government will restore water quality in local rivers, streams and the Chesapeake Bay.” However, Baker added, EPA should keep jurisdictions’ feet to the fire.

“It is essential that EPA stand firm and impose consequences if the states and the District of Columbia do not achieve the 2009 milestones … by 2011,” he said.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment