With the failed blowout preventer atop BP’s Macondo well removed and BP moving toward a final plugging and abandonment of the well, the industry is beginning to focus more on the causes and eventual outcomes of the April 20 explosion aboard the Deepwater Horizon that led to the deaths of 11 men and months-long oil spill into the Gulf of Mexico.

BP, a joint industry task force and a team of officials from the U.S. Dept. of Interior released three separate reports in the first week of September that give a clearer sense of about the lack of regulations that led to the permitting and operation of the Deepwater Horizon; the technical failures that may have caused the explosion; and the lack of technologies available to respond to the spill.

“This is going to be a dynamic situation for a very long time,” said Michael Bromwich, director of the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation and Enforcement on Sept. 8. “There will be a cascade of reforms,” as the numerous reports into the accident are released.

The most anticipated report was the internal investigation completed by BP over the last four months. The report, released on Sept. 8, points to the explosion being caused by “A complex and interlinked series of mechanical failures, human judgments, engineering design, operational implementation and team interfaces. Multiple companies, work teams and circumstances were involved over time.”

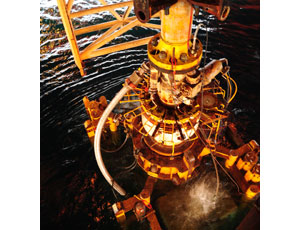

BP said that the cement and shoe-track barriers at the bottom of the well failed; BP and Transocean personnel should not have accepted a test on the well before the mud was displaced; Transocean crew failed to recognize that gas and oil were flowing into the well until it was too late; that once gas reached the rig, it was routed to a mud-gas separator, causing gas to vent directly onto the rig; gas flowed into the engine room and provided a source for ignition; and that gas and fire alarms did not prevent the explosion as they should have. Finally the BOP failed to operate because critical components were not working.

“Based on the report, it would appear unlikely that the well design contributed to the incident, as the investigation found that the hydrocarbons flowed up the production casing through the bottom of the well,” outgoing BP CEO Tony Hayward said in a statement.

Halliburton, which was responsible for the cement job on the well, and Transocean, owners of the Deepwater Horizon, both denounced the report’s findings. A U.S. Coast Guard and BOEM ongoing investigation appears to be focusing on the well design as one of the causes of the blowout.

A separate report released Sept. 8 and conducted by the Department of Interior into the safety and oversight of oil exploration in the Gulf of Mexico points to the former department of Minerals Management Service as not having enough resources to sufficiently regulate the 4,000 rigs in the Gulf. Based, in part, on the 59 recommendations from the investigation, the BOEM is revamping the department, Bromwich says.

“This is not something that is going to be resolved by waving a magic wand,” Dept. of Interior Secretary Ken Salazar said Sept. 8. “It’s obvious we need more resources.”

The investigation into BOEM regulations found that, among other things, managers at the former MMS minimized scientist’s potential environmental impact findings in National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) documents to expedite plan approvals. The report suggests that the BOEM separate the management of environmental functions from those of leasing and development to ensure that environmental concerns are given appropriate weight.

Finally, a third report, released Sept. 7 , from a joint industry task force suggests that oil spill response technology, particularly mechanical recovery methods used in the spills such as skimmers and vacuums, should be improved.

The report includes recommendations for quicker and more effective methods for capping a runaway well, and recommendations for how to better remove oil from the water and keep it from coming ashore.

Andy Radford, a senior policy advisor for the Washington, D.C.-based industry group, the American Petroleum Institute, says that many of the reports and recommendations will lead to long-term changes in offshore construction and engineering. Over time, he says, the industry will likely reconfigure BOPs and rigs to support those devices.

More immediate, though, he says, will be the development of an entire oil spill response industry with new equipment and new vessels devoted to responding to oil spills.

“We’ll have to have all of the equipment ready and never use it,” Radford said. “We will have an industry devoted to the service and maintenance,” of the equipment.

Recommendations from some of the various reports will be worked into new BOEM regulations or legislation, Radford says. On Sept. 8, Salazar said that none of the reports would smooth the way to lift a deepwater drilling moratorium more quickly.

In related news, the BOEM is investigating a Sept. 2 explosion aboard a Mariner Energy oil and gas platform in 340 feet of water, 102 miles offshore Louisiana. Thirteen crewmembers jumped from the platform and were rescued.

BOEM says that the platforms seven wells are secure.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment