Oregon apprentice line worker Jennifer Smith’s recent struggle to receive her journeywoman card has focused attention on a recurring complaint of many tradeswomen around the world. Women interviewed by ENR say the issue goes beyond harassment at worksites. Their complaint: They are being held out of the construction industry.

“Women have remained 2.5% of the construction-trades skilled workforce for the last 30 years,” says Melina Harris, a Carpenter’s Union Local 1797 member in Renton, Wash.

In many places on the West Coast, apprenticeship programs are seeing 12% female enrollment, says Harris, also president of Sisters in the Building Trades (SBT) of Seattle. However, she says, “Retention rates are still minuscule after decades of training women in these jobs.”

Francine Moccio, former director of Cornell University’s Institute for Women and Work, compared the percentage of minority men and women in construction trades in New York and Seattle from the 1960s to 2010. She found the number of minority men varied according to market conditions, but the number of women entering the trades stayed the same.

“I can’t speak for every local in the country, but … the industry [is still] letting in 2% women as a token,” says Moccio. “They’re keeping it to 2%.”

A spokesman for the ironworkers’ union disputed her assertion. He says all of the union’s 150-plus training centers are compliant with Equal Employment Opportunity Commission regulations. Furthermore, the majority of the union’s training centers are required to advertise for apprentices in minority-focused publications, including publications targeting women.

He says one of the union’s members is active on a committee of a womens industry group that looks at ways to increase the number of women in the trades and how to better integrate them on jobsites.

Jim Spellane, spokesman for the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, could not comment on Smith’s case. But he says, “Anecdotally, the numbers of women in the [unions] are up.”

James Boland, president of the Bricklayers and Allied Craftworkers union, said in an e-mail that BAC established a woman’s task force more than a decade ago to “try and understand the obstacles and potential strategies for getting more women interested in our trades.” He claims more women have entered the profession since then but offered no statistics.

No one can say for sure how much sexual harassment limits the number of women in the building trades. Smith, an apprentice line worker in Oregon, filed complaints with the state�s Bureau of Labor & Industries in December 2009 asking the bureau to overturn a local joint apprenticeship training council ruling that she was not ready to graduate as a journey-level linewoman. Smith, who worked for a local utility, claimed gender discrimination and sexual harassment during her apprenticeship was behind her failure to graduate. The apprenticeship council has cited poor monthly progress reports given by Smith�s superiors, but in dramatic testimony in a hearing before the state bureau, Smith has accused one of these superiors of sexual assault.

According to Fiona Shewring, founder of Supporting and Linking Tradeswomen, an advocacy group based in Queensland, Australia, the key is to increase the number of women in trades until they are no longer an anomaly that can be ignored. Shewing, the author of “The Future Is Rosie,” calls this approach a level of “critical mass” that must be reached in order to attain a “shift in culture.”

During the 1970s, the federal government mandated that 6. 9% of work hours be set aside for women on contractors’ federal or federally assisted sites. A December 1980 federal executive order stated, “Affirmative action goals are targets for recruitment and outreach and should be reasonably attainable by means of applying good-faith efforts.”

The standard of compliance is on the basis of good faith, according to the federal regulations. The 6.9% average remains the current goal, but records show it has never been met nationally.

However, there are pockets of growth. Nancy Mason, an electrical workers’ union recruiter in Seattle, says she tallied about 27% women plus 11% minorities in a recent training session.

“There are hardly any women on the jobsites,” says Vanessa Casillas, a union bricklayer from Local 56 in Chicago. “Contractors are using the excuse that there aren’t enough women in the trades to meet the [6.9%] compliance. If that were true, all the unemployed tradeswomen I know of, myself included, would be employed.”

“It’s an outdated goal,” says Patricia Shiu, director of the Office of Federal Contract Compliance in the U.S. Dept. of Labor. “The office of compliance is reevaluating what ‘good-faith effort’ means”. Shiu says it’s going to take another six to nine months to finish reworking the regulations. “In order for the numbers to change, we have to be willing and able to enforce the laws that we implement, and we are,” says Shiu.

“Blue-collar work is excellent,” says Diedra Douglas, a New York Local 18 concrete worker. “The pay is good, and it allows women to support themselves.”

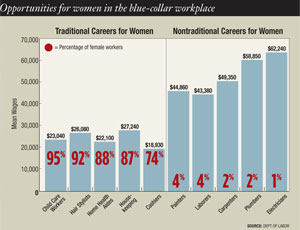

Douglas’ view is supported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which reports that non-traditional careers (carpenters and electricians, for example)...

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment