Although ENR’s cost indexes measure the costs of non-residential buildings, the downturn in the housing market still had a major impact on index movement. During this quarter, lumber prices in the indexes slipped another 0.8% after dropping 27% over the previous five years. Falling lumber prices had been offset by surging steel prices in 2008. However, steel prices were rolled back in 2009 and are just now firming, but with an uncertain future.

As a result, the Building Cost Index (BCI) rose 0.8% this quarter, but the year-to-year escalation in March was just 0.9%, down from 7.3% in 2008 and 4.3% in 2009. The Construction Cost Index (CCI) is less affected by these swings in prices.

The mechanics of what drives ENR’s indexes are explained below.

ENR began systematically reporting materials prices and wages in 1909, but it did not establish the CCI until 1921. The index was designed as a general-purpose tool to chart basic cost trends. It remains today as a weighted aggregate index of the prices of a constant quantity of structural steel, portland cement, lumber and common labor. This package of goods was valued at $100, using 1913 prices.

The original use of common labor in the CCI was intended to reflect wage-rate activity for all construction workers. In the 1930s, however, wage and fringe-benefit rates climbed much faster in percentage terms for common laborers than for skilled tradesmen. In response to this trend, ENR in 1938 introduced its Building Cost Index to weigh the impact of skilled-labor trades on costs.

The BCI labor component is the average union wage rate, plus fringes, for carpenters, bricklayers and ironworkers. The materials component is the same as the CCI. The BCI also represents a hypothetical package of these construction items, valued at $100 in 1913.

Both indexes are designed to indicate basic underlying trends of construction costs in the U.S. Therefore, components are based on construction materials less influenced by local conditions. ENR chose steel, lumber and cement because they have a stable relationship to the nation’s economy as well as playing a predominant role in construction.

As a practical matter, ENR selected these materials because reliable price quotations are promptly available for all three, ensuring the index can be computed swiftly and on a timely basis. While there may be some weaknesses in any index based on a limited number of components, ENR thinks a larger number of elements would increase the time lag between verifying prices and releasing the index. Also, an index made up of fewer components is more sensitive to price changes than one made up of many.

On the downside, the use of just a few cost components makes indexes for individual cities more vulnerable to source changes. These aberrations tend to average out for the 20-city indexes.

Since the indexes are computed with real prices, the proportion a given component has in the index will vary with its relative escalation rate. In the late 1970s, labor’s share of the index dropped because materials prices were in the grip of hyperinflation. For example, in 1979, lumber prices increased 16%, cement prices increased 13%, and steel prices jumped 11%, but common and skilled labor rose 8%. These events resulted in materials gaining a larger percentage of the index.

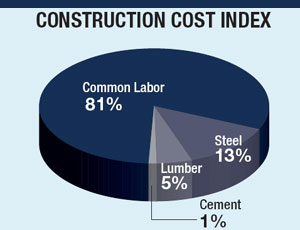

In the original CCI, the components were weighted at 38% for labor, 38% for steel, 17% for lumber and 7% for portland cement. The shifting tide of inflation changed the weight of the CCI components to 81% for labor, 13% for steel, 5% for lumber and 1% for cement. This shift was less dramatic for the BCI, which is now 66% for labor, 23% for steel, 9% for lumber and 2% for cement.

Neither index is adjusted for productivity, managerial efficiency, labor-market conditions, contractor overhead and profit, or other less tangible cost factors. However, the indexes can be used to get a fix on these factors.

During times when productivity is low, the selling price will be relatively higher than the ENR index. At the other extreme, when competition is sharp—such as in a recession—the selling price of finished construction will generally fall below ENR’s indexes.

Post a comment to this article

Report Abusive Comment